Multitask lathes edge in on machining centers

Multitask lathes edge in on machining centers

Like their 5-axis machining center cousins, 5-axis multitask lathes are breaking the traditional part-processing rules and taking manufacturers in bold new directions.

Five-axis machining centers are all the rage these days. Whether used for 3+2 work or 5-axis simultaneous machining, they reduce work in process, improve part quality and enhance flexibility. These machines are so capable that some people in the industry predict that the traditional 3-axis machining centers on which many shops built their businesses will one day be as obsolete as paper tape.

Yet there's more than one way to skin the 5-axis cat: Multitask lathes are able to mill, drill, turn, hob and more, often completing parts in a single setup. Because of these diverse abilities, many shops are re-evaluating their CNC machine tool selection in favor of these supermachines and benefiting greatly because of it. Like their 5-axis machining center cousins, 5-axis multitask lathes are breaking the traditional part-processing rules and taking manufacturers in bold new directions.

Maybe You Can, But Should You?

Suppose your company just bought an Okuma Multus, a Mazak Integrex, a DMG Mori CTX lathe or a similar do-everything-in-one-operation multitask machining center. Provided that the workpiece fits into the work envelope, these high-end mill-turn CNC machines are perfectly capable of milling the complex, free-form part features frequently found on aerospace and medical components that are typically reserved for 5-axis machining centers. They're also darn good at 3+2 milling, able to machine complex valve bodies and similar parts without secondary processing. The decision, however, is whether what remains a lathe at heart is the best place to process such work.

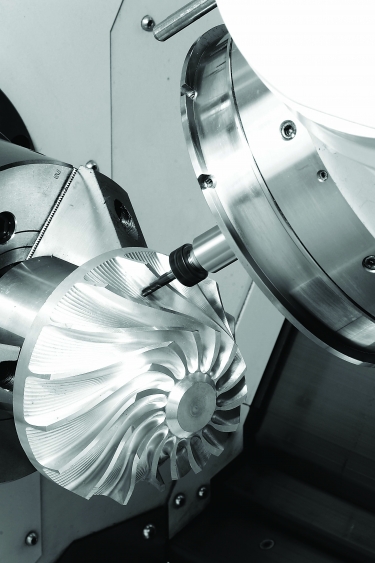

An impeller is machined on an Intergrex multitasker. Image courtesy of Mazak

Chuck Birkle offered a conditional yes. The vice president of sales and marketing at Florence, Ky.-based Mazak Corp. listed a number of applications in which traditional 5-axis machined parts are often more suitable for a multitask lathe than they are for the milling department. These include blades and blisks, propellers, orthopedic components such as knee implants, pump bodies and other "roundish" parts, as well as a few that most people would never guess came off a lathe despite its milling capabilities.

"We worked with a major aircraft manufacturer that was making an aluminum steering component," he said. "The part looks a lot like a turkey wishbone. They were previously producing them on their machining center but were tired of buying and maintaining multiple fixtures and then having to modify them whenever an engineering change came along. So they put it on an Integrex. They now use round aluminum bar stock, remove a very high percentage of the raw material, then snap the completed part off the base and deburr the bottom. Their fixturing is a 3-jaw chuck, and there's just one operation."

Birkle ticked off a number of other parts for which his customers saw significant improvements. One customer reduced lead times on a series of parts for aircraft landing gear from weeks to hours. A pump manufacturer slashed from five to one the number of setups needed to complete a valve body the size of a dinner table. And because multitask machines improve part quality, a leading heavy-equipment engine producer greatly reduced downstream grinding time.

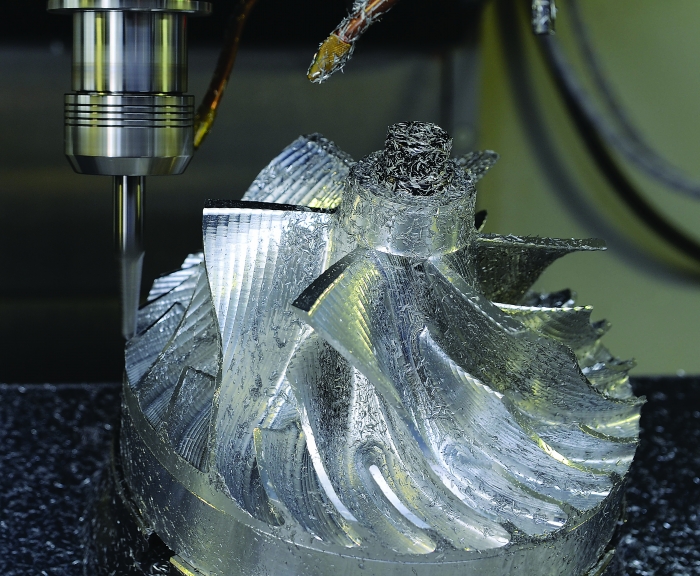

An example of the many parts produced on 5-axis machining centers that would be equally at home on a multitask lathe. Image courtesy of CNC Software

Granted, these parts aren't all 5-axis milling candidates. The fact remains that shops of all sizes are often finding multitask lathes to be a viable alternative to 5-axis machining centers. Birkle listed points that shop management should ask itself before investing in the next machine tool:

- Do we like to be paid morefrequently?

- If scrap occurs, isn't it better to have scrap on the first (and possibly only) operation?

- Do parts travel long distances across the shop floor?

- Are fixture costs killing profits?

- Are specified geometric tolerances difficult to achieve?

- Do we have high amounts of work in process and inventory?

If the answer to any or all of these is yes, a 5-axis mill-turn machine might be for you. "If I was on a

desert island and could pick just one machine to make the parts needed to get off that island, I would choose an Integrex," Birkle said. "There's nothing it can't machine."

Escaping the Island

David Fischer might not agree on the brand of machine, but he would certainly take the same approach as Birkle for getting off the island. A lathe product specialist at Okuma America Corp., Charlotte, N.C., Fischer said 5-axis machining on a multitask lathe offers greater flexibility than a 5-axis machining center.

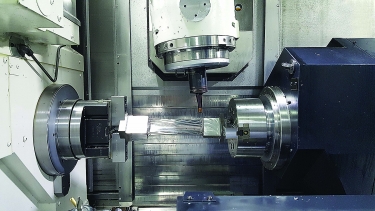

Thanks to their ability to support both ends of long workpieces, multitask lathes are commonly used to machine turbine blades and other rotor components. Image courtesy of Okuma America

"With 5-axis machining centers, you typically need a fairly large work envelope relative to the part size because you're swinging the workpiece around, trying to reach the part with the milling cutter," he said. "That, and the fixturing and sometimes the table can create interference, so you need to lift the part up relatively high or use extended-reach tooling. You don't have these restrictions with a lathe."

On a multitask lathe, the workholder is the chuck. The B-axis movement is achieved by rotating the turret, and the C-axis is the lathe spindle. This construction makes it easier to reach many part features with a milling cutter. Because the part can be held between both spindles or between a spindle and tailstock, its length is less constrained than with a 5-axis machining center.

"This makes it ideal for long parts, like large turbine blades or shafts with complex milling work, which you'd otherwise need a very large machining center to complete," Fischer said.

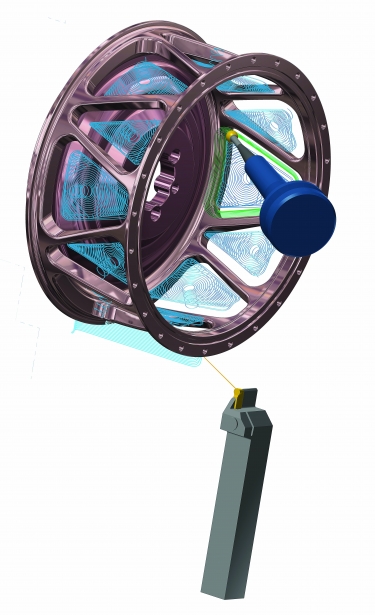

Toolpath simulation is an important step toward collision avoidance. It also gives the programmer an additional opportunity to further optimize the machining process. Image courtesy of CNC Software

Five-axis multitaskers are flexible in other ways as well. They can easily perform milling, turning and almost any other machining operation; in addition, they typically carry large numbers of tools. Therefore, shops can set up a single machine to complete a variety of parts. At worst, the setup time for repeat jobs is as long as it takes to change chuck jaws and call up a program. Rush orders are easily accommodated. Work in process becomes zero, cash flow is improved, and the accuracy of even the most complex part geometries is assured.

Okuma Application Engineer Chris Peluso said skiving and hobbing—two operations traditionally completed on a dedicated machine tool—are easily performed on a 5-axis multitasker. "The tooling looks a little different and acts a little differently, but long shafts with splines on them, for example, are easy to finish in one operation. The same can be said for internal gears that would normally be broached or shaped. Why not set up one machine that can do this rather than invest in specialty machines, especially when you only need to do it occasionally? The tools are all there. There's less part handling. It even uses the same G and M codes, so the programming will be familiar to any CNC lathe operator."

No Big Deal

Ben Mund, senior market analyst at Mastercam CAD/CAM software developer CNC Software Inc., Tolland, Conn., agreed that programming a 5-axis multitask lathe shouldn't be a scary proposition.

"It's virtually identical," he said. "You're using milling toolpaths for the milling portion and turning toolpaths for the turning portion. About the only thing that's different is that there's probably going to be more going at one time with a mill-turn machine. You might have two spindles and two or three turrets working simultaneously, and you need to take the extra step of making sure there won't be any interference. That's why toolpath and machine tool simulation is crucial on a mill-turn."

Skiving, shaping, broaching and more are possible on this 5-axis multitask vertical turret lathe from Okuma. Image courtesy of Okuma America

For those wondering if a new CAM module—or even an entirely new CAM system—will be required after purchasing a multitasking machine, Mund said not necessarily. Shops faced with programming a mill-turn machine can continue to use their machining center module for any milling and their lathe module for turning. They can then merge the two disparate programs by hand.

That approach, however, is probably not going to be as effective as dedicated mill-turn software, which takes care of orchestrating multiple machine axes, synchronizing tool motion and ensuring that the CNC program is as efficient as possible. Having a mill-turn-specific programming package also does the best job of toolpath simulation.

For all their capabilities, Mund said multitask lathes suffer one limitation: The parts machined there should have some sort of an on-axis, generally circular component to them. If not, passing them to the subspindle for completion of the backside may be challenging.

"We're actually doing a test run for a customer on some turbine blades right now," Mund said. "That's a great example of a part that's not a turned part per se but is fairly circular so lends itself well to a mill-turn machine. That said, these machines are just another tool in the toolbox. There are absolutely some parts that fit better on a multitasker, but they're not going to put 5-axis machining centers out of business anytime soon. There are pros and cons to each style of machine. Being successful is a matter of figuring out which one is most suitable for any given application."