Gripping threaded parts

Gripping threaded parts

Cutting external threads is one of the more difficult machining operations. Achieving the proper thread form can be challenging, and tool chipping and premature tool wear are often problematic because of insufficient surface speeds and high cutting pressures.

Cutting external threads is one of the more difficult machining operations. Achieving the proper thread form can be challenging, and tool chipping and premature tool wear are often problematic because of insufficient surface speeds and high cutting pressures.

Nevertheless, there are many ways to successfully cut external threads, including chasing them with a die, single-point turning, whirling, rolling and milling. However, the worst aspect of machining a threaded part usually isn't making the thread, but gripping the part afterwards for doing a secondary operation.

Consider turning a knurled-head, socket head cap screw having dimensions of 1⁄2-13×2". A shop with a 2-axis CNC lathe would most likely load bar stock at least 9⁄16" in diameter into the feeder, face, chamfer and turn the major diameter and screw head, knurl it, cut the thread and part off. All that's left is to face, drill and broach the opposite end.

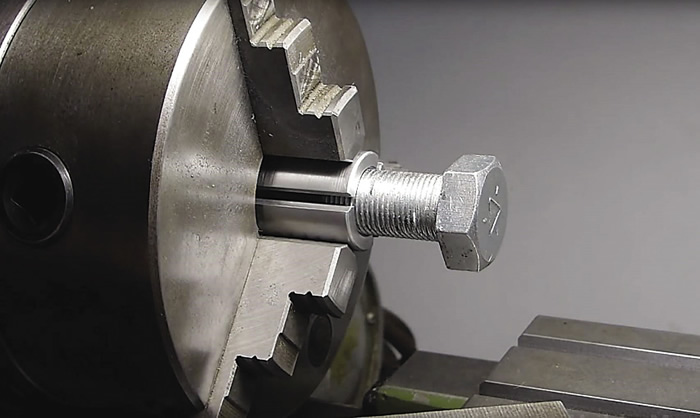

A split sleeve can be an effective method for gripping threaded parts.

But how do you grab the thing without damaging the threads?

For many machinists, their first inclination is to use the thread flanks and pitch diameter as the locating surface. One way to do this is by wrapping the thread with a length of copper wire, large enough in diameter so the collet or chuck touches the copper rather than the thread's major diameter. For low volumes and prototypes, this is a simple and cost-effective workholding method. The downside is the time-consuming wrapping and subsequent unwrapping of the bolt. Unless a machinist uses high-quality wire and carefully wraps the thread, concentricity between the first and second operations may suffer. This is not a big deal for a socket head cap screw, but many threaded parts require greater accuracy.

A similar approach is to thread a pair of nuts with a lock washer between them up to the head of the bolt and use a third nut near the opposite end to steady the assembly when placing it into a 3-jaw chuck or hex-shaped collet. This effectively grips the workpiece, but—as with the copper wire—success depends on the accuracy of the clamping nuts, and spinning the nuts on and off the workpiece is tedious at best.

Taken one step further, a threaded bushing can be made by drilling and tapping a 1⁄2-13 hole in tool steel—or another durable material—that's roughly twice the diameter of the thread, then slicing this ad hoc fixture into pie-shaped pieces. Clean the threads carefully to remove any burrs, place the pieces around the workpiece and locate the captured workpiece in the lathe chuck.

As with most parts, how the thread is gripped depends on what it will be used for. A 1018 steel fastener for a tractor engine, for example, has far less stringent requirements than one used to retain the landing gear on a fighter jet. Some companies might frown on engaging the threads of an aircraft or medical part in this manner, so it's important to check with the customer for form, fit and finish requirements. Always watch for scuff marks or other cosmetic damage when clamping on the thread flanks and pitch diameter, as previously described.

What material the bolt is made of also plays a huge factor in how it is clamped. Speaking from years of making threaded parts from difficult-to-machine materials, such as Inconel and stainless steel, many of which had tight form and diameter tolerances, one of the best approaches is to simply clamp on the OD with a hardened steel collet. This reduces the major diameter by a few tenths, but I never had any problems meeting print dimensions or holding concentricity in this manner. And, part slippage was not a concern, provided the clamping pressure applied was 30 psi or higher (the actual pressure applied depended on the workpiece size and configuration).

That said, this didn't work for me on aluminum or copper parts—the collet smashed the heck out of the thread crests. Nor did I have much luck with pie jaws or "emergency" collets. These are made of steel, aluminum or iron, which are soft enough to be machined to fit the workpiece and, at first glance, would seem a logical choice for this application. Their softness is their downfall, however, as the ID of the bored emergency collet or soft jaw was soon lined with grooves and creases from the part's thread peaks. Also, concentricity became an issue.