AMT’s latest Global Forecasting & Manufacturing Conference found reasons for both caution and optimism.

To paraphrase the late singer/poet Jim Morrison, the end may not always be near but the future is definitely uncertain. However, the 2 days of expert industry information presented at the 2012 Global Forecasting & Marketing Conference revealed likely scenarios for where manufacturing is heading. Hosted by AMT – The Association for Manufacturing Technology, the conference took place Oct. 24-25 at the Hyatt Regency St. Louis at The Arch.

The recovery in manufacturing has helped lead the U.S. out of recession, but some caution signs are flashing. For example, in November, the Institute for Supply Management’s manufacturing index fell to 49.5 from 51.7, its fourth month in the last six below the breakeven 50 mark.

Ian Stringer, business intelligence manager for AMT

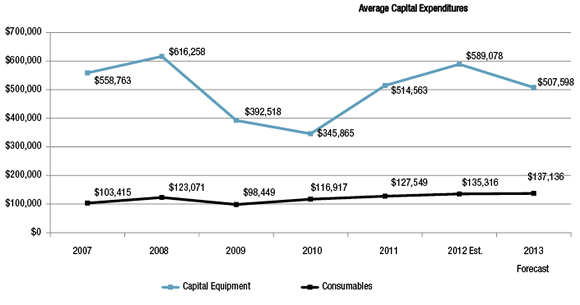

A presentation by Ian Stringer, business intelligence manager for AMT, seemed to echo that caution. Stringer presented the results of the 2012 Job Shop Capital Spending Survey by the National Tooling & Machining Association. The key finding was that average capital expenditures in 2013 per U.S. job shop are expected to drop to $507,598 (see graph below), down 13.8 percent from 2012, when they were expected to be $589,078. That’s still well above the recent low of $345,865 in 2010, but shows some pullback from the heady expansion experienced in 2011 and 2012.

Working Abroad

Still, U.S. manufacturers are coming off several solid years of growth, and one of the growth drivers is the export market. Those who follow the export route to growth need to develop the courage to compete—and win. That was the theme of an AMT member panel at the conference, which included presentations by James L. Vosmik, president/owner of Drake Manufacturing Services Co., Warren, Ohio; Steven G. Harris, president and CEO of Micro-Poise Measurement Systems LLC, Streetsboro, Ohio; and Glen A. “Fritz” Carlson III, president/owner of Acme Manufacturing Co., Auburn Hills, Mich.

James L. Vosmik, president/owner of Drake Manufacturing Services Co.

Vosmik noted Drake started exporting in 2000 to avoid boom-to-bust cyclicality because it is rare that all markets are down at the same time and most of the global market is outside NAFTA, meaning Mexico and Canada are “home” markets. Exporting begins with being able to manufacture something someone will pay for, he said. “But, guess what, they do not beat a path to your door no matter how good the mousetrap is,” he said.

Courtesy of National Tooling & Machining Association

Capital equipment and tooling expenditures per individual job shop.

The courage to compete starts with knowing your product and its value to foreign markets, while the discipline to compete begins with the ability to say “no, thank you” to irrelevant opportunities, Vosmik added. He recommends creating a stop-doing list instead of a to-do list, as well as “getting the wrong people off the bus” and resisting the urge to chase numbers.

Harris emphasized the need to be there in person for all phases, including meeting sales representatives, prospects and customers, and to continue that effort. “Relationships have to be at the highest levels,” he said. The big- gest barrier to success in BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) markets is finding trustworthy local partners, staff and suppliers, Harris added.

Steven G. Harris, president and CEO of Micro-Poise Measurement Systems LLC

Particularly when exporting to Brazil, Carlson stressed the importance of having a local logistics person to help pull machinery through customs rather than trying to push it through from the U.S.

Because a country’s culture greatly influences the sales process, Harris recommends learning about the culture and accepting cultural differences.

In addition, Harris noted it’s critical to sell on value and not on price because the competition in foreign markets will include low-cost ones.

Glen A. “Fritz” Carlson III, president/owner of Acme Manufacturing Co.

However, Carlson pointed out that manufacturers may have to develop or alter equipment for a particular market. This might involve eliminating some of the bells and whistles to reduce the cost or better suit the worker skill level in that market.

Carlson noted Acme Manufacturing sells to 10 overseas markets and serves 15 different industries. “Have as many lines in the water as you can,” he said. “If you don’t pursue international business, there are opportunities passing you by every day and you don’t even know it!”

Pump Up the Mileage

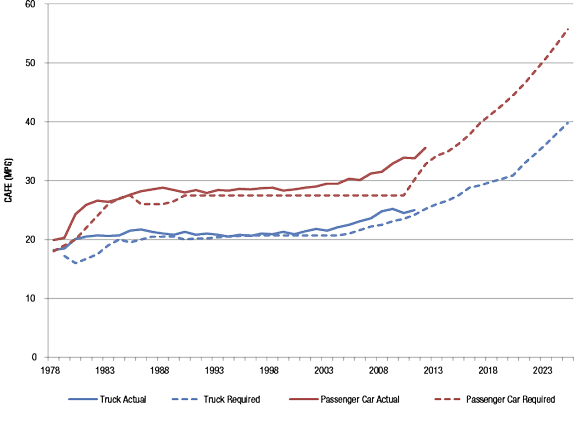

Traditional markets continue to drive the manufacturing industry, and the automotive industry is a prime example. One of the trends driving renewed investment in new parts and processes is fuel economy, brought on by the U.S. government reaching an agreement with 13 automakers to deliver 54.5-average-mpg passenger cars by 2025. Brett C. Smith, co-director of manufacturing, engineering and technology for the Center for Automotive Research (CAR), Ann Arbor, Mich., gave a presentation about power train manufacturing technology to meet those regulations.

Brett C. Smith, co-director of manufacturing, engineering and technology for the Center for Automotive Research.

“CAFE (Corporate Average Fuel Economy) will change the normal but not as dramatically as feared,” he said, noting the regulations will be reviewed in about 5 years to see if they are achievable. “The power train that was low tech/low precision, is now high tech/high precision and goes to very high precision with the new regulations.”

Smith pointed out that the 2025 estimated CAFE for passenger cars varies for each manufacturer based on its fleetwide average wheelbase. For example, the compact Honda Fit has a 40-sq.-ft. footprint, a 30-mpg 2012 EPA rating and a 61.1-mpg 2025 target, and the full-size Chrysler 300 has a 53-sq.-ft. footprint, a 21-mpg 2012 EPA rating and a 48-mpg 2025 target. Fleetwide, Chrysler moves from a 2011 model year CAFE of 29.9 mpg to 55.6 mpg in 2025 while Honda goes from 36.0 mpg in 2011 to 57.0 mpg in 2025. However, the real-world estimate, the figure a consumer sees on a vehicle’s window sticker, is 80 percent of the target.

Light-duty truck regulations are lower, at just over 40 mpg, but may be harder to meet, according to Smith. “You may need an aluminum-intensive truck,” he said.

One way to improve fuel economy is to reduce vehicle mass, and the Department of Energy’s goal is a 10 percent weight reduction for the power train by 2020 and a 20 percent reduction by 2025. A 20 percent reduction for the complete vehicle will be required by 2020 and a 30 percent reduction by 2025. However, the mass of U.S. passenger cars has been trending up since the late 1980s, primarily because of the increase in comfort and convenience accessories.

Smith said the first step to downsize the engine is gas direct-injection technology “to make it act like a diesel,” which is used in Europe and Japan for efficiency and performance. Other mass reduction technologies for internal combustion engines include turbochargers, superchargers and cylinder deactivation.

Courtesy of EPA/NHTSA

Actual and regulation miles per gallon for passenger cars and light trucks.

Because of their enhanced fuel efficiency, automakers are looking to increase production of electric vehicles. According to Smith, types of vehicle electrification include motor assist (GM E-Assist), hybrid EV (Honda Insight), plug-in hybrid EV (Toyota Prius Plug-in), extended-range EV (Fisker Karma) and battery EV (Nissan Leaf). “Everything learned about EVs is from the fundamental hybrid vehicle,” Smith said.

Nonetheless, all those types of EVs represent only about 3 percent of the vehicles on the road, and those EVs are having a tough time, Smith noted. Consumer Reports stated the Karma is “plagued with problems,” Nissan set up an “independent” probe of Leaf battery complaints and users are experiencing difficulties with the Prius Plug-in.

“The current capabilities of electric vehicles do not meet society’s needs, whether it is the distance the cars can run or the costs or how long it takes to charge,” said Takeshi Uchiymada, Toyota vice chair.

“It all comes down to battery technology,” Smith said, “and we don’t expect a breakthrough by 2025.”

Up, Up and Away

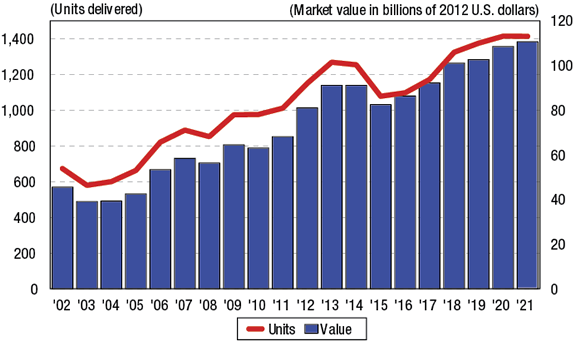

Of course, fuel efficiency is also a significant issue for the aviation industry, which Richard L. Aboulafia, vice president, analysis for Teal Group Corp., Fairfax, Va., called “the best functioning manufacturing business on the planet” during his presentation titled “Outperforming the Economy: Aerospace and Defense Market Outlook.”

He noted fuel burn is a major factor for the industry in this “age of permanently expensive fuel,” and airlines want the new, more fuel-efficient planes to save on fuel costs.

Richard L. Aboulafia, vice president, analysis for Teal Group Corp.

Courtesy of Teal Group

Commercial jetliner history and forecast.

Aviation, which is dominated by Boeing and Airbus with a combined 55 percent of the output, “powered its way through the last downturn with no cycle impact,” Aboulafia said. Worldwide deliveries of large jetliners expanded 21.7 percent from 2008 to 2011.

A primary reason is the attractiveness of leasing and financing jetliners. “It’s hard to lose money there, and is the closest thing to a secure investment for now,” he said, noting global airline net profit in 2012 was $11 billion. “There’s a vast pile of cheap cash looking for a home and there are few options. Jetliners are like U.S. government debt—a safe place to land cash.”

On the other hand, cargo traffic is a concern and not doing so well because “people are skittish about global trade,” Aboulafia said. He added the BRIC nations are performing adequately, but there are worries about Brazil and India.

The regional airplane market is also tough, with a worldwide delivery drop of 27.3 percent from 2008 to 2011. “But Embraer is making a pretty good go of it,” Aboulafia said. “Large regional jets are the flavor of the moment but I can’t guarantee that will continue.”

Mergers are “killing regionals,” he said, because that means there are fewer airport hubs to feed.

Business aircraft sales are also down, falling 28.4 percent from 2008 to 2011. According to Aboulafia, business jets are highly specific products, third-party financed and tough to repossess. “If the Euro zone cleans up its act and the ‘fiscal cliff’ is avoided, replacement cycles for business jets will kick in, possibly in 2014,” he said.

Aboulafia predicted sequestration, or the fiscal cliff, won’t occur, with continuing resolution the likely outcome.

With lots of speculative money being thrown at large jets, a hard landing “could be ugly,” he warned. That would occur if economic and traffic growth falls or fails to grow fast enough, fuel becomes less costly, plane program delays occur, interest rates rise and key financial market enablers get burned by falling lease rates and values. “If fuel gets cheap, they won’t need two-thirds of these jets,” Aboulafia said. “Then, a fully paid-off jet with less efficiency is more attractive.”

His industry forecast, however, is for a soft landing, with a bit of a dip in 2014 to 2015 before rising again. In addition, Aboulafia projects a compound annual growth rate of 3.6 percent from 2012 to 2017 for the total aircraft market—“no bust, less boom.”

The 2013 AMT conference takes place Oct. 15-16 at the Hyatt Regency Cincinnati. For more information, visit www.amtonline.org/gfmc. CTE

The 2013 AMT conference takes place Oct. 15-16 at the Hyatt Regency Cincinnati. For more information, visit www.amtonline.org/gfmc. CTE

About the Author: Alan Richter is editor of CTE. He joined the publication in 2000. Contact him at (847) 714-0175 or [email protected].

Sweet results from sour, corrosive application

As the characteristics of oil wells change, and with the number of deep wells growing for deep-sea drilling and hydraulic fracturing in comparison to shallow wells, more part manufacturers are making components from heat-resistant superalloys, such as Inconel 625 and 718.

This is because unlike the mildly corrosive “sweet” crude found in shallow wells, deep wells contain “sour” crude, which is highly corrosive because of its sulfur content. HRSAs can withstand that environment. In addition, parts for fracking equipment are used at depths of 7 miles or more and experience pressures up to 25,000 psi and temperatures as high as 500° F.

As a result, more HRSA materials are being used. A presentation at the AMT conference by Bill Tisdall, product development and turning manager for Sandvik Coromant Co., Fair Lawn, N.J., focused on how to profitably machine HRSAs.

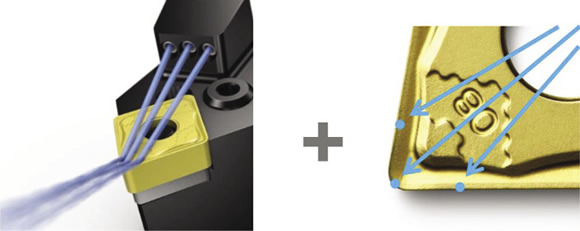

Courtesy of Sandvik Coromant

When applying high-pressure coolant, some insert geometries direct coolant to the cutting zone.

Although superalloys resist pitting and sulfide corrosion cracking, the nickel and cobalt alloying elements make the machinability of HRSAs about 25 percent that of steel, such as 4140, he noted, adding that users switch to counting standard cutting edges per part and not parts per edge. Thin walls and complex component geometry for these applications only add to the machining challenge—and expense.

Nonetheless, HRSA part makers can optimize machining. One way is to apply inserts with a lead angle, whenever possible, because chips become thinner and elongated as the angle increases, redistributing cutting forces and protecting against notch wear, Tisdall explained. The result is longer tool life combined with the ability to increase feeds “a couple of thousandths.”

When applying round inserts, the lead angle is based on the DOC. The round shape provides strength but is unable to impart the finest surface finishes, so button inserts are only suitable for roughing nickel-base superalloys, according to Tisdall.

To minimize the need for engineered specials for effectively cutting complex features, Tisdall recommends modular tools. In addition to reducing tool costs, modular tools eliminate stocking extra specials to avoid long lead times in case a tool breaks. “Rethink the way to attack the job,” he said.

Applying high-pressure coolant (1,000 psi and higher) is another possible route to boost productivity and tool life when cutting HRSAs. Tisdall pointed out, however, that high-pressure pumps aren’t enough and cutting tools designed to direct coolant to the tool/workpiece interface and create a coolant wedge are needed. HRSAs tend to generate stringy chips and the coolant wedge helps with chip control while reducing edge notching. In addition, inserts with geometries that help get the coolant to the cutting zone are available.

The final optimization area covered was programming techniques. These include the roll-on technique when milling and trochoidal milling. In contrast to a full feed directly into the workpiece, the roll-on technique uses a clockwise motion of the cutter to slowly engage it with the part, extending tool life and thereby reducing the time needed to change or index inserts.

A trochoidal toolpath reduces cutting forces and heat buildup in the chips. “It’s not a faster method,” Tisdall said. “It’s a smarter and more predictable way.”

—A. Richter

Contributors

Acme Manufacturing Co.

(248) 393-7300

www.acmemfg.com

AMT—The Association For Manufacturing Technology

(800) 524-0475

www.amtonline.org

Center for Automotive Research

(734) 662-1287

www.cargroup.org

Drake Manufacturing Services Co.

(330) 847-7291

www.drakemfg.com

Micro-Poise Measurement Systems LLC

(800) 428-3812

www.micropoise.com

Sandvik Coromant Co.

(800) SANDVIK

www.sandvik.coromant.com/us

Teal Group Corp.

(888) 994-8325

www.tealgroup.com

SaveSave

Related Glossary Terms

- arbor

arbor

Shaft used for rotary support in machining applications. In grinding, the spindle for mounting the wheel; in milling and other cutting operations, the shaft for mounting the cutter.

- coolant

coolant

Fluid that reduces temperature buildup at the tool/workpiece interface during machining. Normally takes the form of a liquid such as soluble or chemical mixtures (semisynthetic, synthetic) but can be pressurized air or other gas. Because of water’s ability to absorb great quantities of heat, it is widely used as a coolant and vehicle for various cutting compounds, with the water-to-compound ratio varying with the machining task. See cutting fluid; semisynthetic cutting fluid; soluble-oil cutting fluid; synthetic cutting fluid.

- feed

feed

Rate of change of position of the tool as a whole, relative to the workpiece while cutting.

- gang cutting ( milling)

gang cutting ( milling)

Machining with several cutters mounted on a single arbor, generally for simultaneous cutting.

- land

land

Part of the tool body that remains after the flutes are cut.

- lead angle

lead angle

Angle between the side-cutting edge and the projected side of the tool shank or holder, which leads the cutting tool into the workpiece.

- machinability

machinability

The relative ease of machining metals and alloys.

- milling

milling

Machining operation in which metal or other material is removed by applying power to a rotating cutter. In vertical milling, the cutting tool is mounted vertically on the spindle. In horizontal milling, the cutting tool is mounted horizontally, either directly on the spindle or on an arbor. Horizontal milling is further broken down into conventional milling, where the cutter rotates opposite the direction of feed, or “up” into the workpiece; and climb milling, where the cutter rotates in the direction of feed, or “down” into the workpiece. Milling operations include plane or surface milling, endmilling, facemilling, angle milling, form milling and profiling.

- pitting

pitting

Localized corrosion of a metal surface, confined to a point or small area, that takes the form of cavities.

- recovery

recovery

Reduction or removal of workhardening effects, without motion of large-angle grain boundaries.

- superalloys

superalloys

Tough, difficult-to-machine alloys; includes Hastelloy, Inconel and Monel. Many are nickel-base metals.

- toolpath( cutter path)

toolpath( cutter path)

2-D or 3-D path generated by program code or a CAM system and followed by tool when machining a part.

- turning

turning

Workpiece is held in a chuck, mounted on a face plate or secured between centers and rotated while a cutting tool, normally a single-point tool, is fed into it along its periphery or across its end or face. Takes the form of straight turning (cutting along the periphery of the workpiece); taper turning (creating a taper); step turning (turning different-size diameters on the same work); chamfering (beveling an edge or shoulder); facing (cutting on an end); turning threads (usually external but can be internal); roughing (high-volume metal removal); and finishing (final light cuts). Performed on lathes, turning centers, chucking machines, automatic screw machines and similar machines.