Tips, techniques for nonperpendicular holemaking

Tips, techniques for nonperpendicular holemaking

We called them "submarines." Tough, 17-4 PH stainless steel forgings shaped like miniature German U-boats, each requiring several ¼" (6.4mm) through-holes to be drilled at a 25° angle. Each sub was loaded into a jig that held it at the required angle, and a metal plate fitted with hardened steel bushings was then clamped to the top of the jig before the holes were produced with a drill press.

We called them "submarines." Tough, 17-4 PH stainless steel forgings shaped like miniature German U-boats, each requiring several ¼" (6.4mm) through-holes to be drilled at a 25° angle. Each sub was loaded into a jig that held it at the required angle, and a metal plate fitted with hardened steel bushings was then clamped to the top of the jig before the holes were produced with a drill press.

Chips and cutting fluid flew everywhere. And because the drill would occasionally shatter on breakthrough, shrapnel was always a concern. It was mindless, tiring work, and there was an unspoken rule that all new employees had to spend their first week drilling submarines, upon which they could graduate to one of the NC mills or chuckers.

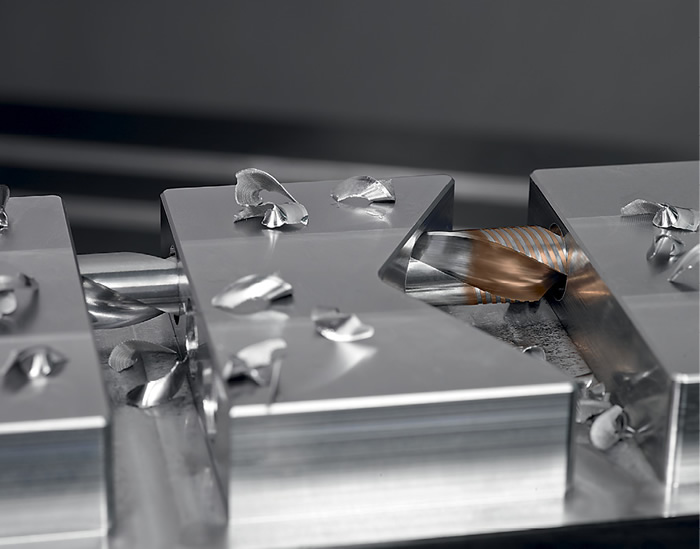

Image courtesy Walter USA.

A Light Touch

Even today, a drill press with a bushed fixture is a cost-effective way to make large numbers of holes, especially when they are not perpendicular to the workpiece surface. That's because the bushing supports the drill, preventing deflection as it enters the workpiece, and the ability to feel the drill when it breaks through allows an operator to

manually reduce drilling pressure, hopefully avoiding breakage.

That's certainly the hope of Dave Fagan, shop foreman at Washington Machine Works, a Seattle job shop that specializes in low-volume, complex parts for the nuclear, marine and other industries. Fagan said the quantities at WMW are small enough that bushed drill jigs are rarely necessary. Instead, machinists rely on their sense of touch to guide drills during angled holemaking.

"A lot of our work is done on a Bridgeport," he said. "It gives you a certain sense of touch, something you don't feel on a big horizontal boring mill or other large manual machine, where much more iron is moved when you turn the handles."

The flute design of the Walter DC170 drill creates support around the periphery of the tool to prevent chatter and drill walking when making angled holes, according to the company. Image courtesy Walter USA.

One job that needed a delicate touch was a 316 stainless axle shaft for a cable drum. Fagan said WMW straddle-clamped the shaft directly to the Bridgeport table, tipped the head 45°, found the centerline and then spotfaced a small flat with an endmill at the required location. Next, a HSS jobber drill was applied to punch through to a cross-hole, into which a length of cable would later be fed.

"There are different ways to go about it," Fagan said. "You could just as easily tip the part to the required angle with some sine blocks. What's important is that you do the math and get the hole in the right spot. And you need a good feel for the drill as it breaks through, because it can catch and break. That's why we like to use HSS, since it's a lot more forgiving than carbide."

The angled hole on this shaft required a delicate touch while being drilled on a knee mill. Image courtesy Washington Machine Works.

Maximizing Margins

Luke Pollock, product manager at Walter USA LLC, Waukesha, Wis., said that regardless of the machine tool, one of the best solutions for angled holemaking is a four-margin drill. "A drill with two margins per cutting edge provides more contact between the tool and the workpiece material," he said. "It helps guide the tool and prevents drill walk, especially as you break through the back of the part."

For relatively shallow holes where the centerline is close to perpendicular, it's often possible to drill without a starter hole.

"I wouldn't do that on very tough materials or where high positional accuracy is required, but on depth-to-diameter ratios up to maybe 8:1, you can often just start drilling," he said. "Another option is our DC170 drill, which, because of its flute design, offers support around the entire periphery of the drill point. It basically acts like a bearing surface, preventing any chatter or drill walk on exit."

For most angled drilling, Pollock recommends reducing speeds and feeds by 30 to 50 percent when starting and exiting a hole. If a starter hole is required, he said many shops don't drill one. Instead, they use a center-cutting endmill to create a flat the same size, or slightly larger, than the drill's diameter. He added that a better option than endmilling a flat is to apply a dedicated pilot drill with a 180° point, because it has greater metal-removal capabilities and improves accuracy and tool life.

Magnetic Personality

An annular cutter is another alternative to a jobber drill when making an angled hole. Also known as a Rotabroach, an annular cutter looks like a hollow endmill. It works by removing a ring of material the same size as the finished hole. The center portion inside of the ring remains intact and is ejected once the cutter is removed from the hole.

Because annular cutters remove only the outer periphery of the hole, horsepower and thrust requirements are far lower than traditional holemaking tools, making annular cutters a favorite for magnetic and hand-held drilling. Yet Allan Powers, technical applications lead at Hougen Manufacturing Inc., Swartz Creek, Mich., said Rotabroaches are a popular holemaking alternative on CNC machines as well, especially when spindle power is limited.

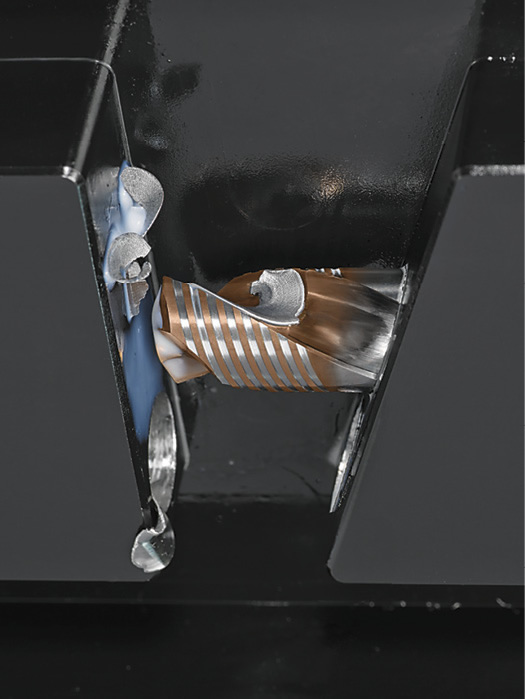

Some angled holes call for complex, compound angles that have matching geometry with other machined features. A drill bushing ground with these special angles is not practical or economical in these cases. Image courtesy Unisig.

"Annular cutters are also effective on angled holes, provided the centerline is no more than 20° from perpendicular," he said. "Unless it's soft material, like aluminum, the lateral loads become too great, and you run the risk of breaking the cutter. We recommend reducing feed rates until the cutter is fully engaged, but, because the tool is largely self-supporting, there's no need to slow down on breakout."

Powers also recommends using a bushing to support the drill. Contrary to conventional wisdom, however, he suggested it be made of brass or other soft metal and not hardened steel.

"One of our customers had an angled hole application and found that the chips would curl back in and get caught between the steel bushing and the cutter, causing it to bind," he said. "By switching to brass, they improved chip evacuation and completely eliminated the problem. We've since validated their approach with our own in-house testing."

Hole Accuracy and Burrs

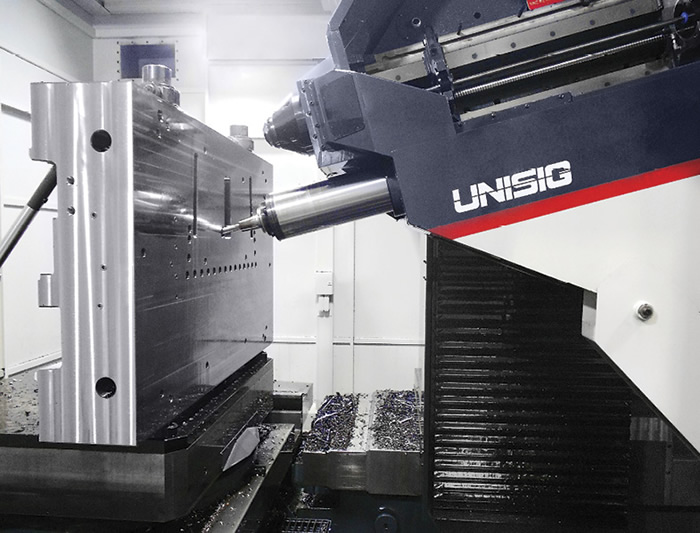

Someone who's a firm believer in drill bushings—although probably not ones made of brass—is Anthony Fettig, CEO at deep-hole drilling system provider Unisig, Menomonee Falls, Wis. He said the company has "drilled some really strange holes with pretty significant complexity and close tolerances." His first questions when quoting a job are often: What accuracy is required, and what burr condition is allowed?

Gundrilling relies on a bushing to guide a single-flute, noncenter-cutting drill into the workpiece. This bushing also acts to contain a stream of high-pressure cutting oil. Drilling an angled hole in an automobile crankshaft bearing journal, for example, requires a specially designed bushing with a concave face that conforms to the journal surface. Together with some clever grinding of the drill point, use of wear pads along the drill periphery and the proper application of speeds and feeds, holes can be predictably and accurately gundrilled by the hundreds of thousands.

Annular cutters, originally designed for use with manual and magnetic drills, are increasingly used on CNC machine tools. Image courtesy Hougen Manufacturing.

One of the biggest challenges with any angled-holemaking operation, Fettig said, is burr control. Because cutting fluid pressure around the drill tip falls to near zero when a drill breaks through into a cross-hole or out the back of the workpiece, chip evacuation is compromised while heat in the cutting area increases.

Second, even specialty drills like the ones used in high-volume gundrilling are unable to cut effectively with only one side of the tool engaged, as this creates nonuniform drilling forces. The result is that workpiece material tends to extrude rather than shear, and a larger than normal burr is formed.

Holemaking up to 20° from perpendicular is the rule of thumb for most annular-cutting operations. Image courtesy Hougen Manufacturing.

Another common problem, Fettig said, is inspecting intersecting holes, such as those seen in injection molds and a large number of automotive components.

"When you're drilling a pair of holes 0.080" in diameter that intersect 4" to 6" inside the part, there's no real way to inspect them accurately," Fettig said. "A CMM does a good job of projecting where the holes should meet, but there may have been some drill walk or deflection along the way. About the best you can do is use a borescope to inspect the hole intersection."