New Coatings Meet New Challenges

New Coatings Meet New Challenges

As the use of hard-to-machine work materials grows, the need for high-performance tool coatings increases. This article discusses developments in coatings that have increased their usability. Among the coatings discussed are medium-temperature CVD coatings and multilayer PVD coatings.

The bad news is, work materials are getting tougher to machine.

The good news is, tool coatings are getting better.

Some of the most promising cutting tool research being conducted today involves tool coatings. But don't look for the dramatic improvements achieved in the late 1960s and early 1970s when titanium-carbide (TiC), titanium-nitride (TiN), and aluminum-oxide (Al2O3) coatings were introduced to the cutting tool market. Today's developments figure to offer more subtle improvements in speed and tool life. While subtle, these changes will be crucial for machine shops dealing with increasingly difficult-to-machine work materials.

Since 1973, when Al2O3 coatings were introduced, improvements have consisted of new and better combinations of coatings and better ways of depositing them on tool substrates. Multilayer coatings with layer thicknesses tailored for intended applications have been around for 15 years. Control of layer thickness and uniformity continues to improve, and the coatings available now are more consistent and, therefore, more reliable than those available as recently as four years ago. Almost all multilayer coatings feature a base layer of either coated tools." title="Often used as a tool coating. See coated tools." aria-label="Glossary: titanium carbonitride (TiCN)">titanium carbonitride (TiCN) or titanium oxycarbonitride (TiOCN) for wear resistance and interfacial microstructural control. These special layers eliminate the brittle eta phase that used to result from carbon depletion at the coating/substrate interface.

End users' demands in recent years have concentrated on tool reliability and versatility. Toward this end, one of the most dominant trends over the next five years will be the continuing development and increased use of multilayer physical-vapor-deposition (PVD) coatings for superalloys and medium-temperature chemical-vapor-deposition (MTCVD) coatings for ferrous materials.

MTCVD coatings, as the name implies, are deposited at lower temperatures than CVD coatings. The lower temperatures eliminate cracks in the coating. As a result, MTCVD coatings offer the advantage of having increased toughness and smoothness without sacrificing wear resistance or crater resistance. Tools with these coatings cover broader application ranges for ferrous materials, allowing consumers to inventory fewer grades and, therefore, suffer fewer application mistakes.

The Material Revolution

| A TP100 Coating | A TP200/300 Coating |

|  |

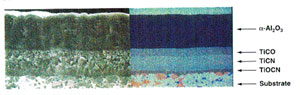

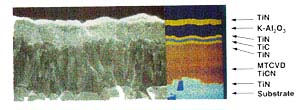

Figure 1: Scanning electron microscopy photographs of the microstructures of a multilayer CVD coating (A) and a multilayer MTCVD coating (B).

The need for improved, more versatile coated tools has arisen from shops encountering a wider variety of hard-to-machine workpiece materials than ever before. Trends in cutting tool materials either anticipate or reflect trends in the materials they are designed to cut. Increasing demands for stronger, lighter, more temperature-resistant, and more corrosion-resistant work materials have dictated what materials are to be machined. Those factors in turn determine the areas in which tooling producers spend their R&D resources. For example:

The demand for more fuel-efficient cars and trucks has led to an increased consumption of plastics and aluminum alloys and an anticipated increase in the use of magnesium and titanium-aluminide alloys. There is also an intensified desire for stronger steels and ductile irons, because these materials allow the production of strong, lightweight components.

The need for more fuel-efficient and quieter aircraft engines has led to the development of superalloys that are more pure, have higher temperature strengths, and are tougher.

The desire to reduce energy consumption and waste of material has led to an increased use of near-net-shape parts.

The need for longer-lasting materials in corrosive environments has led to an increased use of stainless steels and superalloys in the chemical, food, paper, and wood-pulp industries.

The need for faster fabrication has led to the increased use of exotic welds, many of which need to be machined.

Unfortunately for those involved in the metal-removal industry, almost all of these trends result in decreased workpiece machinability. Today's tools must cut materials that are stronger, tougher, and more abrasive. Tool producers have adopted various strategies for dealing with these work materials. The results have been mixed.

During the 1980s, some manufacturers attempted to combine thick, wear-resistant coatings with hard, deformation-resistant substrates featuring tough cobalt-enriched zones at the substrate/coating interface to make the ultimate "one-grade-does-it-all" tool. While substantial strides were made, the manufacturers could not create a panacea. Two major areas impeded this effort. First, whenever a tool gains in one area, it loses something in another area. For example, when a tool gains toughness, it loses deformation resistance and at least some wear resistance. Second, over time the cutting speed requirement for a general-purpose grade gets higher. In the mid-1980s, the target speed for a general-purpose grade was around 700 sfm for steels. By the early 1990s, that speed had increased to perhaps 850 sfm as manufacturers began to use faster, sturdier machine tools and machinists became more accustomed to using more productive tooling. However, the gap between general-purpose speeds and high-performance speeds did not narrow, because all tool speeds shifted upward.

Medium-Temperature Solution

MTCVD coatings offer a promising solution. While not ideal for all work materials, MTCVD coatings have an application range for advanced ferrous materials that is broader than other coatings' ranges. These coatings allow for the creation of simpler selection guidelines. The large number of tooling producers and the dizzying array of products that they offer can make tooling selection a complex process. With a limited offering of general-purpose grades and chipgrooves, it is much easier for the tool manufacturers to present logical selection criteria. For the tool user, the chance of making the right choice for a particular application increases dramatically.

Figure 2: A comparison of the toughness of CVD and MTCVD

Figure 1 illustrates the microstructural differences between CVD and MTCVD coatings. While the thicknesses of the different layers vary, it is apparent that the structure of the TiCN layer is different, depending on the deposition conditions.

Lower deposition temperatures yield crack-free coatings. Because the coating layers have differing levels of thermal expansion, cracks always form in traditional CVD coatings when the tools cool off after deposition. These cracks are clearly visible during metallographic analysis. Careful analysis has shown that few or no cracks are present in MTCVD coatings. This lack of cracking accounts in part for the increased toughness of these coatings. Semicoherent grain boundaries probably also contribute to toughness.

Figure 2 depicts the advantages of MTCVD coatings. Using a slotted log and the conditions shown in the figure, resistance to chipping and fracture was determined as a function of feed rate. Substrates, insert geometries, and edge preparations were identical on the two lots of material tested. A 1" length of material was cut before a trial was stopped. Ten edges of each type of coating were tested at each feed rate. As shown, above 0.006 ipr, the MTCVD coating was clearly tougher than the CVD coating.

This toughness is particularly advantageous for the machining of stainless steels. Stainless-steel use is growing and is expected to continue growing for years to come. Stainless steels typically are gummy and cause built-up edge (BUE) on cutting tools. When BUE is eventually pushed away, it can pull a piece of the coating and/or the substrate with it, a phenomenon called pick-out. The tougher MTCVD coatings resist pick-out more effectively than CVD coatings do.

Ductile irons also are becoming more popular, because they combine low production costs and good mechanical properties. These alloys are cheaper to produce than steels and are stronger and tougher than cast irons. That's why the use of ductile irons is increasing dramatically in the automotive, agricultural, and machine tool industries.

Unfortunately, these ductile irons also are very abrasive and notorious for wearing out tools quickly. As might be expected, the machinability of these materials is directly related to structure. As pearlite content increases, the abrasiveness of the iron increases and the machinability decreases. MTCVD coatings are particularly effective in machining these materials.

Grades that are effective at speeds of less than 1000 sfm usually contain thick layers of TiC or TiCN, because these harder coatings provide better wear resistance. As cutting speeds increase however, chip/tool interface temperatures also increase. This does two things. TiC softens faster with increasing temperature than does Al2O3, and the higher temperatures put more pressure on the crater resistance of the coating system. Thus, more stable coatings, such as Al2O3, become more effective as cutting speeds increase. While the particular speed and temperature at which the transition takes place depend on the structure and properties of the iron being machined, coatings with thick TiC or TiCN and thin oxide layers are preferred until speeds exceed 1,000 sfm.

Since most ductile irons are machined between 500 and 1100 sfm, the type of MTCVD coating shown in Figure 1B, combined with the proper tungsten-carbide substrate, is particularly effective in the machining of ductile irons. A thick titanium layer for wear resistance, topped with a thinner Al2O3 layer for some crater resistance, results in a broad-based coating system for these irons.

Coated Cermets and Ceramics

Many ferrous parts, particularly those made from powder metals or expensive steels, are produced to near-net shape. Machining these parts calls for lighter depths of cut (DOCs) and higher speeds. Cermets and PVD-coated cermets are tailor-made for such conditions. While more common in Japan than in the United States or Europe, cermets offer several definite advantages over other tool substrates. They offer greater flank-wear resistance, better surface finish, and a purchase price typically 30% lower than that of coated carbides. Surface finishes obtained with cermet tools and coated-carbide tools are compared in Figure 3.

Currently, cermets are the subject of a great deal of research. This research has led to improved cermet materials. Several of the newer cermets are higher in binder content. That makes them tougher and softer. As a result, coatings, particularly PVD coatings, have become essential for cermet tools. That's because, to make cermets more broadly applicable, more binder is added to increase toughness. However, the increased binder content also makes them more susceptible to wear, making PVD coatings a necessity. PVD-coated cermets should become more popular with time.

Ceramics also figure to increase in popularity. While Al2O3-base ceramics are hard and thermally stable, the tougher ceramics - silicon nitride (Si34) and Al2O3 reinforced with silicon-carbide fibers - are sometimes limited by the chemical interaction with the work material. As a result, coatings can substantially increase the life of these tougher ceramics, particularly when machining ductile irons, which generate heat during chip formation. While some of the earliest work was done on Al2O3-coated, whisker-reinforced ceramics, most interest today focuses on TiN-coated Si34. This coating broadens the application range of the tougher ceramics.

High-Temp Alloys

For the machining of superalloys and titanium-base alloys, PVD-coated micrograin carbides, as well as ceramics and cubic boron nitride (CBN), offer the best results.

Micrograin carbides have had a major impact on tool life and tooling reliability, the latter often being more important than the former when it comes to machining expensive superalloy materials. The demand for higher turbine-engine operating temperatures has led to the advent of alloys that retain their strength at higher and higher temperatures. The average temperature at which a new alloy can be used has increased at a rate of about 16° F per year, and there is no indication that this trend will change. New methods are being employed to produce and process superalloys to improve their mechanical properties, which also makes them tougher. As with ferrous materials, superalloys are becoming more difficult to machine as their properties improve.

Figure 3: A comparison of the surface finish obtained when machining 1045 steel with an uncoated cermet insert and with a CVD-coated cemented-carbide insert.

As the high-temperature strength of superalloys increases, the force imposed on the cutting edge of an insert also increases. While C-2 carbide used to be acceptable for many titanium- and nickel-base alloys, C-2 edges are now crushed and suffer severe DOC-line notching when machining advanced versions of these materials. Micrograin carbides have much higher compression strength and hardness than regular carbides while sacrificing only a small amount of toughness. Consequently, they resist breakage and notching more effectively.

Micrograin-carbide substrates become even more effective for the machining of newer superalloys when teamed with PVD coatings. TiN, the first PVD coating, is still the most popular. Recently, titanium aluminum nitride (TiAlN) and TiCN coatings have been used with good results. TiAlN coatings are effective when cutting speeds can be increased. The range of materials TiAlN can machine is narrower than TiN's, but when operating in its niche, TiAlN can increase productivity as much as 40% over TiN. Attempts to use TiAlN at lower speeds can result in BUE and subsequent chipping and pick-out if the coating's surface condition is not ideal. TiCN is harder than TiN or TiAlN and offers greater tool life, especially in milling operations. Strides are being made to increase the smoothness of the TiAlN surface, which could minimize BUE.

Recently, several layers of these coatings have been combined. In-house and field testing has proven that such combinations can be effective over broader application ranges than any one of the coatings by itself.

Like multilayer MTCVD coatings, multilayer PVD coatings are expected to see greater use and for many of the same reasons. Along with coated cermets and ceramics, these coating technologies should continue to improve gradually for years to come. The chief foreseeable breakthrough likely to occur in the next decade is the development of usable CBN coatings. Until then, current coating technology will continue to create better and better

About the Author

Donald Graham is manager of turning programs for Carboloy Inc., Detroit.