Whitepaper: Benefits of combining cutting operations in a single tool

Whitepaper: Benefits of combining cutting operations in a single tool

Combining operations in a single tool is a significant trend sweeping through the metalcutting industry. Combining cutting operations reduces the cost per hole by eliminating tool changes. It improves production efficiency and machine utilization, ultimately increasing manufacturers' speed to market.

Combining operations in a single tool is a significant trend sweeping through the metalcutting industry. Combining cutting operations reduces the cost per hole by eliminating tool changes. It improves production efficiency and machine utilization, ultimately increasing manufacturers' speed to market.

The only thing preventing many manufacturers from combining operations is the perception that step tools are far more expensive than standard tools. However, the cycle time savings alone makes it worthwhile. Plus, combined step tools can be factory reconditioned, making combining cutting operations an extremely cost-effective proposition.

Efficient machine utilization affects a company's ability to get its products to market quicker – and speed to market has a major effect on the bottom line. Machines are expensive and labor costs are even more so, so utilizing those expensive machines to the maximum is the name of the game. This can be done by combining operations in one cutting tool.

Most shops have one operator to run multiple machines. The more tools used to perform an operation, the more setup time is required. Using one tool instead of three or four reduces this set up time, contributing to the cycle time reduction. It also lessens the amount of perishable tooling inventory. In addition, combining operations on one tool controls hole dimensions, forms, and shapes. It gives users the ability to hold critical tolerances, improving dimensional control, and hence production consistency.

Typically, high-production contractual/production shops doing repetitive work would benefit most from combined operations. Smaller job shops that only do a few pieces or run prototyping jobs would not gain as much from combined tool operations. Typically, a company would use multiple standard tools to prototype a part to demonstrate their capability of making the part. During production, they would look to switching over to a tool that can do as many operations as possible.

Modern manufacturing shops primarily use CNC machines; combining operations means they can use one tool to drill, chamfer, back chamfer and even mill. This is much better than using a machine that can only perform one in and out movement.

For example, combining operations in a CNC machine may facilitate circular interpolation, in which a rotating tool can follow along a circular arc. This can be a huge advantage in drilling bores with O-ring grooves. The CNC tool can be used to go in and out and also perform the circular motion needed to form what is required. So, by using CNC technology operators could drill to open the hole, then circular interpolate with an endmill feature and then finally chamfer to break the sharp edges – all with one tool.

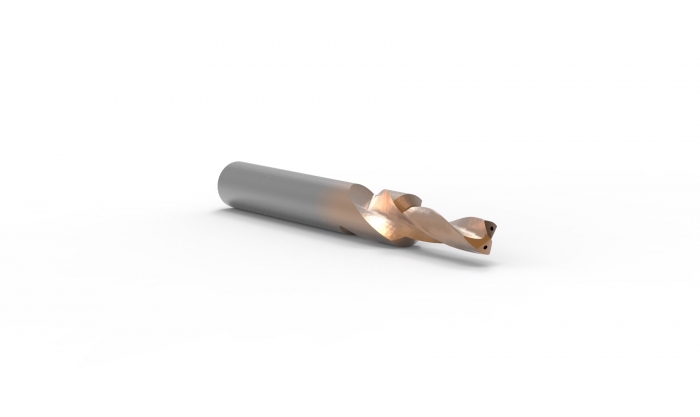

A Superion solid-carbide step drill. Images provided by Superion, an Allied Machine & Engineering company.

Another advantage of step tools is for forming complex forms, such as cavity ports that have multiple angles running into radii. The end user can control all tolerances in the tool and would not have to program the complex information into several tools to complete that same difficult form. This means it will result in higher accuracy and faster production, while also maintaining consistency, especially in complex forms.

One key example is SAE and/or ISO hydraulic ports, which feature forms with multiple angles and radii that all need to be controlled within each other. This combination of critical features makes them difficult to produce without a step tool. With combined tools, the port can be drilled from solid to a finished port all in one shot. This can be a significant time saver. All CNC machines use toolchangers, and moving from one tool to the next may take as much as 10 to 30 seconds of cycle time. Remember, in production shops, every second counts.

Many new tools are being developed to support recent advancements in raw materials, especially for aerospace and automobile applications. For example, aircraft are being manufactured with lightweight, extremely strong materials, such as carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) and carbon fiber-reinforced thermoplastic (CFRTP), which are extremely abrasive and difficult to machine. Machining with carbide tools is possible, but the tools wear out very quickly. This has led to the development of tools made with polycrystalline diamond (PCD).

PCD step tools can combine roughing and finishing operations, so operators can drill, mill and ream with one tool.

Many are looking for PCD step tools that can combine rough operations with finishing operations, so operators can drill, mill, and ream with one tool. The combined PCD tools are also being used in the automotive industry for abrasive high-silicon aluminums.