Turning the hard way

Turning the hard way

What is takes to turn the hardest metals.

When turning metal, the tool material must be four times harder than the workpiece. This becomes a problem when cutting metals with a hardness greater than 45 HRC, such as alloy steel, high-speed steel and chilled cast iron.

The hardest material is diamond, and polycrystalline diamond cutting tools work well for turning nonferrous materials like ceramics and aluminum. But the iron in steel reacts to diamond at the high temperatures generated by hard turning, causing excessive tool wear.

"Certain aluminum oxide ceramic-grade inserts can be used for hard turning, but not all ceramics can hard-turn," said Brian Sawicki, business development manager for the Northeast region at Tungaloy America Inc. in Arlington Heights, Illinois. "Sometimes you can get away with using ceramic inserts, but you can't use them in interrupted machining, such as face turning gear teeth, because they will fracture."

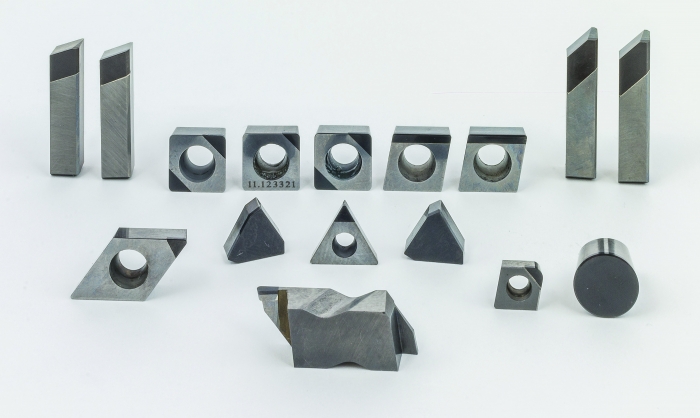

An alternative to ceramics and diamond, cubic boron nitride is the second-hardest material, and CBN tools of many grades have been developed for hard turning applications like transmission shafts, constant-velocity joints and toolholders. These inserts are used to finish-turn hard materials and produce fine finishes and tight tolerances, replacing grinding, which takes longer and costs more.

Chips entangling on workpieces or piling up at the bottom of machine tools can be prevented with the HP-style chipbreaker on the BXA10 range of coated CBN-grade inserts. Image courtesy of Tungaloy America

"Depending on the specifics of the job, you could source a $500,000 grinding machine, or you could buy a $100,000 lathe and do the same thing with hard turning," said Travis Coomer, national key account manager for GWS Tool Group in Tavares, Florida. "As long as you can attain all the tolerances given to the part, then it's absolutely a no-brainer to use hard-turn inserts as opposed to grinding."

Choosing Inserts

Hard turning is commonly considered to start with materials of 45 HRC, with a transition zone up to 50 HRC. In that zone, some harder carbide and cermet inserts still work. Coated and uncoated ceramic grades work for a hardness range of 45 HRC to about 60 HRC while CBN inserts are designed for about 50 HRC to 68 HRC.

Within the overlap of these ranges, choosing between ceramics and CBN depends on the application.

"Most ceramic grades don't have a high breaking strength," Sawicki said. "Whisker-reinforced ceramics generally have the highest breaking strength. But through an interrupted cut, it's way more predictable to run CBN than ceramic because once a ceramic insert starts to show flank wear, many times it just chips out due to excessive tool pressure."

But he advised against making the mistake of using a CBN insert on material with a hardness of less than 50 HRC.

"When you put CBN in a soft material," Sawicki said, "it begins to feel drag, which quickly erodes the insert, so your in-cut time is much lower in softer materials."

In contrast with ceramics, CBN signals it's starting to wear.

"You may start to see a change in surface finish that tells you this edge has reached its (end of) life," said David Essex, turning product manager at Tungaloy America. "Typically, operators will have worked out a part count and know, for example, this grade on this part will give you 50 pieces easily. So they change the insert at that point because it is

predictable."

Many CBN grades are available and often are designed for continuous-cut steel, heavily interrupted steel or moderately interrupted steel. Once a grade is selected, Coomer said choosing the right edge preparation and hone for the insert can minimize tool wear, lighten tool pressure, improve crater wear resistance and help a tool last longer.

"To protect the cutting edge," he said, "we can vary the angle coming off the top of the insert anywhere from 10 degrees to about 35 degrees down from the horizontal to direct the cutting forces into the tool and away from the edge."

GWS Tool Group's custom high-performance ISO inserts with various tip options, including single tip, double tip, full top and special, can accommodate any hard turning application. Image courtesy ofGWS Tool Group

It's important to match the combination of the CBN grade and the edge preparation to the application, said Brian Wilshire, technical center manager for Kyocera Precision Tools Inc. in Hendersonville, North Carolina.

"There's a fine balance you walk to pick a large enough edge preparation so that you get standard wear and no chipping," he said. "But if you pick too large an edge preparation, it's not going to last as long. You can consider it almost pre-worn because you're grinding a portion of the cutting edge away to strengthen it."

The Question of Coolant

Whether to use coolant is a substantial concern when hard turning and depends on the tool and application.

"Our ceramics definitely get better tool life running dry," Wilshire said. "So in most cases, when we recommend ceramics for hard turning, we prefer no coolant."

For CBN, he said, coolant can be used in a continuous cut with little difference in tool life.

Cooling does produce a part that's more in tolerance.

"If there's gauging immediately after machining, it's easier to get a true measurement if the part stays cooler," Wilshire said. "But if you run without cooling, the part heats up and tends to expand. So the part may be in tolerance when it's gauged, but as it cools off, it may shrink enough to go out of tolerance."

Interrupted cuts don't fare well with coolant, however, due to rapid thermal expansion and retraction as the tool moves in and out of the workpiece material.

"Using coolant for an interrupted (cut) will create thermal shock in the CBN," Wilshire said, "which will cause small fractures and quickly destroy your edge. We always tell customers, if they are running coolant, to make sure the stream is not interrupted, which could happen if the pump cavitates or if the geometry of the part shields the coolant line from the insert itself."

Where running coolant won't work, he said, an air blast could be used to keep a part cool, though that's less effective.

Chip Control

In general, chip control is less of an issue with hard turning due to high temperatures that cause ribbons of bright red, molten steel to flow off workpieces. Coomer said chips from hard materials are so brittle that they tend to crumble in one's hand, so CBN inserts for hard turning don't often come with chipbreakers.

However, even during hard turning, there are cases when chips may wad up and create issues with fixturing, workholding or surface finish — and harm tool life as well.

The KBN05M indexable insert works for high-speed finishing, as well as interrupted machining of hardened steel. Image courtesy Kyocera Precision Tools

"For example," Coomer said, "when you're hard turning internal bores, even though the chips may be free flowing, you might get into some bird nesting issues where chipbreakers might help."

Wilshire said another application for a chipbreaker would be when turning casehardened materials.

"The outer surface is hard," he said. "But as you get deeper into the part, it gets softer, and a chipbreaker can help curl the chip to keep it from scratching the softer surface underneath."

"Nowadays," Sawicki said, "a lot of high-production cells use robots to take parts out of one chuck and put them into another chuck or onto an inspection table, so you cannot afford to have chips hanging up on the workpiece. The ultimate chip control is using a chipbreaker plus high-pressure coolant at the tip with a coolant-through toolholder, so you're pretty much guaranteed the chip is going to go into the bed of the machine."

More Considerations

For parts with ultratight tolerances, Sawicki said CBN holds size much longer than ceramics. The lubricating and cooling effect of coolant helps with tolerances while providing a better finish, he said, and wiper flats on the inserts may improve the finish and reduce cycle times as well.

"Because the material is much harder, the cutting forces in hard turning are much higher, and any play in the ballscrew or in the ways of the machine is going to be magnified," Wilshire said. "So select the most rigid machine available and go up to the largest shank on the toolholder, with the shortest overhang, the strongest insert shape and the biggest corner radius possible for the part."

Coatings are available for ceramic and CBN inserts to resist wear, prolong tool life and increase speed, which is all-important for production machining. Coated inserts are more expensive, but Wilshire said the increased cost for a CBN insert is not that much.

"I would say 90% of the time coated is going to be better," he said. "But I have seen in some cases where uncoated might give a slightly better surface finish than coated, especially with the ceramics."

Another tip is to pre-chamfer the edges of the part and any drilled holes before it is heat-treated.

"This lets the hard-turn insert ease into the cut from a lighter depth of cut to the full depth of cut without hitting that hard corner," Wilshire said. "That minimizes the shock as it goes from no load to cutting loads, which can help prolong tool life — and it's less machining they have to do in the hard turn."

Best Practices for Hard Turning

Brian Sawicki, business development manager for the Northeast region at Tungaloy America Inc. in Arlington Heights, Illinois, shared best practices for hard turning.

"If the size of the workpiece you're turning is 1.25" (31.75 mm) or greater, I prefer using an 80-degree rhombic insert with a 32nd nose radius, which is the most common type of CBN insert," he said. "As the diameter gets smaller, you want to transition into a screw-down positive insert with a front relief angle because it's more important to be on centerline on smaller components than it is larger components. You'll be able to hold size and finish better."

Sawicki said good starting parameters for hard turning alloy and tool steels include:

- 122 m/min. (400 sfm)

- 0.1016 mm (0.004 ipr) feed rate

- 0.1016 mm to 0.254 mm (0.01") per side depth of cut

"You're safe 99.5% of the time running those operating parameters in any hard turning application for most materials above 50 Rockwell C hardness," he said. "If you're closer to 50 Rockwell C, start with 500 sfm (152 m/min.). And if you're hard turning D2 tool steel, start at 300 sfm (91 m/min.) or 350 sfm (107 m/min.)."

The goal is not to maximize speed.

"If you double the speed from 400 to 800 sfm (244 m/min.), you'll get far fewer parts per corner and perhaps less than five minutes of in-cut time," Sawicki said. "You may get done much faster, but you'll need to offset your tool more frequently in order to compensate for the tool wear that higher speeds induce."

He recommends programming a CNC for a constant sfm rather than a constant rpm.

"I prefer coding G96 for constant sfm," Sawicki said. "Then, as the diameter changes and you get closer to the centerline of the spindle, it's programmed to speed up the rpm to keep that sfm constant and to give you more consistent and predictable wear on your insert. If it were programmed in G97, which is a fixed rpm, it's going to feel drag as the part gets smaller. And CBN is sensitive to drag." — Holly B. Martin