‘Poly–poly–or what?’ third part – hard turning

‘Poly–poly–or what?’ third part – hard turning

We are in part three of our article series "Poly–poly–or what?" The series looks back at the time between autumn 1974 and the Hanover Trade Show in the spring of 1975. Dealing with this new cutting material "polycrystalline diamonds" (PCD) was fascinating for all of us; after the presentation at the first Hanover Trade Show in 1973, each day brought new insights for production and for different applications.

We are in part three of our article series "Poly–poly–or what?" The series looks back at the time between autumn 1974 and the Hanover Trade Show in the spring of 1975. Dealing with this new cutting material "polycrystalline diamonds" (PCD) was fascinating for all of us; after the presentation at the first Hanover Trade Show in 1973, each day brought new insights for production and for different applications.

The diamond cutters—familiar with the production of natural turning diamonds and polished turning diamonds for the jewelry industry and for the turning of copper commutators—were especially amazed by the superior cutting abilities of this new material in comparison with natural diamonds.

For example, interrupted cuts are almost in all cases disastrous for natural diamonds. PCD allows for high feed rates up to the cutting width (even for the now available "large" PCD cutting edges), while natural cutting edges only allow for a range within microns or up to 1/100mm for selected materials.

Despite this fact, or now more than ever, development, production and application of the first PCD tools was successful in the end; it was a team effort and based on the professional know-how of diamond cutters such as Konrad Wagner, a master of natural diamond grinding who unfortunately died much too early, and Gerhard Mai with the assistance of machining expert Kurt Hemerka (grinding wheel production).

Polycrystalline diamond materials resisted even the most artistic skills of natural diamond cutters on traditional cast grinding wheels ("poly" means "much" and does not have any growth to guide the trained eye of a diamond cutter). A grinding test on a resin-bond grinding wheel, manufactured by Lach Diamant, proved to be so successful that we started to look for a stable and precise tool grinding machine. We found a machine manufactured by Kelch, which we co-developed especially for PCD grinding. After a license transfer, we continue to build the »pcd--‐100/300« precision tool grinding machine for single-tipped PCD and carbide tools.

All this obvious excitement, only one and a half years after the first PCD introduction in 1973, brings to mind another great innovation. "Start with Borazon," the abrasive of a new era, had been presented at Hanover Trade Show in 1969. Borazon CBN grinding wheels from Lach Diamant are so well known among tool grinders—as tool and inside grinding wheels, with increase production as peripheral wheels for surface and circular grinding—that the name "Borazon" is clearly associated with Lach Diamant. I had expected a PCBN cutting material back in the beginning of 1973—a sort of "compact Borazon cutting edge."

Moscow Beckons with a New Cutting Material

As luck would have it, we received an inquiry from Hempel, Düsseldorf, which had good business contacts to Moscow and the company asked whether we would be interested in a new cutting material named "Elbor" manufactured in the USSR, a compact CBN material compressed through high-pressure synthesis. Of course, yes! Electrified would be an understatement. And so it happened that Konrad Wagner and I flew to Moscow from East Berlin in 1974 in a Tupolew first-class as VIPs, organized by Hempel. The impressions and experiences of this short trip right before Christmas to an, at the time, unknown world for us, would be worth a separate report.

We found out that we got to Moscow at the invitation of the Russian Ministry of Food and Agriculture. This government department supervises 15 high-technology institutes and manufacturers for synthetic diamonds and CBN. At that time, we visited the Tomilinsky Factory near Moscow, founded in 1959, and according to the factory's accounts, one of the leading manufacturers of diamond tools in the former Soviet Union and, from the 19060s onwards, also a manufacturer of diamond and CBN grains. Here we should get to know Elbor.

The "new" cutting material, then unknown in the Western world, is for hard machining. By that time, we were very familiar with Borazon CBN grinding wheels, made from high-alloy hardened steel with a hardness of 58 to 62 HRC. Compared to grinding, it should be easy to use this CBN composite mixture (unlike diamonds stable up to 1,500° C) for the superior turning of these steels.

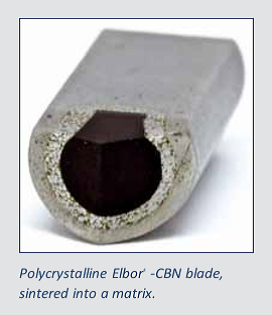

However, the CBN composite material named Elbor consisted of a unit with an 8mm radius and a thickness of about 6mm. There was no carrier—or carbide layer, which would have provided for a solid, sintered joint. We found comfort in the thought that we would, as usual, find a solution to achieve a stable connection between Elbor and a holder.

A license contract for the raw material Elbor was signed. Unfortunately, on Dec. 22, shortly before our return flight, we had to cancel a visit to the top secret "Institute for Super Hard Materials V Bakal" in Kiev, Ukraine. We had an invitation from the ministry, and the ministry would have even taken us by helicopter to this research facility, with up to 1,000 employees.

Unexpected Help by Coincidence

Back in Hanau, we started our first preparations for the Hanover Trade Show in 1975. What should we do with Elbor? We received unexpected help by coincidence, sure enough via Borazon. A "customer problem" in regards to surface grinding a metal powder coated cylinder. The customer thought that grinding times with the CBN wheel were too long. "Well, let's try this compact CBN Elbor. However, as expected, soldering with a carbide holder, as with PCD, was unsuccessful.

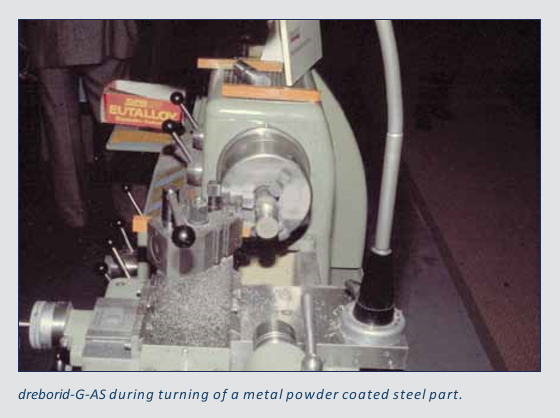

At that time, we did not have the option to solder within a vacuum, and so we had to sinter the Elbor cutting edge. The first attempt at making a turning tool in this way was already successful. This will be our trade show highlight—we will demonstrate it on a Weiler lathe. And so it happened: At the Hanover Trade Show in the spring, the "new" product was successfully presented as "dreborid-G-AS" for machining of metal powder-coated turning parts.

For the first time, hours of grinding times were reduced to minutes of turning times, and the surfaces were just as polished. The first step towards better performance and more efficiency was done. At first it was only a niche market, mainly Metco

(today Oerlikon‐Metco) and Castolin, among other manufacturers for metal powder coatings, considered the dreborid-G-AS turning tools almost as a gift. Too many customers complained about long grinding times during the equalization of flame-sprayed turning parts with nickel, chrome and carbide alloys—no matter whether for repairs or wear protection. Right away, we achieved up to 90 percent reductions, turning instead of grinding.

The Search for Other Possible Applications

During the initial phase, Metco and Castolin provided all their technicians, and Lach Diamant developed repair kits that contained one dreborid-G-AS turning steel and a special development, a dreborid G-diamond wheel. Due to the low hardness of CBN compared to PCD, even inexperienced tool grinders were now able to regrind the cutting edge.

Encouraged by these first experiences and during our search for other possible applications, we were inspired by the positive experiences during the use of Borazon CBN grinding wheels.

Both procedures, grinding and turning, could handle materials like high-alloyed hardened steel with a hardness from 58 to 62 HRC. We realized that from now on, there would be a "gap" between grinding with CBN and machine with PCBN cutting materials despite continued attempts by tool manufacturers to counteract this tendency with newly developed types of carbides and ceramics.

The Alternative to Elbor

The readers will likely assume that the first successful attempts during hard machining were owed to the imported CBN cutting material named Elbor but with the initially worried about disadvantage. A solid-carbide basis for soldering was missing from the 8mm in diameter CBN compact unit.

More and more often, we ran into the problem that the "precious" Elbor cutting edge would break out of its matrix after 30 to 35 percent usage. There was no other alternative manufacturer of PCBN cutting edges. Until the end of 1975, when our PCD supplier, GE, surprisingly informed us that we could order polycrystalline "BZN-compact" boron nitride cutting edges with a carbide basis for soldering. Without hesitation, we switched to BZN-compact.

Apparently, this polycrystalline material had already been developed in the mid-1960s in order to offer it GE subsidiary Carboloy, which was not interested at the time and did not want to have anything to do with products "superior to carbide." That is how Louis Kapernaros (at the time general manager at GE Super Abrasives, Worthington, Ohio) described the situation years later when we had become very good friends.

The punch line in this regard: When we presented CBN tools at the Hanover Trade Show in 1975, Carboloy in Frankfurt had BZN inserts in its safe for some time. All told, once again the first step to the introduction of a new technology had been taken. Let's simply call it the "hour of the birth of hard turning."