Horizontal machining centers’ enhanced capabilities shorten payback periods

Horizontal machining centers’ enhanced capabilities shorten payback periods

At roughly twice the price of a vertical machining center, do horizontal machining centers make sound financial sense? Absolutely, according to Scott Baldus, product specialist at Okuma America Corp. The Charlotte, N.C., machine builder offers both VMCs and HMCs, yet, Baldus noted, HMCs provide, on average, more than three times the spindle utilization of VMCs.

At roughly twice the price of a vertical machining center, do horizontal machining centers make sound financial sense?

Absolutely, according to Scott Baldus, product specialist at Okuma America Corp. The Charlotte, N.C., machine builder offers both VMCs and HMCs, yet, Baldus noted, HMCs provide, on average, more than three times the spindle utilization of VMCs.

"There are a number of reasons for this," Baldus explained. "Number one is that horizontals generally come standard with a pallet changer. While the parts on the first pallet are being machined, the other pallet can be loaded with more parts. When the cycle finishes, the pallet automatically changes. There's no time lost."

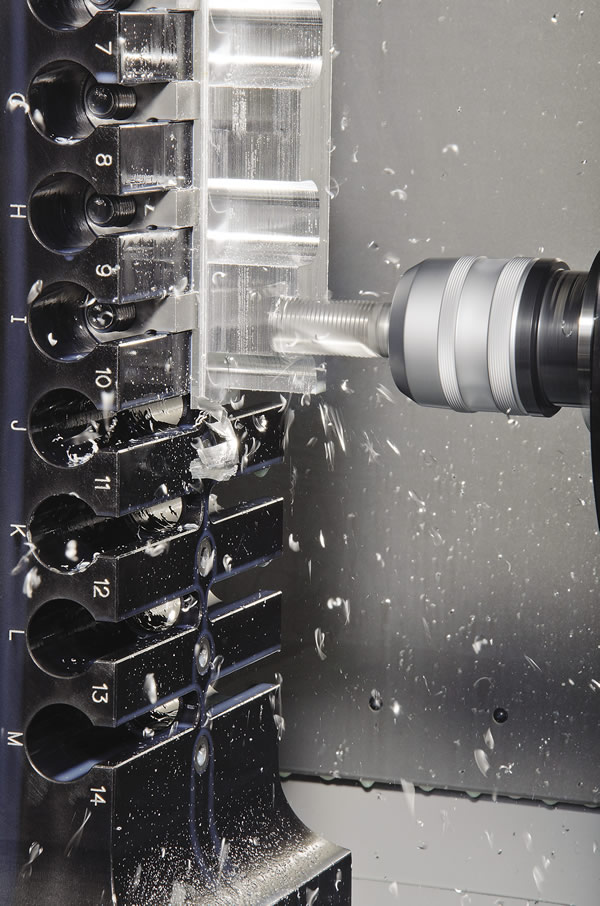

Greater part fixturing possibilities exist on HMCs compared to VMCs. Image courtesy Makino.

HMCs also accommodate more flexible workholding options, Baldus noted. Four-, six- and even eight-sided tombstones, double-sided window frames and dedicated hydraulic or high-density fixtures are common on HMCs, making them a favorite of high-volume shops. Prototype and low-volume manufacturers benefit as well from the ability to setup multiple jobs on each tombstone on an HMC.

But can't verticals be equipped with pallet changers and trunnion-style indexing tables, making them just as productive and flexible as HMCs?

Maybe, Baldus said, but the cost of those accessories can easily drive the price of a retrofitted VMC into HMC territory. (On average, an HMC costs about $200,000.) Z-axis travel is consumed by the height of a rotary trunnion table and shop floor space is lost with bulky aftermarket pallet changers. These can be lifesavers when choices are limited, but few would argue that bolt-on accessories are as effective as "from the ground up" HMC solutions.

"Horizontals also hold more cutting tools," Baldus said. "Our VMCs are usually limited to 36 stations, whereas horizontals can be equipped with 400-tool magazines, so you won't run out of tools when adding a pallet pool or linear pallet system. Also, HMCs offer advanced features, such as turn-milling, which combines spindle rotation with interpolation in the X-Y plane to generate 'turned' surfaces on milled workpieces. Verticals don't have that capability."

A Better Mousetrap

Okuma claims that, compared to VMCs, HMCs deliver 24 hours of additional productivity for every 40-hour workweek—assuming an HMC spindle utilization rate of 85 percent (compared to 25 percent for a VMC) and an hourly shop rate of $125. That adds $156,000 to the annual bottom line, easily enough to cover the cost delta between the two machine

platforms.

There's no argument about HMCs' benefits from Bernie Otto, KIWA product manager at Methods Machine Tools Inc., Sudbury, Mass. He said greater tool capacity, simpler and more-effective workholding and integrated automation are good reasons to buy a horizontal. Here's another: improved chip flow. Because the spindle is horizontal, chips can't accumulate in the work area. Instead they fall down and away from the workpiece, eliminating problems like chip recutting.

"The first question we ask potential customers is what kind of work they're doing," Otto said. "If they're machining a lot of pockets, for example, recutting can cause significant problems on a VMC. In these applications, tool life and part quality is improved due to a horizontal's better chip flow."

Otto conceded that some shops are scared off by the higher initial cost of a horizontal, as well as the cost to tool it, but he doesn't think they should be.

"Compared to 10 or 15 years ago, there's a lot of off-the-shelf workholding for HMCs. For a 12" pallet machine, you're probably looking at $6,000 or less for a set of four dual-position vises mounted to a tombstone," he said. "Yes, you'll need two of them—one for each pallet—so you're looking at $12,000 total for the workholding, but that's actually not a bad price considering the three to four times greater productivity available from a horizontal."

Investing $12,000 in workholding is enough to give many shop owners heartburn, especially when they're used to tooling a VMC with a pair of 6" machinist's vises for less than $1,000. Spending $20,000 or more on the additional toolholders needed for an HMC only exacerbates the heartburn.

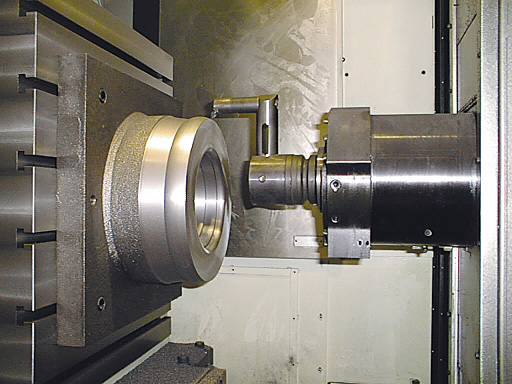

It might take getting used to, but machine operators can easily adjust to a horizontal world. Image courtesy Baum Precision Machining.

Still, it's hard to argue with the efficiency gains most shops see after taking the horizontal leap of faith. One such shop is Baum Precision Machining Inc. Before acquiring its first KIWA in 2008, a KNH-426X 2-pallet horizontal, the shop made all its parts on 3-axis VMCs, often requiring three to five operations. By allowing parts to be made in one or two operations, HMCs have greatly decreased the Pipersville, Pa., shop's setup time, said Aaron Baum, company president. And because multiple pallets mean multiple jobs are set up simultaneously, there's greater flexibility to meet changing customer demands.

Spindle utilization has increased to 90 percent or more during the 24-hour, 6-day workweek at Baum Precision. Because of this success, the company has since added a pair of 6-pallet-pool KIWA KH-45G HMCs and upgraded its original machine to match that pallet configuration. "We find one horizontal can do the work of three or four verticals," Baum said.

More Hurdles to Jump

Baum Precision's experience is typical of shops that have switched to HMCs, according to Otto. "They don't want to go back. They're no longer flipping parts across multiple fixtures, and they can machine more features per operation. Part accuracy improves, tooling costs go down and work in process is

reduced."

In the context of a return-on-investment evaluation, these concepts are often difficult to quantify, but are clear considerations when determining machine productivity.

Another consideration is machine tool friendliness. It's tough to beat the relative simplicity of most 3-axis machining. Programmers and machine operators are familiar with the up and down, side-to-side movements associated with VMCs. Coordinate systems are easy to visualize, and, in many cases, only a few work offsets are needed.

With HMCs, there are far more parts running per cycle. This might mean dozens of workpiece positions and pallets to track and require hundreds of cutting tools. Potential tool/fixture interference must be given greater consideration,

as must program storage, in-process probing and tool life management. With HMCs, there's simply more, more, more.

Fortunately, these hurdles are generally simple to overcome. CAM systems make easy work of such complexity, and HMC builders have equipped their wares with software to manage any number of tools, pallets and machines.

"The transition from vertical to horizontal is not as difficult as many think," Otto said. "You're still drilling holes; you're still cutting around parts. The majority of people are a little nervous at first, but after a couple months, it is business as usual—only better."

Being able to turn a workpiece on an HMC significantly expands its machining potential. Image courtesy Okuma America.

Taking the High Road

Mark Rentschler, director of marketing for Makino Inc., Mason, Ohio, said machine construction is one of the primary drivers of an HMC's superior efficiency. "You have to look at the greater rapid-traverse rates, the way tool changes are effected, and axial thrust and spindle torque characteristics. Horizontals are simply designed for higher rates of production throughput."

That's not to say HMCs are the end-all machining solution. A yard-wide piece of plate steel fits easily on most VMCs, but outstrips the capacity of all but the largest horizontals. Miniature electronic components might be better suited for production on a drill/tap machine. And for complex medical parts, a 5-axis VMC is tough to beat. As Rentschler pointed out, however, the built-in automation and workholding capabilities of horizontals make them kings of high-volume production.

Nonetheless, Rentschler warned that parts manufacturers should choose high-quality equipment from a reputable builder, suited for the type of work they do. Makino, he noted, produces machines for specific applications, including aerospace structural components made of aluminum and titanium. Those machines have operational designs and functionality completely different than a 4-axis horizontal running automotive parts or die/mold

components.

"For North American manufacturers to compete in a global market, it's paramount they embrace and invest in technology," he added. "In most cases, the greatest ROI is achieved with HMCs. Easier part handling, greater diversity of automated machine tending, more comprehensive systems to manage part flow.

"Manufacturers large and small need to consider these things and look at automation as a way to secure future competitiveness and grow their businesses. The world has changed dramatically in the last few years and will continue to do so. All of us have to look at manufacturing in a different light," Rentschler said.

Easy Terms

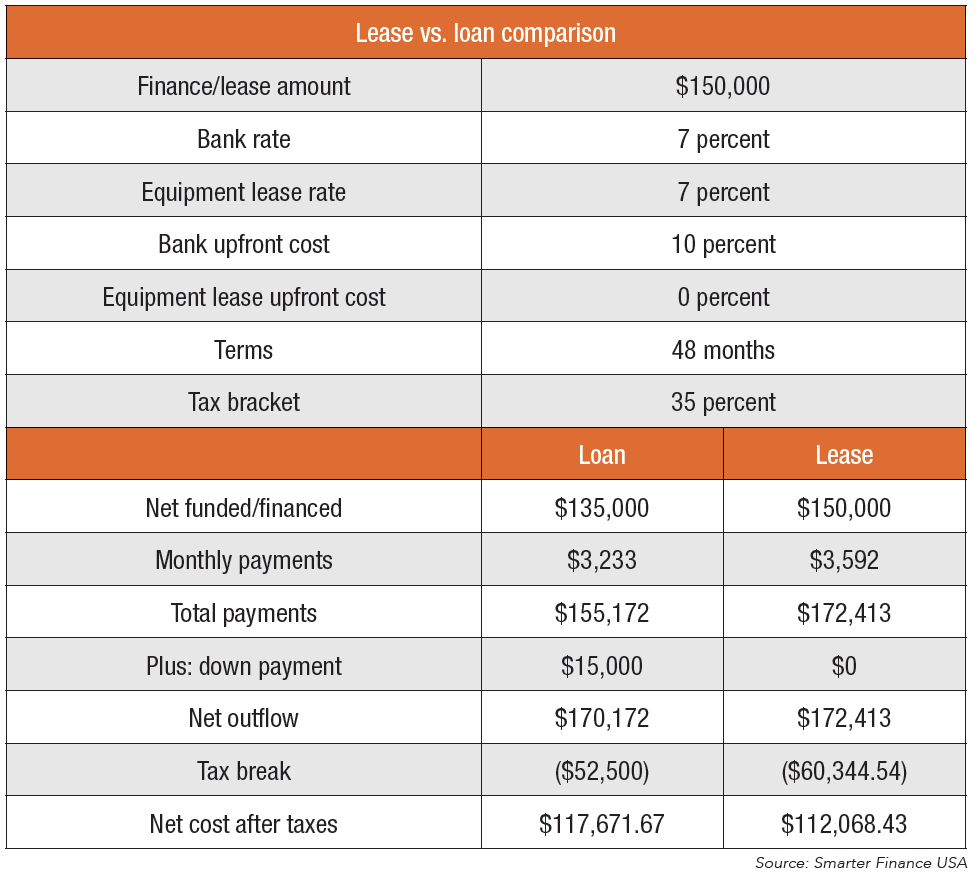

What's the best way to pay for that new horizontal or vertical machining center?

"It depends," said Rob Misheloff, president of Smarter Finance USA, Irvine, Calif. "Large shops look at very different and possibly far more expensive machines than do small ones and often have far different cash flows, credit ratings and tax considerations."

For businesses with large cash reserves, the simplest answer might be to make a sizable down payment or even buy the machine outright. This minimizes interest payments and gets the equipment paid off quickly or immediately. Misheloff warned, though, that paying cash may be unwise.

"Folks are usually poorly served by paying cash for a machine," he said. "It eats up working capital, and the tax advantages of leasing are often so great that financing costs after a tax rebate are free—or even less than free."

Less than free? Though not always the case, but Misheloff said companies with good credit can see significant savings by leasing equipment, once federal and state tax rebates are considered. Fair-market-value (FMV) leases allow shops to skip the down payment, pay less over the course of the lease and write off the monthly payment to boot. So-called "dollar out" leases are usually loans by another name, but do offer some tax advantages. And straight financing allows equipment to be depreciated over the loan term—or longer—but may cost more in the long run.

"Again, it really depends on the situation," he said. "Because a shop can turn in the equipment at the end of an FMV lease, it's easier to stay current on technology. Other shops think it makes sense to pay off a machine and run it for 20 years. We typically tell clients, the better your credit, the longer your term should be. On the other hand, start-up shops might want to pay off the machine more quickly, since lower credit scores mean higher interest rates. The best advice is to shop around, evaluate all the numbers and make sure you look at the big picture."

—K. Hanson

Contributors

Baum Precision Machining Inc.

(215) 766-3066

www.baumprecision.com

Makino Inc.

(800) 552-3288

www.makino.com

Methods Machine Tools Inc.

(877) 668-4262

www.methodsmachine.com

Okuma America Corp.

(704) 588-7000

www.okuma.com

Smarter Finance USA

(800) 919-8022

www.smarterfinanceusa.com