Seven ways to avoid breaking taps

Seven ways to avoid breaking taps

Every machinist hates breaking taps. It's a real pain to extract a broken tap without damaging the part. But there are ways to reduce the number of broken taps shops have to deal with.

Every machinist hates breaking taps. It's a real pain to extract a broken tap without damaging the part. Plus, tapping always seems to be one of the last operations done on a part, which helps ensure the highest cost if you need to scrap the part. But seven things greatly will reduce the number of broken taps you have to deal with.

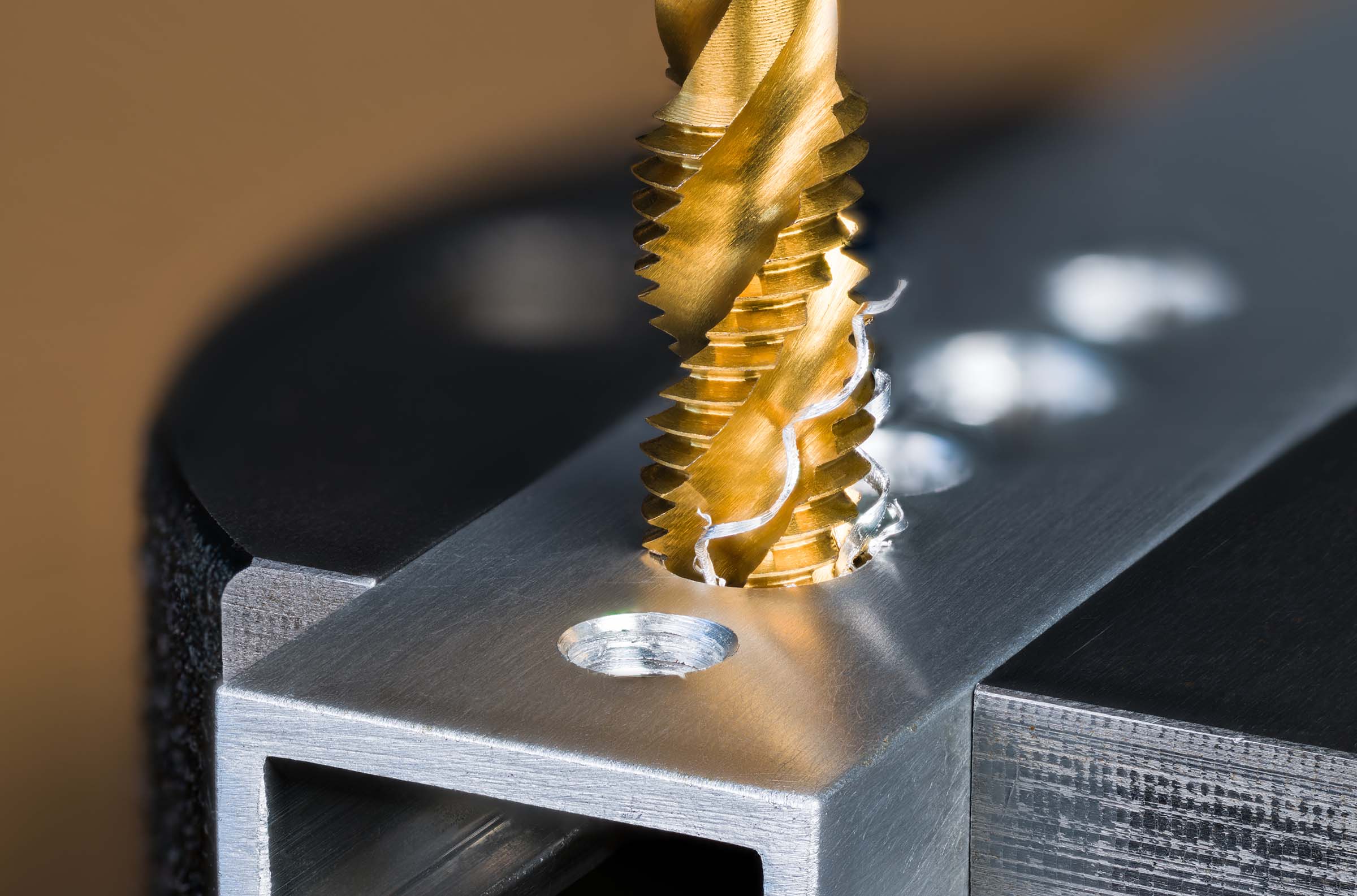

For machinists, there isn't much that is worse than breaking a tap. A Cutting Tool Engineering image

1. Choose the best hole size.

This is the tip that should make the biggest difference. Look, the recommended hole size found on the packaging for the tap or in your drill index probably is not the best size. It's important to realize that there is no single drill size for a tap. Different drill sizes result in different thread percentages.

Here's what is key: A 100% thread is only 5% stronger than a 75% thread but requires three times the torque. So for just a tiny bit stronger thread, you wind up with a much greater chance of breaking a tap.

The recommended drill size is almost always a 75% thread. That provides great strength but is well into the zone of too much torque.

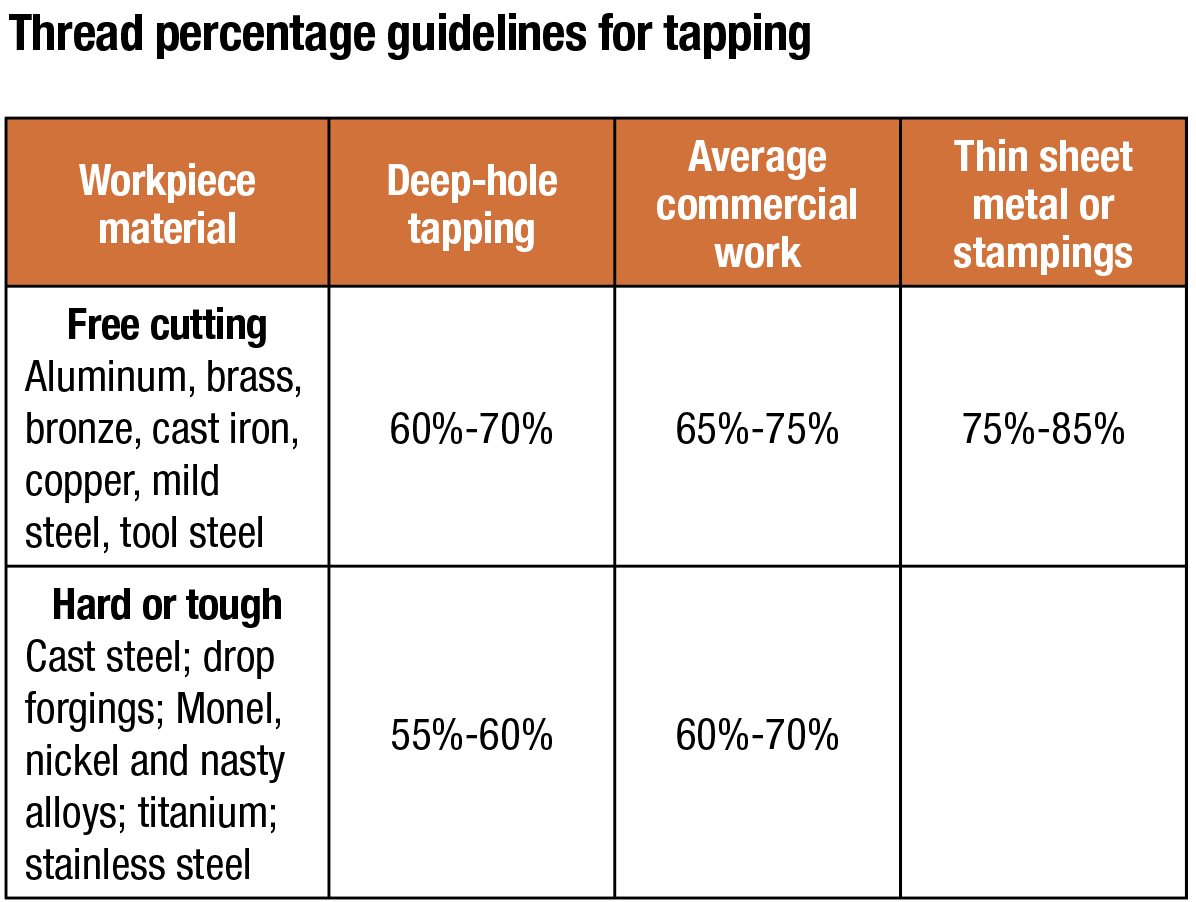

Thread percentage guidelines for tapping are based on different conditions. Image courtesy of B. Warfield

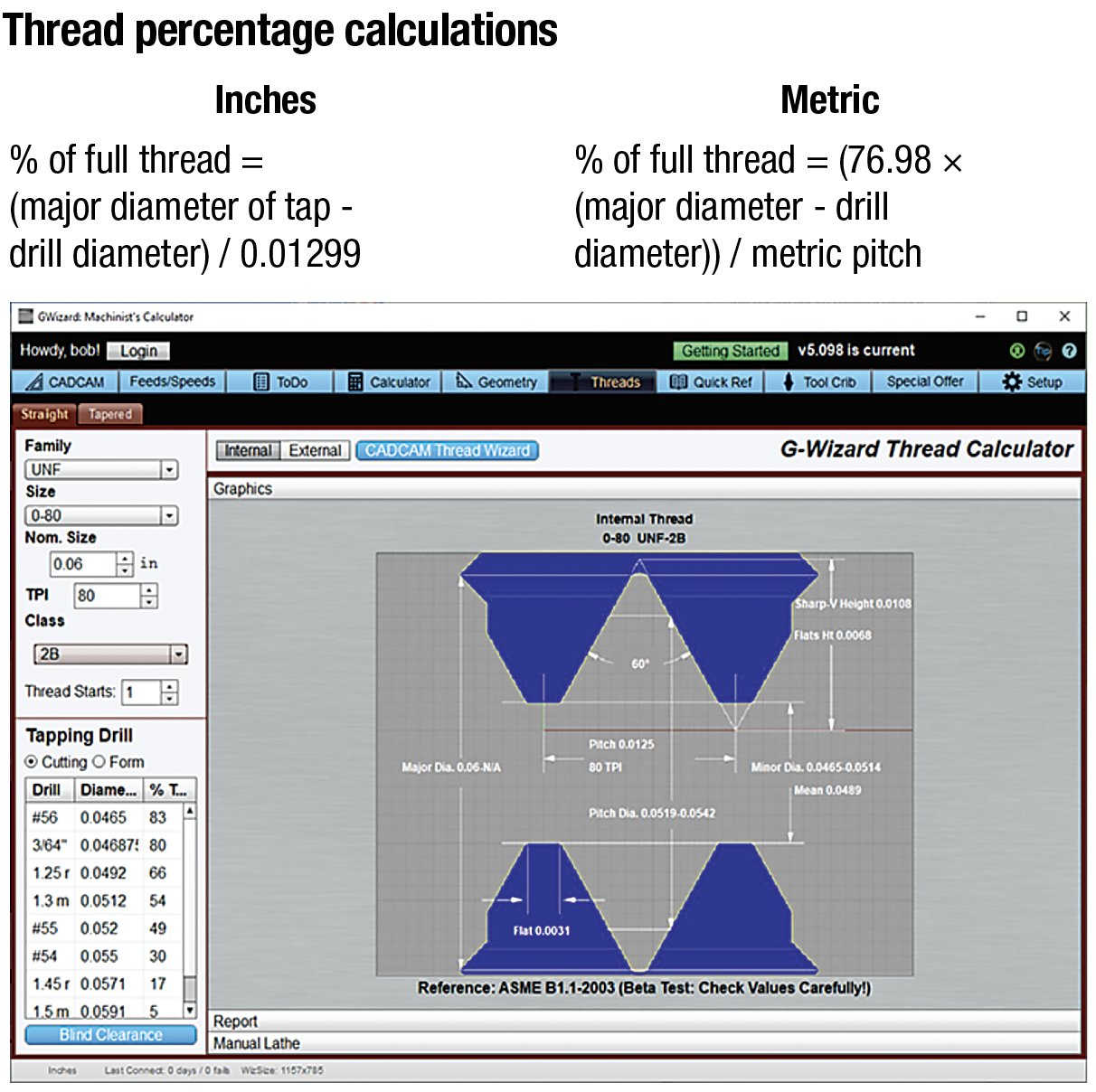

Calculating thread percentage is easy. Image courtesy of B. Warfield

The table about thread percentage guidelines for tapping gives advice based on different conditions. Dial back to less than 75% when tapping deep holes. Dial back for hard, tough materials too.

Make sure to check the requirements of the job. A customer may need a particular thread percentage. But if not or if the work is within the ranges in this table, back off the thread percentage, and your taps will thank you.

Calculating thread percentage is easy. The formulas are found in the figure about thread percentage calculations. Or you can use a handy tool like the G-Wizard machinist's calculator, which is pictured in the figure.

Use form taps whenever possible. Image courtesy of B. Warfield

2. Use form taps whenever possible.

They don't generate chips, and they push material into shape, cold forming the threads. The most common reason why taps break is because they become bound up in their own chips, which can't happen with a form tap. Form taps also have a greater cross section, so the taps themselves are stronger than cutting taps.

Form taps have two disadvantages. First, form taps can't be used on hard materials. You can form-tap materials up to only 36 HRC. That's a lot more materials than you might think, but there are definitely materials that can't be form-tapped. Second, some industries don't allow form taps because the process may create voids that trap contaminants on the threads. Form tapping also can result in stress risers on threads.

3. Always consider thread milling instead of tapping for critical or tough jobs.

Thread mills last longer than taps on a job, though thread mills do cut more slowly. You can thread closer to the bottom of a blind hole, and a single thread mill can cut a variety of thread sizes. Plus, thread mills can be used with harder materials than taps use. Thread mills may be the only option for materials over 50 HRC. Lastly, if you break a thread mill, it's smaller than the hole, so it won't become stuck in the part the way that a tap might.

4. Consider a purpose-made tapping lubricant.

Most machine coolants, especially water-soluble ones, are not as good for tapping. If you're having problems, try using special tapping lubricant. Put it in a spill-proof cup that sits on the machine table, and program the G code to automatically dip the tap in the cup. You also may try coated taps, which add lubricity through their coatings.

5. Use the right toolholder.

Let's talk about toolholders for tapping. To start, use a holder that locks the square shank on a tap so it can't twist in the holder. Tapping uses a lot of torque, so having a positive lock on that shank is helpful. You can do that with chucks made for taps or with special ER tapping collets.

Second, consider a floating holder even if your machine supports rigid tapping. Floating holders are a must without rigid tapping, but they increase tap life even in most rigid tapping situations. That is because machines are limited by the acceleration of spindles and axes on how closely machines can synchronize taps to the threads being made. There's always some axial force pushing or pulling. A floating holder relieves stress from the lack of perfect synchronization.

Use spiral-fluted taps when appropriate. A Cutting Tool Engineering image

6. Use spiral-fluted taps when appropriate.

If you're tapping a blind hole, failure to extract chips is the most common reason that taps are broken. That's why we use spiral-fluted taps. They eject chips up and out of a hole. Note that spiral-fluted taps are not as strong as the more common spiral-point taps, which is why spiral-fluted taps are not used all the time. Use them just for blind holes.

7. Mind the depth.

Speaking of blind holes, my seventh and last tip is to mind the depth on them. Crashing a tap into the bottom of a blind hole almost certainly will break the tap.Many people are not aware of this, but you can calculate how much clearance to leave at the bottom, and it's probably more than you'd think.Taken together, these seven tips should dramatically reduce the risk of breaking taps at a shop.

View a video presentation of this article at cteplus.delivr.com/2vb86