Troubleshooting solid-carbide boring bars requires the right diagnosis

Troubleshooting solid-carbide boring bars requires the right diagnosis

Troubleshooting machining operations can be a daunting task, especially boring operations. This is because when machining the outside of a part, you can see what causes the tool to fail. However, when a tool is buried in a hole, as is the case when boring, you can't see what is happening to the tool.

Troubleshooting machining operations can be a daunting task, especially boring operations. This is because when machining the outside of a part, you can see what causes the tool to fail. However, when a tool is buried in a hole, as is the case when boring, you can't see what is happening to the tool.

If you've done any boring—especially small-hole boring with a solid-carbide bar—you've probably experienced the following: The boring bar is set at or slightly above centerline and is not larger than the hole. The conditions look good. The program checks out. You feel comfortable about the setup and press the start button. Coolant sprays everywhere, and you notice nothing unusual until the boring bar holder retracts from the part.

At that point, your biggest fear has come true—the tip of the boring bar is missing!

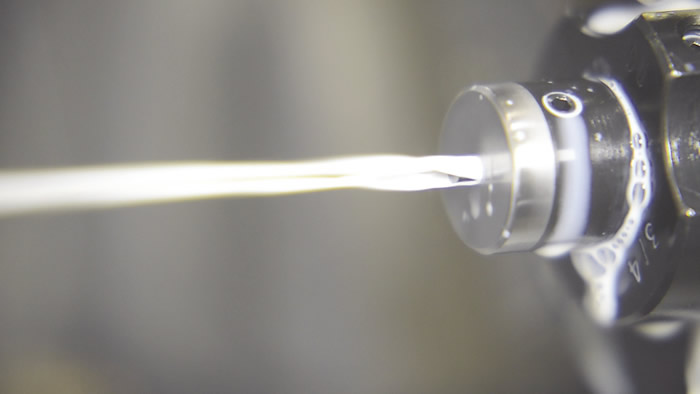

Scientific Cutting Tools is introducing a toolholder with Coolant Ring Technology, which enables coolant to be applied around the circumference of a boring bar. All images courtesy Scientific Cutting Tools.

When this occurs, it is normally because of chip packing or the bar trying to feed past the end of a blind-hole. Upon examination, if the tip of the boring bar is still in the hole and difficult to remove, the hole is most likely packed with chips and you've found the cause of the catastrophic failure. In this case, the cutting parameters, such as DOC and feed rate, created a greater volume of chips than could be evacuated. A solution would be to apply a smaller boring bar, if possible. If not, the cutting parameters must be backed off to create a lower volume of chips.

If the broken bar is not in the hole, or is loose in the hole and being obstructed from exiting the hole, you may have tried to feed the bar deeper than the existing hole in the part. A boring bar does not make a good drill!

Rapid Wear

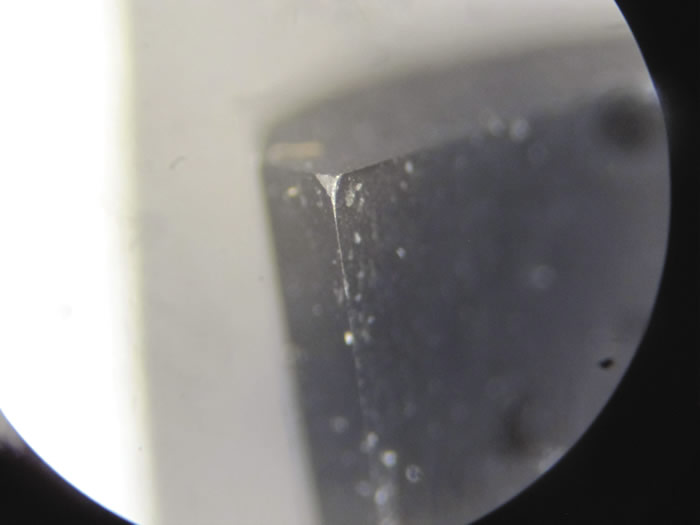

After you've made the adjustments necessary to allow the boring bar to finish holes without suffering catastrophic failure, let's say you decide the production per shift is not acceptable and you feel you're changing boring bars too frequently. Upon examination of the bar, you determine the tool's cutting edge has excessive flank wear (Figure 1).

However, the cause of excessive or rapid flank wear can easily be misdiagnosed. Frequently, over time, interrupted cutting or chatter can cause small pits to form on the cutting edge that resemble flank wear.

Figure 1. The cause of flank wear is easy to misdiagnose when troubleshooting boring bars.

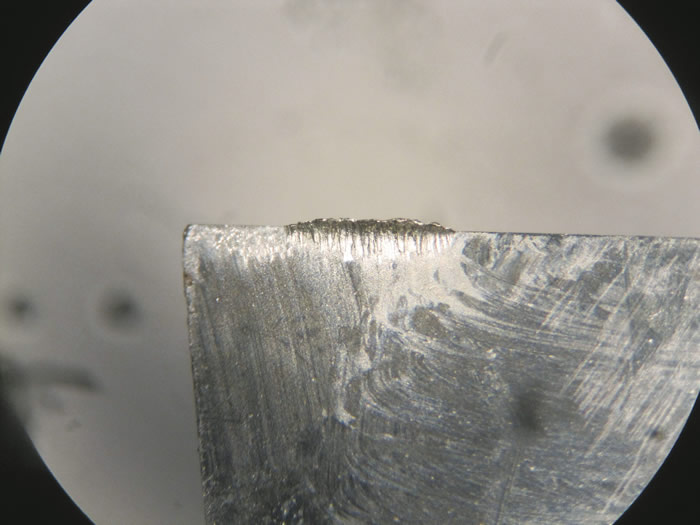

In addition, what looks like flank wear can start as built-up edge on the top surface of the bar (Figure 2). This is caused by metal from the workpiece welding to the top surface at the cutting edge as a result of heat and pressure during chip formation. Then, at some point, a chip will dislodge the buildup, along with a small piece of carbide from the bar.

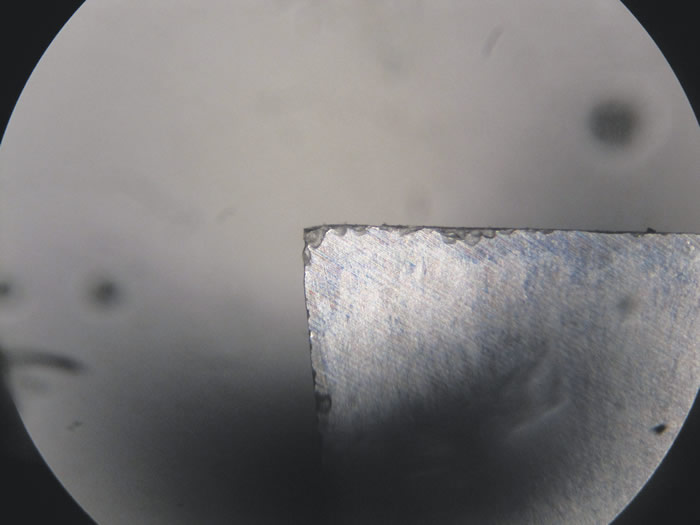

To determine if one of these conditions caused the tool to look as though it has experienced flank wear, bore one or two holes and then check to see if any BUE or chipping exists (Figure 3 below).

To reduce BUE, the pressure or heat must be reduced. Pressure results from an overly high DOC and feed rate. Lowering the cutting parameters will reduce the pressure, as well as the heat, but it also lowers productivity. A more productivity-enhancing change would be to apply a coated tool. Coatings reduce the heat that develops as chips move across the cutting surface. A thin, PVD AlTiN coating should be effective, whereas a CVD coating would be too thick and can cause the cutting edge to deteriorate.

Cool Down

Generally, end users try to reduce heat by applying coolant. This is usually simple when machining an OD but can be difficult when boring a small ID, because the hole is partially filled with the boring bar and hot metal chips that need to be cooled.

A coolant line positioned close to the hole often gets in the way, so the best approach is to supply coolant through the boring bar holder. An ample supply of coolant around the circumference of the bar would be ideal, enabling coolant to find the path of least resistance and access the bottom of the bore. Typically, this requires positioning several coolant lines, such as one on the cutting edge side, one directed at the top of the bar and one on the back opposite the cutting edge.

Figure 2. Built-up edge can be misdiagnosed as flank wear after a chip dislodges the buildup

and pulls a piece of carbide with it.

(In response to the need for ample coolant, Scientific Cutting Tools offers a toolholder with Coolant Ring Technology, which enables coolant to be applied around the circumference of a boring bar. This encompasses the bar in a "tube" of coolant.)

If the tool experiences chipping after boring a couple of parts, the most likely cause is an interruption in the part, such as a cross-hole or keyway. When boring an interruption, you may need to apply a tool whose cutting edge has a corner radius, hone or both a corner radius and hone.

If the chipping is not from an interruption, chatter could be the culprit. Chatter is similar to an interruption in that as the tool flexes, it moves downward, then moves back up as it relaxes, shocking the cutting edge. A possible solution is to increase the feed rate. A 10 percent increase can sufficiently boost the pressure to keep the tool in a deflected state, preventing it from relaxing and experiencing a shock.

Figure 3. An example of a cutting edge with severe chipping.

There is good news if what you diagnose as flank wear actually is flank wear. Numerous studies on the subject have concluded that a small decrease in cutting speed will make a big difference in the number of minutes a tool can remain in the cut before flank wear becomes an issue. For example, a drop in speed from 400 to 300 sfm might extend cutting tool life from 12 to 40 minutes.

Solving production issues always is a high priority and should be handled in a timely manner. But do not be too quick in identifying failure modes. The wrong diagnosis may trigger changes that are counterproductive—or even make the problem worse.