Grinding ceramic medical parts requires (diamond) grit, patience

Grinding ceramic medical parts requires (diamond) grit, patience

Grinding ceramics is unlike most other grinding operations. These superhard, brittle materials need a slow and steady hand.

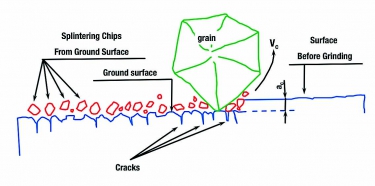

Grinding ceramics is unlike most other grinding operations, wherein a grinding wheel removes material by forming chips—albeit small ones. Grinding these superhard, brittle materials happens via a different mechanism.

"You crack ceramic to death at the surface, and then you clear away that cracked material," said Jeffrey Badger, aka The Grinding Doc, who's based in San Antonio. "That's one unique aspect of grinding it."

In other words, the mechanism of material removal is one of brittle fracture, not ductile flow. However, he added, the cracks must be very shallow to prevent premature part failure.

Frank Gorman concurred that ceramic components can be damaged if they are ground too aggressively. He's the vice president and general manager of Astro Met Inc., Cincinnati, a company that focuses exclusively on parts made from the oxide family of ceramics. These include aluminum oxide (alumina), zirconia oxide (zirconia) and zirconia-toughened alumina (ZTA).

A vibratory bowl feeder transports ceramic pellets, which are used to make radiotracers used in CT scans,

to a Glebar GT-610 infeed/through-feed centerless grinder. Image courtesy of Glebar

"Ceramic is a material that allows itself to be ground only at a certain rate," he said. "This means that you could probably grind it quicker, but if you grind it outside the normally developed parameters for a good-quality part, you're going to potentially put cracks and chips in the material."

Medical Apps

In addition to biocompatible materials, such as stainless steel, titanium and PEEK, parts manufacturers select ceramics to produce medical implants, as well as a host of parts for medical instrumentation and equipment that never enters or touches a body.

Ceramics Grinding Co. Inc. targets the latter, including electrical insulators, said Richard M. Lalli, the company's president. He added that the Maynard, Mass., manufacturer grinds the gamut of ceramic materials, as well as other hard, brittle materials. "We do all of it."

The company's equipment list includes surface, centerless, rotary, ID and OD grinders. "We don't have any CNC machinery," Lalli said. "We're like an old grind shop. We're still using what we were using in the 1970s."

The three-person, 3,600-sq.-ft. shop takes a slow and steady approach to producing its primarily low-volume orders. According to Lalli, the challenges of grinding ceramics are no different from other materials except maybe when it comes to speed. "It's just time-consuming and very tedious."

Because the grinders are manual, Lalli relies on his senses to guide him, such as listening closely to the process and touching a part to feel the level of heat while grinding it.

"Ceramic conducts heat, but it takes a lot of heat. It takes 1,700° C, and you're not able to do that with metals," Lalli said, adding that he has been grinding ceramics for 40 years. "I know when I start grinding how fast I should be going with the speeds."

Besides alumina and zirconia, silicon nitride is a frequently ground ceramic for medical uses. All are attractive materials for implants because they are highly resistant to wear and corrosion and are biocompatible.

"The ceramic materials are very dense, and there is no porosity associated with them," Gorman said. He added that Astro Met customers often select alumina and zirconia for medical implants because they are quite chemically inert. "The reactivity is minimal or nonexistent in most cases, except when exposed to very harsh chemicals, like hydrofluoric acid, and things you normally don't run across in the medical arena."

A selection of ceramic medical parts produced by Astro Met. Image courtesy of Astro Met

These types of ceramics are also selected for medical uses, such as bearings and couplings, because of their tribological properties that minimize wear and friction, Gorman said. After finish grinding, medical components are often lapped and polished to impart a surface finish finer than 1 µin. Ra.

In addition, he said the ceramics Astro Met works with for the medical industry have a high level of purity—at least 99.8 percent. One material developed specifically for the medical industry is 99.95 percent pure. "Because the medical industry, of course, wants the purest and the strongest material."

Hard-Fired

Once a ceramic material is fired, it becomes superhard. For example, zirconia has a hardness of about 1,400 HV and alumina has a hardness of about 2,000 HV, according to Gorman.

"If you look at the more general geological scale (Moh hardness) of 1 to 10, with diamond being 10 and talc being 1, these oxide ceramics are typically up around 8 or 9," he said. "Diamond is really the only material that will abrade them in a satisfactory manner for finish machining."

When grinding hard ceramics, the most appropriate diamond crystals have a high level of friability, said David Spelbrink, vice president of Lieber & Solow Co., New York, a supplier of natural industrial diamond stones and a producer and micronizer of diamond powders and grits through the LANDS Superabrasives division. More friable, or "softer," diamonds have the ability to microfracture and self-sharpen to expose new, sharp cutting edges. "We tend to say that diamond that isn't very tough is friable."

Once diamond grits on a grinding wheel initially create small cracks in a ceramic material,

subsequent diamond grits the material. Image courtesy of Jeffrey Badger, aka The Grinding Doc

The more friable a diamond is, the more free cutting it is, enabling a wheel with those types of diamonds to remove material at a relatively quick rate, Spelbrink added.

"Since all grinding is essentially scratching, it's important to recognize this when it comes to applications where surface finish is crucial," he said. "A more friable crystal should have a sharper point of contact, which tends to lead to smaller scratches, and, since it's generally considered softer, it should be move forgiving. There should also be less heat generation, which will be beneficial for surface finish as well."

The drawback is seen in a grinding wheel with friable diamond crystals, which has a shorter life than a wheel with tougher crystals, according to Spelbrink.

Because chips are likelier to form when grinding silicon nitride than when grinding alumina- and zirconia-based ceramics, which are more powdery, Spelbrink said diamond crystals that are too tough will dig into silicon nitride and produce big chips. "A softer diamond is much more forgiving. A more forgiving crystal gives people a little leeway as to what the surface finish may look like."

According to Spelbrink, the ideal crystal may very well be a true polycrystalline diamond with a microstructure that enables small pieces of the crystal to break off during grinding to expose new cutting edges. "Pricing on a true polycrystalline diamond could make it costprohibitive."

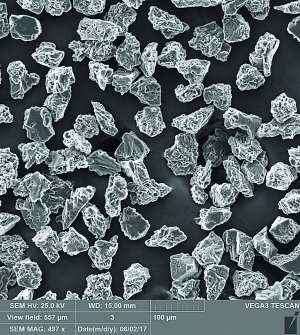

Left: A scanning electronic microscope image of Lieber & Solow's LS050 diamond crystal.

According to the company, it's probably the most friable crystal on the market.

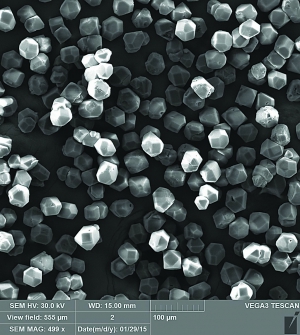

Right: A scanning electronic microscope image of Lieber & Solow's LS4810+ diamond crystals,

which are cubo-octahedral and on the other end of the friability spectrum. Images courtesy of Lieber & Solow

In contrast, he said, a monocrystalline diamond starts with a sharp cutting edge on its side, becoming dull with use. "You would need to put a lot of pressure on that crystal to break it, to macrofracture it. If you have a macrofracture, you would expose a nice, new, sharp edge, but putting a lot of pressure on the wheel obviously has a lot of surface finish implications."

Bonding Together

According to one expert, there is a unique grinding wheel for every different type of ceramic material.

"A crystal that would be appropriate to use in a sintered metal-bond wheel is entirely different than something that would be used in a phenolic or polyamide bond," Spelbrink said. "And an electroplated bond, which is a single-layered bond, would take something different."

While staying in the same general crystal family, softer crystals susceptible to more microfracturing function best in resin-bond systems, he added. Meanwhile, tougher, more macrofracturing crystals are for sintered metal bonds, and blockier crystals are appropriate for electroplated bonds. Grain size and concentration would also vary based on the bond.

The type of grinding machine a wheel goes on also plays a role when successfully grinding ceramic medical parts. One builder of grinders for ceramic applications is Glebar Co., Ramsey, N.J. For ceramics, the company offers infeed and through-feed grinders, said Sean Riess, technical and machine tool sales manager. A through-feed machine removes material from a part's OD, while infeeding is used to form intricate shapes, such as radii, steps and angles on the OD.

According to Riess, a robust spindle is critical to effectively grind ceramics. Additional requirements include precise slide movements to control diameter size, feedback to the machine to auto-compensate and measure diameters, and a stable, rigid machine base to absorb grinding pressures.

"Today, we grind on CNC machines," he said, "because there have been great advances in wheel technology, so you have to have a bit more rigid design and more accurate positioning with grinding and dressing."

Riess added that applying the proper coolant is necessary to prevent the diamond wheels from loading. A high volume of water-based coolant may do the trick. However, the biggest concern is removing heat from the ceramic workpiece.

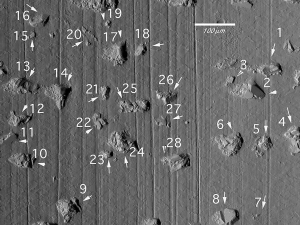

Left: The morphology of grits on a creep-feed grinding wheel in the as-dressed state.

Right: The morphology of grits after grinding 12.95 cm3 specific volume of silicon nitride (Si34).

Image courtesy of Elsevier

"A lot of places just use water with a rust inhibitor," he said. "Soluble coolants have a tendency to load up the wheels."

Similar to other types of machining operations, companies that grind ceramic parts for the medical industry frequently incorporate automation, such as robots and pick-and-place devices, to run lights out. "Medical is always a growing market," Riess said, "and it's always growing with technology and capabilities."

What's changing is part requirements. "Along with that high growth comes the challenge of new, more complex designs and geometries and tighter tolerance requirements," Gorman said. Some dimensional tolerance specs have tightened from ±0.003" to ±0.0003", and surface finish requirements have transitioned from 4 to 8 µin. Ra to 1 to 2 µin. Ra or finer, he noted. "Instead of just Ra, you might see five or six different finish- control parameters."