Small shops warm up to work cells

Small shops warm up to work cells

As automation becomes more flexible and less expensive, work cells are propagating at smaller shops.

At IMTS 2004, the president of a suburban Minneapolis job shop was captivated by the sight of shiny, compact industrial robots as they repeated their movements with ballet-like precision.

"I remember going to IMTS and watching the robots—as everyone likes to do—and thinking, 'These are neat—where could I use them?'" recalled Mike Van Essen, president of Unity Precision Manufacturing, Dayton, Minn.

Unity, a manufacturer with 43 employees, runs CNC mills, lathes, wire EDMs and Swiss-style turning machines. Van Essen said 80 to 90 percent of its business is medical instruments and implants. Because the company does many short-run jobs, some of its fellow suppliers were surprised by its early embrace of automated work cells.

"Most everybody agrees work cells are a no-brainer if it's for a high-volume operation that's going to go on forever with little or no variation," he said. "It's adapting automation to lower-volume work that makes some companies dubious."

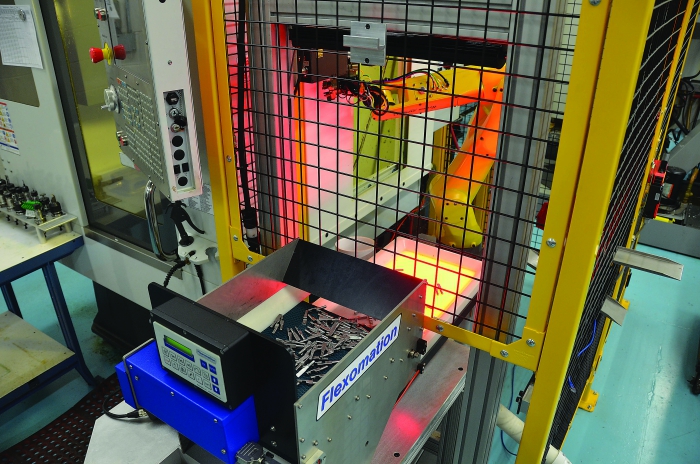

A shaker table shakes small workpieces in front of a vision system at Unity Precision Manufacturing. Once the camera sees that a part is oriented correctly, the robot picks it up and places it into a CNC mill. Image courtesy of Unity Precision Manufacturing.

Those robots at IMTS became the company's first foray into automated work cells. "We started with robot-loaded wire EDMs around 2005," Van Essen said. "I thought about where we had employees performing repetitive tasks. An engineer and I figured out how we could make it work with the EDM, so that's how we started. But part of why it happened was that I really wanted to make it work."

Where it Begins

Van Essen saw the technology and tried to find a way to apply it profitably. More common is a company taking on new work and needing a way to quickly complete it, according to Don Engles, the national sales manager for automation at Productivity Inc., Plymouth, Minn., a FANUC integrator that has helped Unity set up work cells.

"Customers usually want to talk to someone like me because they have a specific job they're bidding or they've won, and they need to start manufacturing. Everything we plan to set up needs to be tailored to that," he said. "But I ask them to also think about what happens after this new job goes away."

The best cell design is one that won't need identical work to stay useful. "Maybe the next job will have the same sequence of operations—for example, grinding or turning, then drilling, then keyways—but needn't be locked into the same specs" as the previous job. It's all about flexibility, he said.

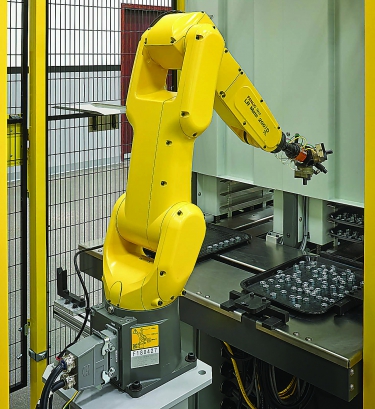

A robot and conveyor system at Unity Precision Manufacturing.

Engles said many first-time customers move into automation in steps. He gave the example of a customer who wanted to automate deburring. The customer was comfortable with automating the first 80 percent of the process and having skilled workers do the rest. "That solution was better for them than trying to go from zero to 100 percent in a single go," Engles observed. "Better to improve what they've got rather than go for the ideal. That keeps the cells simpler and easier to understand, particularly for people for whom this is all new."

Dave Walton heads up proposals at Makino Inc., Mason, Ohio, including conceptualization, design and proposal of automation equipment. He said the company's first-time customers often seek a quick solution for a looming job. "We talk with them about their driving factors, get a good understanding of what they need and then start looking at automation platforms with them," he said. "A lot of times these customers don't understand the long-term benefits they can get from the right automation—they're focused on the immediate task at hand. We can show that a well-designed cell can move them from, say, 60 percent spindle uptime to 95 percent."

Customers need to get through the adjustments that come with the first move from manual to automated operations, Walton noted. Once they do, they tend to find more and more places where automated work cells make sense.

The Automation Mind-Set

"Running an operation manually and running it with automation takes two different mind-sets," Walton said. "Once customers understand that there are practices they need to change to get the most out of automation, they really start to see the benefits. They'll want to do more of it."

In a manual operation, for example, the operator wants to load as many parts as possible on a fixture to keep the CNC machine working as long as possible without stopping. In that way, the operator can walk away from the machine and do other tasks, Walton said.

But with robotic automation, loading up the fixture may not be the best practice, he continued. The robot is always available. Depending on the type of workpiece material, end users can begin to lose the cost benefit of maximizing the number of parts per fixture once they get past the threshold of a certain number of parts. "After a certain point, it doesn't pay to put more parts up at a time. You can reduce your fixturing costs, since you don't need to fixture so many at a time," Walton said. "If the fixture goes down for some reason, there are less parts on it to fail. These are trade-offs to be aware of."

A robotic pick-and-place operation. Image courtesy of Productivity.

Even experienced work cell users continue to find ways to better implement automation—aided by improving technology. At Unity, the most recent improvement was to a simple milling operation. A robot picks up each workpiece and loads it into the machine, saving a worker from having to do so. Unfortunately, Van Essen said, as the cell was originally constituted, human labor was still required to place each workpiece in a tray that was then conveyed to the robot and CNC machine. The tray ensured that each workpiece was oriented correctly so the robot could pick it up and place it in the machine.

"If a person has been spared the task of loading the machine but still needs to carefully place the workpieces in proper orientation onto the conveyor, that's not really an improvement," Van Essen said.

The new system features a custom-made shaker table that orientates workpieces while being viewed by a vision system. Once a workpiece has been shaken into its proper orientation, the camera signals the robot. The part is then picked up and loaded for milling. After the operation, the robot picks up the part, measures it with a laser micrometer and sends it on its way. The entire process is done in 12 seconds, Van Essen said.

Maximizing Assets

Van Essen reiterated the point that his workers are too valuable a resource to nursemaid a single machine. Automation would be less of a driving factor if he could find all of the people he wanted. "It'd be easy to expand if every time you bought a machine, an operator came with it. But that doesn't happen," he said. "So we try think of different ways to get the work done."

This perspective is 180° from the common perception that manufacturers invest in automation to be able to lay off a bunch of expensive workers. "It's not that I want to get rid of people. It's rather that I can't find them and hire them." According to Van Essen, automation frees up the workers he does have so that, in addition to running machines, they can learn to use vision systems or program robots, making them more valuable.

Productivity's Engles agreed. The U.S. has "a critical labor shortage," as well as a high cost-per-hour of labor compared to some rival nations, he said. "If we're going to be more expensive, then we need to be more productive. For example, robotic machine tending can spread your $38-to-$40-per-hour skilled employee costs out over maybe seven to 10 cells rather than one to three. If you can get your $40-per-hour skilled employees to where they're monitoring the processes in eight cells rather than feeding the processes in one or two, that net cost per cell is now $5. At that cost, you can be competitive anywhere in the world."

Now's the Time

For shops that couldn't see how automating work cells could pay off a decade ago, there are good reasons to take another look. If the "stick" is global competition and a labor shortage, the carrot is more-capable equipment at a better price point. Makino's Walton said one of the major ways automation systems have improved is in monitoring and interconnectivity. Remote monitoring can give comfort to shop owners who don't trust lights-out automation, he said. "We have customers who use their cell phones to check up on their work cells over the weekend and get email or text notifications."

Interconnectivity, Big Data and analytics are the most important recent developments, said Productivity's Engles. "I know the robotics group at FANUC is working hard on real-time connectivity with no down time in-plant," he said.

Van Essen noted such new technology tends to get easier to use and less expensive over time. He recalled seeing a then-new vision system at IMTS over a decade ago. At the time, the system cost around $150,000. "I remember seeing it and thinking, 'Well, that'll be nice for Ford or some big OEM but not for us.' Now, however, you can have two conveyors easily set up with vision systems for under $10,000."

Highway vs. City Driving

"Several years ago, we used to do a lot of what I like to call 'highway driving' production," said Brian Halwix, director of team development at New Dimensions Precision Machining, Union, Ill.

The company specializes in the production of hydraulic manifolds and has seen a shift from high-volume work to low-volume runs. "We had vertical machining centers that would run large batches continuously, which allowed us to coast for miles and miles without changing gears. But all that has changed," Halwix said.

A prototype pallet system at New Dimensions features identical tooling, fixtures and control software for the automated cells, allowing program and tool data to be quickly and easily transferred for production. Image courtesy of Makino.

Today, customers do less annual forecasting, they reduce inventory in favor of just-in-time delivery and they do not combine shipments. Customers want parts in small batches. The need for quick turnaround is urgent, and there is continued pressure to keep pricing low.

"Now it's all about 'city driving' production, with many starts and stops. We can only go a few blocks before hitting another traffic light," Halwix said. "In this type of environment, it no longer makes sense to spend a half hour doing setup on a vertical machining center, only to run an hour of production. To be competitive these days, we have to be able to get better city mileage."

The company's road to flexibility began in 2007 when it acquired four Makino a61 horizontal machining centers and an MMC2 automated pallet-handling system that links the HMCs, cell control software and pallet loaders. New Dimensions later added two a61nx machines to that cell.

Today, the company has three flexible manufacturing systems. In addition to the first system, another was created with four a51 HMCs and two a51nx machines. A third cell features six a51nx machines. Within each of the three automated pallet handling systems, the six machines in each cell run parallel processes with five jobs in production at a time. Each cell's jobs are prioritized and coordinated by a Makino MAS-A5 cell controller.

New Dimensions has been able to produce up to 300 percent more parts per spindle than on its previous stand-alone machines, according to Halwix. The company credits the flexibility of these systems for its ability to run 50 pieces quickly while charging per-piece prices that are comparable to what it charged when running 500 to 1,000 pieces.

—M. Anderson