Balancing digital manufacturing with advanced subtractive laser technology

Balancing digital manufacturing with advanced subtractive laser technology

The success of modern product development and manufacturing efforts depends increasingly on being able to iterate quickly, test innovative ideas and shorten time to market. Products must be designed, materials evaluated, prototypes tested and parts manufactured faster than ever. With access to the right technology, agile teams can quickly go from design to production, using less resources and meeting customer demand. A comprehensive rapid prototyping and manufacturing strategy offers an obvious advantage to businesses looking to keep their products and services competitive.

Article from Universal Laser Systems Inc.

The success of modern product development and manufacturing efforts depends increasingly on being able to iterate quickly, test innovative ideas and shorten time to market. Products must be designed, materials evaluated, prototypes tested and parts manufactured faster than ever. With access to the right technology, agile teams can quickly go from design to production, using less resources and meeting customer demand. A comprehensive rapid prototyping and manufacturing strategy offers an obvious advantage to businesses looking to keep their products and services competitive.

Although sophisticated and highly capable, additive manufacturing technologies are actually just one segment of rapid prototyping and manufacturing. Digital subtractive systems increase capability by offering complementary functionality with similar flexibility and speed. It is also worth noting that a large percentage of manufactured parts are made from flat raw materials.

When selecting a subtractive technology to work alongside additive manufacturing systems, it is essential that the system chosen is capable of matching the quality and performance of the 3D technology, working flexibly, accurately and efficiently. Investing in a technology that can be used on a wide range of materials and can quickly produce high quality parts, offers greater capability and speed within product development and manufacturing environments.

Advanced laser systems are a great example of a technology that fulfils these requirements. These systems can be used for precise machining, such as cutting, drilling, scoring and marking, almost any material in just seconds or minutes. David Richter of Universal Laser Systems summarizes the reasons why digital laser technology is an ideal complement to additive methods. "As product lifecycles get shorter, manufacturers in many industries are turning toward rapid subtractive technologies like laser cutting and marking systems. Traditional subtractive equipment is often associated with long lead times, due to the fixturing, programming or skilled labour required to operate each machine. This not only drives up cost for mid to low volume production runs, but also slows down prototype builds and testing. By comparison, these digitally-based, rapid-deployment tools can dramatically shorten time to market and decrease costs associated with design revisions."

It is important to understand however, that not all laser systems are equal. Some will claim multiple capabilities, but deliver lower overall performance levels, as they are not particularly optimised for any specific task. Therefore, the benefits highlighted here will only be fully realised if the laser system selected exhibits the characteristics of a truly advanced system capable of high performance and multiple processes.

Functionality, Precision and Speed – Essential Attributes

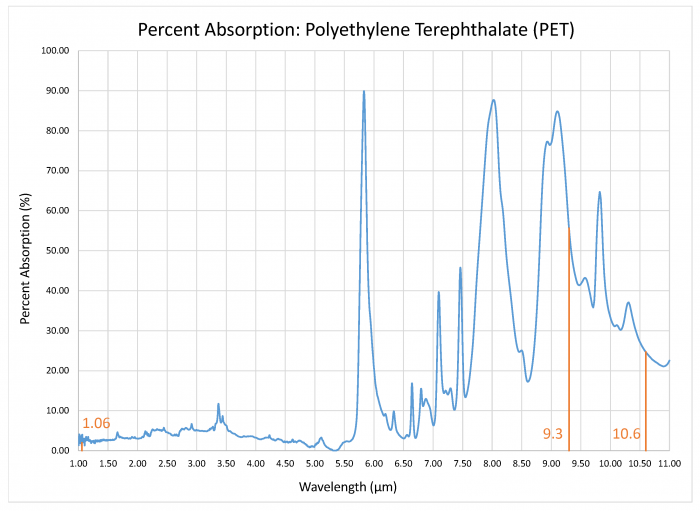

Investing in the right digital laser technology not only streamlines workflow, but also increases manufacturing flexibility. Advanced laser systems are able to process a wide range of materials by allowing users to select the ideal combination of power and wavelength for each application. The best choice or combination of CO2 or fiber laser source, power and wavelength(s) will of course vary depending on the material being processed, due to each material's optical wavelength absorption characteristics. In the example of PET below, a laser wavelength of 9.3 µm (CO2) is more easily absorbed than 10.6 (CO2) or 1.06 µm (fiber).

PET optical absorbance of laser energy is higher using a 9.3 µm wavelength over 10.6 and 1.06 µm.

Today, product designers, engineers and manufacturers alike demand high quality and finish even on prototype parts. Achieving these objectives requires laser technology with precise energy delivery. This is accomplished through advanced motion path planning, micron level beam positioning and by giving users the ability to fine tune the laser output to their application. Adjustable laser settings such as wavelength, power, speed, duty-cycle and pulses per inch (PPI) allow the user to calibrate the process to their specific material application.

However, if users are to obtain the full potential offered by advanced laser systems, then the process of selecting the parameters or configuration required for a specific material must be kept as simple and robust as possible. Providing the user with a selection of pre-programmed parameters and settings, tested and proven through extensive research by the laser manufacturer, both simplifies this process and significantly reduces the time required to manufacture parts. Having access to a comprehensive database of materials knowledge and configuration settings makes it possible to successfully process the widest range of materials with the highest levels of precision and repeatability.

In addition to providing quality repeatable results, advanced laser systems are highly efficient. As a digital technology, setup and workflow are immediately simplified. However, throughput and quality can be further improved through high processing speed, advanced path planning and features such as beam autofocus. The relationship between laser beam focal point and the work piece surface greatly influences performance and quality. Using a high precision motorized focus assembly, with a high-resolution touch sensor, ensures that regardless of material, the correct focal distance will always be achieved. This valuable feature operates seamlessly with the many components that are still manufactured from flat raw materials, and where advanced subtractive laser technology delivers its greatest benefits.

Achieving and maintaining geometric integrity of components, whilst ensuring that the finished part correlates to the original design file, requires micron level beam positioning and advanced motion path planning. This ensures that shapes or profiles such as circles, ellipses and curves are actually produced as true curves and not as a series of small, segmented, linear interpolations. Combine this functionality with the ability to control laser pulses at specific locations and both process accuracy and consistency are further enhanced. Today's manufacturing environment requires ever-greater levels of connectivity; both from a digital and physical perspective, as increasing numbers of processes are linked together.

An advanced laser system with the capability to receive input signals from a PLC to initiate laser system functions, and also control external devices using digital output signals, makes it possible to easily integrate the laser system within an automated manufacturing environment. Combine this functionality with a robust and intuitive interface and users can realise the maximum potential for either stand-alone or integrated operation.

Selecting a subtractive laser technology with flexibility, precision and speed will deliver excellent processing results on a wide range of materials. Richter sums up: "It's clear that having the right subtractive laser technology available alongside additive systems boosts productivity and opens up new possibilities. The ability to streamline digital workflow and quickly produce high quality components maximises manufacturing capability in a way that can only complement additive technology."

Incorporating advanced subtractive laser technology as part of a broader rapid manufacturing strategy will help product development and manufacturing teams continue to increase output and stay ahead of the curve.