Freer Thinking

Freer Thinking

This article describes a self-contained micromachining center. The unit uses PC-based controls and a video system to machine small parts with precision, while giving the machinist a magnified view for setup and prototyping.

Several machine tool builders have taken root there over the past decade. These companies share at least one characteristic: They all specialize in finding creative solutions to known problems. Their work has earned the region a reputation as a source of innovative equipment.

Among these self-made Valley men stands Ed Freer, proprietor of Freer Engineering, Simi Valley, Calif. Ask Freer for credentials, and he points to a wall in the room next to his office. There, hanging in 13 frames, are the patents that attest to this inventor's creative use of technology in a number of disciplines. He has designed assembly machines for the electronics industry, a machine that inserts tips into ballpoint pens, and measuring equipment.

Freer's biggest contribution to metalworking is his micromachining center. Dubbed the SM-2000, the machine can be used to produce miniature parts in small lot sizes from a variety of difficult-to-machine materials (Figure 1). And once a shop is satisfied with the prototypes and short-run parts coming off the machine, the SM-2000 can shift into high gear to become an effective production machine.

Figure 1: The SM-200 uses PC-based controls ans a video system to aid in the manufacture of miniature parts. Inset: The SM-2000 can be used at every stage of prototyping and production for small parts such as these.

The SM-2000 grew out of Freer's efforts in the 1980s to design a machine for the fabrication of miniature medical parts. Some manufacturers make small parts with equipment such as screw machines, but these machines cannot produce a small run of parts economically. And a machining center might be used for short runs, but it does not offer a magnified view of the part for setup and prototyping work.

Freer's answer was the SM-2000. "I call it a smart machine because the computer has all the information required for the machine to work stored in its master file," Freer said. With such information close at hand, an operator can program an application simply by assembling individual operations from the blueprint.

Chief among the machine's problem-solving innovations is its PC-controlled video monitoring and inspection system. Freer's prior experience designing measuring equipment had taught him that users would accept viewing small parts with a video system much faster than they would take to any other type of technology.

"Nobody would take the time to learn how to use a microscope," he said.

Simplicity Designed In

In one departure from many other machines, Freer gave the SM-2000 PC-based controls with a standard library of functions already programmed and installed instead of a CNC. By calling up these functions, an operator can automatically execute any machining

operation without additional mathematics or machining instructions. The only data that must be input for each operation are the travel distance, the speed and the feed rate.

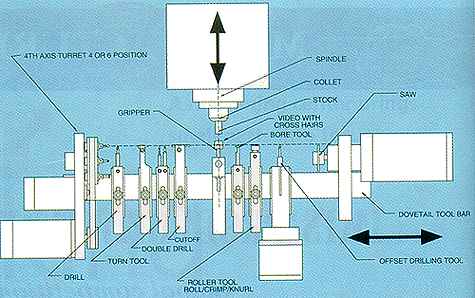

The operator uses conversational programming to enter this information at the machine, choosing from menu options such as "turn," "saw slot" or "cutoff." The SM-2000 is equipped with a drill, a turning tool, a double-drill, a cutoff tool, a boring tool, a roller tool, an offset-drilling tool and a saw (Figure 2). These are standard miniature carbide tools. With a combination of tools and programming, the machine can perform a wide variety of operations, including turning, drilling, milling, rolling, crimping, broaching, knurling and cutoff.

Figure 2: Among the operations the SM-2000 can perform are drilling, milling, turning, sawing, crimping and broaching. The machine comes equipped with all the standard miniature carbide tools shown.

With some relatively easy programming steps and a standard single-point cutting tool, an operator can even produce special, complex threads or knurl the inside diameter of a part. An auxiliary spindle on the 4th axis eliminates the need for many secondary operations.

The operator premounts the cutting tools inline on the machine. Once the tools are mounted, the operator assigns them positions so the computer will know the locations of their centerlines and edges. To locate each tool, the operator uses a joystick to move the table. With the tool aligned in the X-Y coordinate cross hairs on the video screen, the operator makes a few keystrokes to establish the tool's location in relation to the workpiece's centerline and its end. After all the tools' locations have been established, the operator enters the machining dimensions to create the tool paths. Each machining step is programmed in sequence.

To cut a thread, for instance, the operator first uses the menu to ask for the threading tool. Then he or she defines the thread dimensions and, finally, establishes the thread termination. Once the prototype program has been listed and tested, the machine is ready to operate automatically. The operator simply enters the number of parts to be produced and the machine becomes an automatic production center.

Simple Success

Among the users who value the SM-2000's uncomplicated operation is Rob Whitmore, president of Medical Micro Machining Inc., Simi Valley. "For short runs or prototyping, the SM-2000 is simple and easy to use compared to more complex machines like the Swiss automatics," he said. "The video screen makes it easy to see what you are doing at all times."

Whitmore claimed that he can train people with no machining experience to produce parts on the SM-2000 that an experienced operator would find impossible to produce on a standard CNC machine.

In Admore, Okla., the SM-2000 helped Imtec-Swiss Corp. earn the state's Innovator of the Year honor. The company's manufacturing engineer, Steve Hadwin, said the machine's ability to produce very small parts with a few simple programming steps proved invaluable. "Even a 0.060"-ID thread is no problem," he claimed, "and, most importantly, the video screen makes it easy to see parts as they're run."

Remmele Engineering, Big Lakes, Minn., uses the SM-2000 to shave time off of its prototyping schedule. For one prototyping project, the company was able to complete programming, setup and proof runs for four parts in three days. Typically, such a project would have taken a month to complete.

"Today, time to market is everything," said Dean Broberg, a Remmele manufacturing engineer. "With the SM-2000, we can turn out proof-of-concept parts in a day. This is a tremendous competitive advantage."

Ed Freer stands before the 13 patents he holds for machine designs. His inventions include assembly machines for the electronics industry, a machine that inserts tips into ballpoint pens, and measuring equipment.