Turning to improvisation to meet customer needs

Turning to improvisation to meet customer needs

When turning parts, shop improvised to meet customers' needs.n

Making money at a small shop often means taking jobs that do not fit the exact capacity or capability of the available machines. Creativity and adaptation are critical to solving issues that arise when you need to do something with a machine that it was not necessarily intended to do.

At my family's shop, creativity and improvisation were frequently required when operating CNC lathes—more so than other machines. Customers would need help with critical parts, and—feeling obliged to take paying jobs—we would accept their challenging jobs.

Turning centers come in two configurations: bar machines and chucker machines. Chucker machines are designed to have single parts loaded into a chuck, whereas bar machines are set up to make multiple parts from bar stock, eliminating the need to continuously load workpieces. Bar machines are typically outfitted with devices like bar feeders, bar pullers, parts catchers and collet chucks, which enable bar machines to efficiently make parts in a continuous manner.

Creative Cutting

Machines at our shop were purchased as chucker machines, the most common configuration. Our machines had no provisions for doing bar work. However, we often accepted jobs more suitable for bar machines, which forced us to be creative.

These thin shells (inset) were once trimmed by hand, which was unsafe and inaccurate. Welders and machinists at Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems developed a special set of jaws so the parts could be held on a lathe, eliminating hand trimming. All images: C. Tate.

Continuous operation without a machinist present is the primary benefit of running parts from bar stock. As each part's features are machined, the part is parted, or cut off, from the bar. At that point, the bar must be advanced so the next part can be made. Some lathes are fitted with a bar feeder that, when commanded, will drive the bar forward to the correct position so the cycle can run again.

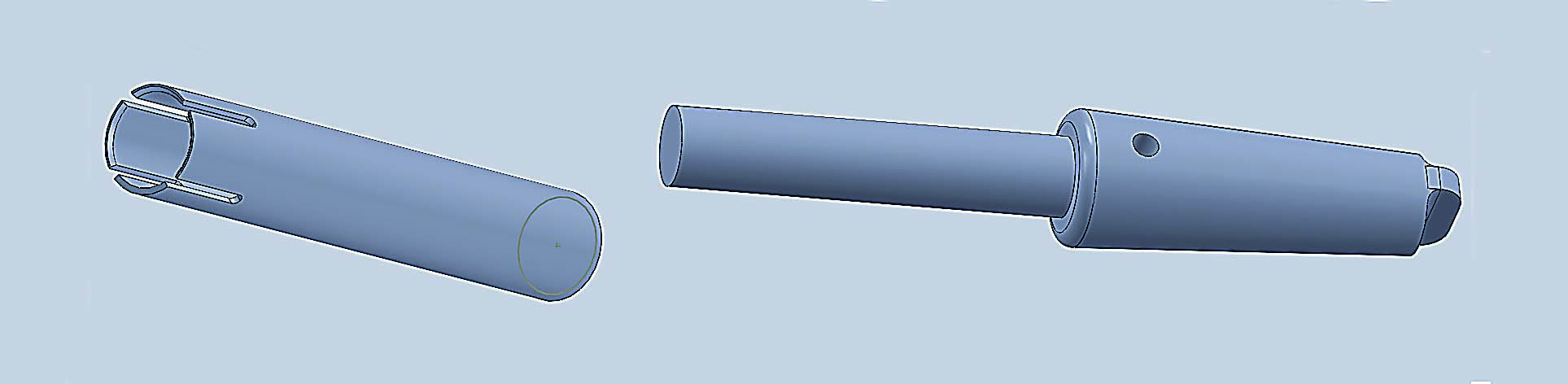

A less expensive and common substitute for a bar feeder is a bar puller. Bar pullers are mounted in a spare tool position and grip the end of the cut bar while the turret pulls the bar into position.

To continuously operate while being frugal, we made our own bar puller. It worked so well pulling became our standard method for bar work.

A bar puller can be easily made from a piece of tool steel by boring a hole the same size as the bar stock so there's a slight interference fit. The depth should be about twice the bore diameter. Turn the OD so the wall thickness is about 0.125" (3.175mm). Next, mill or saw axial grooves in the wall so the puller has four independent "fingers" that can flex as it pushes onto a bar. If the puller is not tight enough, simply bend in the fingers a little to increase the interference between the bar and puller ID.

Whether using a feeder or puller, cutoff parts will fall. Machines are often outfitted with part catchers that retrieve and deposit parts so the machine can continuously run. Not having a part catcher meant parts cut off by our machine would fall into the bottom of the machine, making them subject to loss or damage. We found a simple, effective way to catch parts by placing a plastic bar in the tailstock.

When a part was cut off, the tailstock would move forward and place the plastic in the ID of the part, catch it after cutoff and then retract as the operation continued. While not as efficient as a part catcher installed by the machine tool builder, it was effective. Of course, this method has drawbacks. You can't catch parts that do not have holes, and it is necessary to stop the machine to retrieve the parts.

Casting Ploy

Another trick we learned was how to hold irregularly shaped parts in a 3-jaw chuck. We machined a lot of castings, many of which had features that were best when turned. However, many of these castings were not easily held in chucks or collets because they were asymmetric, unlike the round, hex or square shapes often found in turning operations.

Bar pullers (left) are mounted in a spare tool position and grip the end of the cut bar while the turret pulls the bar into position. This Morse taper adapter (right) fit into a tailstock and held rods, which would catch parts. Rods of varying diameters could be installed and held in place with a setscrew.

The solution was to make a special set of chuck jaws for the 3-jaw chuck. Machining jaws for a CNC lathe is necessary and common at most shops. Most of the time, these jaws are made for round parts by boring or turning on the lathe where the work will be performed.

Many of the castings we machined were not round, so turning a set of jaws on the lathe would not work. To overcome the problem, we built a fixture for the mill that allowed us to machine odd shapes into jaw blanks. After milling, the jaws were installed on the lathe chuck, allowing us to create features that were best made by turning. The only issue with this method comes when runout is critical. Accuracy is lost when the jaws are transferred from a mill to a lathe, so this method may not be suitable for parts with tight runout tolerances.

In ideal situations, a shop will always have the best tools and methods to perform a specific job. However, at many shops, workpieces vary in geometry and size, making flexibility critical to survival. Combine variation and financial constraints, and success often can seem out of reach.

Succeeding in a competitive market requires toolmakers, machinists, shop owners and engineers to be creative and imaginative. I have found that taking advantage of trade shows, joining industrial organizations, touring other facilities and reading trade literature are some of the best ways to get the creative juices flowing.

Most importantly, encourage the people at your shop to be creative and try new ideas without fear of failure.