Low-cost 3D printer for shop operations

Low-cost 3D printer for shop operations

A new breed of 3D printers has begun producing parts made of engineering-grade plastics and fully dense metals suitable for long-term use in a variety of applications. These include jet engine components, engine mounts, medical implants and a host of other products that were once machined or fabricated by conventional means. And, compared to earlier-generation machines, the new additive-manufacturing equipment offers enhanced part accuracy and has lower processing times and acquisition costs.

Service bureaus have 3D-printed prototypes and cores for investment castings since the introduction of commercial stereolithography machines in the mid-1980s. It wasn't long before product-design firms and large manufacturers began using these machines as well, speeding time to market and reducing development costs.

The MakerBot is a desktop 3D printer suitable for hobbyists and product designers alike. Image courtesy Stratasys.

Recently, though, a new breed of 3D printers has begun producing parts made of engineering-grade plastics and fully dense metals suitable for long-term use in a variety of applications. These include jet engine components, engine mounts, medical implants and a host of other products that were once machined or fabricated by conventional means. And, compared to earlier-generation machines, the new additive-manufacturing equipment offers enhanced part accuracy and has lower processing times and acquisition costs.

The latter points have piqued the interest of some job shops. Even though many don't plan to ever 3D-print parts for customers, there are still plenty of reasons to own a machine: to build low-cost fixtures, part-specific robotic part grippers, hands-on models for program prove-out and, that old standby, prototype parts.

With 3D-printer costs coming down, Ryan Sybrant, director of the manufacturing channel at Stratasys Corp., thinks it's time to take a look at them. The Eden Prairie, Minn., provider of 3D-printing equipment and services offers a range of systems, many suitable for one-off and low-volume production work.

"People are using 3D printing for an increasing number of projects around the shop," he said. "We're also seeing shops that will 3D-print a part for cost estimating and send the part to the customer along with the quote. It makes a nice impression, and, sometimes, identifies a problem in the part design the customer was unaware of."

In 2013, Stratasys acquired MakerBot, an entry-level machine for hobbyists. "I have one at home," Sybrant said. "It's a good machine for a shop that wants to get its feet wet with 3D printing or for educational purposes, but for general use around the shop or for making actual customer parts, I would probably recommend a professional FDM system."

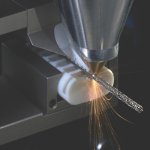

Sybrant said professional fused deposition modeling systems start at around $30,000, with the price based on machine size, the number of materials it can handle and processing speed. [Editor's note: Stratasys invented the FDM process.] They work by heating a filament of thermoplastic to its melting point, then setting down successive layers of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), nylon, polycarbonate and similar materials, building the part from the bottom up.

Part accuracy to ±0.0035" (±0.09mm) is possible, but this depends on part size, geometry and the machine model. "FDM printers produce durable, end-use parts and are quite easy to use," Sybrant said. "The technology lends itself well to a shop environment, with minimal maintenance and low operating costs."