Tired of your wimpy 5C indexer or NC rotary table giving up its position faster than a politician after an election? Maybe it’s time to supersize that commodity indexer. Doing so will produce more parts in less time, with better part quality to boot.

Lee Flick, vice president at workholding supplier Pioneer N.A., Elk Grove Village, Ill., said successful machining on an indexer is all about clamping torque. “Many of our customers come to us after they’ve purchased an inexpensive indexer elsewhere. They mount it to their machine and start cutting as if the part was clamped directly to the machine table, then have to back off when the indexer starts moving on them.”

According to Flick, higher clamping torque allows shops to machine at a more efficient rate, often doubling or tripling output. Better yet, the 33 percent cost delta between a ho-hum 8 " indexer at $15,000 and one for $20,000 that hits a home run each time at bat is not that great. “The extra investment will give you over 400 ft. lbs. of clamping torque, roughly four times that of a low-cost table,” he said.

Maybe that doesn’t matter if all the jobs involve light-duty machining close to the centerline of the table, where cutting forces have little leverage, but that’s rarely the case. “The majority of machining in the U.S. is done in job shops,” Flick said. “One day they’ll mount a 50-lb. workpiece on an indexer and hog with a 1 " rougher, the next day load up a four-sided tombstone with 10 parts per side and let it run for hours unattended. You need an indexer that can handle whatever you throw at it.”

If a rotary table shifts during machining, it can result in broken cutters and scrapped parts. How that indexer gets into position, however, is just as important as holding it there once it arrives. Chris Salamone, sales manager for Ramsey, N.J.-based Indexing Technologies Inc., explained two drive mechanisms are available for most rotary tables and indexers.

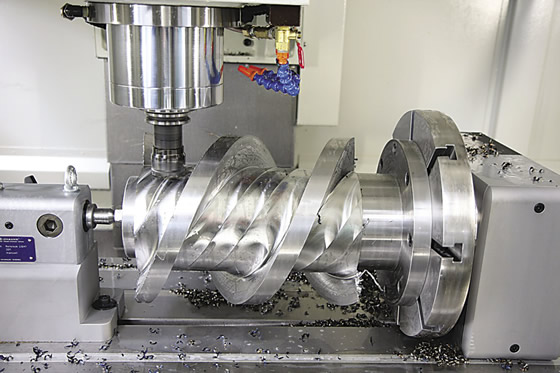

A Lehmann EA-510 rotary table performs 4-axis machining of an aluminum drive screw mounted to a faceplate.

“Worm and wheel drives have long been the conventional power transmission method for rotary tables,” Salamone said. “They use a worm screw driving against a gear wheel to translate the rotation of the servomotor into rotary positioning of the indexing table.”

The downside—as in most gear-driven mechanical systems—is backlash. Yet Salamone explained that a well-built worm wheel works perfectly for the majority of applications, providing accuracy to better than 3 arc seconds when contouring and positioning.

The second method is direct drive, or torque motor table, which is sort of like mounting a workpiece directly to the rotor of a high-torque servomotor. The result is fast and continuous rotation—several hundred rpm is not uncommon—and zero backlash. Salamone said torque motor tables account for 30 percent of new table orders. “You see them used a lot in grinding applications, where a shop needs to spin the workpiece at high rpm for a journal grind, for example, then index to fixed positions for secondary operations.”

According to Salamone, proper selection of indexers and rotary tables is application-specific. Large workpieces and multipart fixtures require an appropriately sized table, one that can support high radial loads. As indicated earlier, heavy cutting means you’d better have plenty of braking power. When contouring, you’ll need a motor strong enough to accurately rotate the workpiece, but still resist deflection from cutting forces.

Above all, you might need some advice. Ivo Straessle, owner of Rotec Tools Ltd., Mahopac, N.Y., said motor and table size, positioning accuracy and braking torque should be considered before purchasing a new indexer. Most importantly, decide if rotating the table while simultaneously cutting the workpiece—using 4th and 5th axes—will be necessary now or in the future.

Straessle recommends having the builder supply the drives and cabling for the 4th and 5th axes, so all a shop has to do is plug in the rotary table. Doing all this after the machine has been delivered may cost upwards of $15,000 and a day or more of downtime, roughly 50 percent more than the price of ordering it up front. This is good advice, but Straessle said roughly 80 percent of all applications only require indexing. “That means position the table, clamp it in place and start machining. As long as there’s enough braking power to keep the table in place, you’re good to go.”

A twin rotary table set up with trunnion fixtures from Tsudakoma.

Indexing capability can be the goose that laid the golden egg for many shops. Loading a tombstone or trunnion-style table with dozens of parts offers horizontal-machining-center capability at a vertical price. “If you can increase the number of parts and are able to hit more sides, you reduce your setups and have longer run times. Your operator can be off doing something else while the machine is making parts,” said John Arnestad, tooling manager for East Windsor, Conn.-based Koma Precision Inc.

Here again, braking pressure is critical. Because a tombstone setup often means working off center, the leverage exerted by cutting forces is drastically increased. A high-quality table with enough oomph to prevent table movement is required. It’s also advisable to have a locking support spindle on the other end, an option especially important with long or heavy tombstones—a rule of thumb is to avoid more than 2:1 overhang in the absence of a tailstock or trunnion-style support.

“People try to save money by going to less-expensive rotary products and accessories, but they’re not looking at the big picture,” Arnestad said. “Higher clamping force means you can push the cutters harder without fear of table slip. You can manufacture more parts per shift, consequently lowering part cost and increasing profit.”

Lastly, look at setup time. Even compact indexers are bulky—unless you have Schwarzenegger-like biceps, you won’t be lifting one into the machine without mechanical help. Get the hoist, maneuver the indexer into place, bolt it down, hook it up, dial in the face and find center, at the end of which at least 1 hour is gone, maybe two. Paul Kieta, national sales manager for the workholding solutions group at Cleveland-based tooling manufacturer Jergens Inc. has a better idea.

“Indexers are usually positioned off to the side of the table and left there,” he said. “Shops don’t take them off because of the large amount of time it takes to get them repositioned. We recommend using a zero-point or ball-lock system with a subplate. This provides the flexibility to quickly remove the indexer when other work comes along. The next time you need it, just drop the subplate into place and you’ll be in position within ±0.0005 " or better.”

For a relatively small investment, indexers and NC rotary tables provide shops with huge flexibility, but do your homework before signing on the dotted line. Buy one with enough braking pressure to do the job. Fixture it so you don’t waste time on setup. And if you think you’ll ever do 4- or 5-axis work, plan accordingly when ordering the machine. CTE

About the Author: Kip Hanson is a contributing editor for CTE. Contact him at (520) 548-7328 or [email protected].

Related Glossary Terms

- backlash

backlash

Reaction in dynamic motion systems where potential energy that was created while the object was in motion is released when the object stops. Release of this potential energy or inertia causes the device to quickly snap backward relative to the last direction of motion. Backlash can cause a system’s final resting position to be different from what was intended and from where the control system intended to stop the device.

- fixture

fixture

Device, often made in-house, that holds a specific workpiece. See jig; modular fixturing.

- grinding

grinding

Machining operation in which material is removed from the workpiece by a powered abrasive wheel, stone, belt, paste, sheet, compound, slurry, etc. Takes various forms: surface grinding (creates flat and/or squared surfaces); cylindrical grinding (for external cylindrical and tapered shapes, fillets, undercuts, etc.); centerless grinding; chamfering; thread and form grinding; tool and cutter grinding; offhand grinding; lapping and polishing (grinding with extremely fine grits to create ultrasmooth surfaces); honing; and disc grinding.

- numerical control ( NC)

numerical control ( NC)

Any controlled equipment that allows an operator to program its movement by entering a series of coded numbers and symbols. See CNC, computer numerical control; DNC, direct numerical control.