Slackers. Hackers. Disaffected, disenfranchised and disinterested.

Such are the unflattering labels applied to Generation X, that group of roughly 45 million individuals born between 1964 and 1977 who are making their presence felt in U.S. industries, including the manufacturing sector.

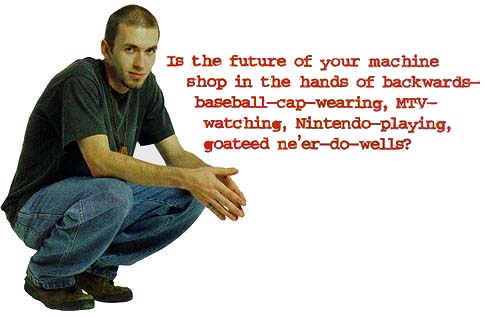

Do the stereotypes fit? Is the future of your machine shop in the hands of backwards-baseball-cap-wearing, MTV-watching, Nintendo-playing, goateed ne’er-do-wells?

Hardly. In fact, with respect to working in a modern machine shop, a number of owners and managers say that their recent Gen X hires are the best-qualified employees they have.

“They’re computer-savvy and not intimidated by new technology,” said Dave Krisovitch, general manager of Micro Tool Co. Inc., a Bethlehem, Pa., shop that specializes in complex prototype-to-production work produced on robotic-assisted CNC equipment. Krisovitch added that Gen Xers aren’t afraid of trying a new approach to a job.

It’s easy to understand why. The machinists, programmers and trainees who began hitting the shop floor several years ago are the first generation of Americans raised on interactive video games and home computers. A kid who grew up in the early ’80s as an Atari-playing “Master of the Universe” doesn’t have to stretch too far to learn the ins and outs of today’s conversational controllers.

But let’s not oversimplify. Obviously, running a $100,000 CNC machine tool isn’t the same as playing a game of Mario Brothers. And just as obviously, being comfortable around computers isn’t the only thing that distinguishes Gen X from earlier generations.

“I think that we’re motivated by different things than [other] generations,” said a 20-something CNC programmer named Pete. When asked to elaborate, he exhibited another Gen X characteristic—candor. “It seems like a lot of yuppies picked their jobs on the basis of money only, whether they enjoyed the job or not. My generation is interested in fulfillment first and money second.”

Though difficult to prove statistically, this philosophy seems prevalent among the machinists and programmers interviewed for this article. And it jibes with the experiences of a toolroom engineer/manager at a major packaging manufacturer. He recently lost a number of young machinists and engineers to other employers, not because of greater compensation or benefits, he explained, “but because they found something they wanted to do more—even if it was for less money.”

Gen Xers recognize that with trade skills of every type in critically short supply, they can shop around until they find an employer who offers more than just a paycheck.

“When I graduated from vo-tech, three different shops recruited me as an entry-level CNC programmer,” said Pete, who works in that capacity at a midsize job shop in the Northeast that’s packed with the latest CNC machine tools. “I picked this place because it seemed more progressive than others.”

Good and Bad

In assessing the strengths and weaknesses of Generation X machinists and programmers, the manufacturing manager at a Fortune 500 company said, “The good thing is that these kids have an unprecedented head start on previous generations. They’re better prepared for the rapid pace of technology, they’re more worldly and, in many cases, they can simply produce more work for less money than their older counterparts.”

And the bad? “They seem to have absolutely no sense of loyalty to their employer and no expectation of loyalty from their employer,” he continued. “They want everything now, and if they don’t get it, they have no reservations about moving on to get what they want somewhere else.”

Several other shop managers criticized Gen Xers for their lack of math and communication skills. These supervisors also mentioned that even though younger hires are highly motivated, they don’t respond well to the crises that regularly occur in the highly fluid contract machining industry.

“That’s because they haven’t seen any real adversity in their lifetime,” said one machine shop owner. “Compared to the World War II generation, for example, these kids have no idea what the word ‘adversity’ means. With some of these guys, a broken tool is a catastrophe.”

The plant engineer at Phoenix Tube Co. Inc., Willem Hordjik, agreed with that assessment—to a point. He said that the younger machinists who work in his Bethlehem-based company’s stainless steel tube manufacturing operation are generally “less patient and creative in breakdown situations,” such as making changes to process routings and scheduling.

Hordjik added, however, that these same craftsmen “shine” when given the opportunity to find solutions as part of a team. “They’ve got to be involved,” he said. “You’d be surprised at how quickly they learn, particularly when it comes to technical issues.”

Another area where Xers tend to shine is the actual machining of parts. The effect of their proclivity for “extreme” sports on their work habits is debatable. Still, it seems logical that a person who belongs to a group that prefers freestyle snowboarding to golf and who grew up with computers and video games would bring a “go for it” attitude to the shop floor.

“I’ve never been afraid to run spindles hard right from the start,” said Basil Breininger, a 28-year-old programmer at a midsize CNC shop on the East Coast. “I figure I’ll never know what the machine can do until I’m on the edge with it.”

This isn’t just youthful bravado. A deeper look reveals that Breininger is a talented, highly trained individual who isn’t intimidated by the technology he relies on to earn a living.

Not everyone has Breininger’s “on the edge” attitude. It’s safe to say that older, conventionally trained machinists and programmers don’t universally agree with his philosophy. Traditional training tends to advocate a more conservative approach to machining parts.

Nor is Breininger’s way necessarily better than a more cautious one. It’s simply different, and managers must adapt accordingly to benefit from what Gen Xers bring to the party. Machine shops that leverage the work philosophies and skills of all their personnel will win out over those that don’t.

Trying to integrate all of these elements, however, can create some problems along the way. For example, CNC machines are the major cost/profit centers at most shops. A Gen Xer might be more proficient on this gear than a veteran machinist, but the vet, raised under the old rules of seniority, may feel that he has earned a shot at the controls. On the other hand, the young machinist—no matter how talented—is still inexperienced, and mistakes on CNC machines are typically very expensive.

It takes a savvy manager to smooth over these types of situations. And it takes an equally adept manager to reconcile Xers’ heightened desire for continuous challenge and rapid advancement with the need to minimize rework and equipment damage.

Breaking Traditions

Machine shop owners and supervisors may be wondering if the new batch of machinists and programmers has to be managed differently from their older counterparts.

Probably. Traditional management practices don’t always work with Gen Xers. They’re more self-sufficient and self-assured and, yes, at times, more self-ish. Managers who try to steamroll them with the autocratic tactics commonly used in small-to-medium-size shops dominated by one or two key individuals should prepare for an increase in turnover.

According to one shop supervisor, Gen Xers seek a workplace with a progressive approach to managing employees. “They don’t buy into the old divisions of labor and management,” he said. “They expect to have a say in their destiny.”

The CEO of Hamilton Tool Co. Inc. concurred. “We’re making more and more business decisions by committee,” said Martin Hamilton, whose Meadville, Pa., company produces cutting tools for the aircraft, ordnance and automotive industries. He added that “democracy in the workplace” is a relatively new idea to those in the manufacturing arena.

One toolroom manager said that, more than anything, members of Gen X respond to mentoring. “Our young hires appreciate it when they sense that someone is taking an interest in their career development.” His company’s floor supervisors make a point of getting “face time” with their youthful co-workers. The supers inquire about everything from the workers’ “comfort level” with their tools to the health of their families.

The toolroom manager added that, though it’s increasingly difficult in the brutally competitive manufacturing world, “people orientation”—showing concern for employees’ lives outside the shop—has resulted in a happier and more contented workforce.

Hamilton agreed, saying that it takes more than high wages and good benefits to keep the new wave of machinists happy. “My defined benefits plan—which, at times, has even included stock in the company—hasn’t seemed to make a difference [in retaining workers],” he reported.

Hamilton claimed, though, that the Gen Xers he employs seem energized by his substantial investments in CAD and CNC systems and, as a result, his operation is flourishing.

A number of conclusions about managing Xers can be drawn from the experiences of representatives at Hamilton Tool, Micro Tool and the other companies interviewed. Among them are that Generation X prefers leadership to formalized procedures, ongoing training in fast-growth technologies—like multi-axis CNC programming and electrical discharge machining—and compensation tied to performance, not longevity.

Clearly, younger machinists and programmers challenge traditional management practices. In meaningful and unprecedented ways, they are different from every generation that has preceded them.

Smart managers will recognize—and capitalize on—those differences.

About the Author

Mike Principato owns Synergetics Corp., an Easton, Pa., machine shop.

Gen Xers: Independent and Entrepreneurial

So who makes up Generation X? According to Rainmaker Thinking Inc., a research and consulting firm, Gen Xers are the 45 million individuals born in the United States between 1964 and 1977.

The New Haven, Conn., company describes the typical Gen Xer as creative, hard working, independent and entrepreneurial—characteristics that don’t fit the “slacker” stereotype that initially plagued Gen Xers.

According to Rainmaker, Gen Xers are more interested in developing marketable skills than in building a long-term relationship with an employer. They are interested in gaining knowledge and skills because they believe these tools will help guarantee lifelong employment.

Rainmaker’s research on members of Generation X reveals that:

- Sixty-seven percent describe their careers as “very important” elements of their lives, as opposed to only 54 percent of all adults.

- They are the most entrepreneurial group in the country. Eighty percent of Americans trying to start their own business are between the ages of 18 and 34.

- Sixty-six percent say that their biggest concerns are lack of job security and lack of economic opportunity.

- Only 30 percent say that they would go to their boss or employer for help or encouragement.

There are numerous theories about the forces that formed Generation X’s view of the workplace, which differs drastically from the views of earlier generations. Most researchers agree that many members of Gen X were disillusioned by the massive layoffs in the 1980s and early ‘90s.

Others argue that the onslaught of the computer age—with its well-known success stories, ample opportunities for quick learners and eye-popping salaries—turned young workers off to the “start-at-the-bottom-and-slowly-work-your-way-up” mentality.

Members of Generation X, according to Rainmaker, are demanding—and receiving—more in the workplace than their parents ever did. More flexibility, more responsibility and, in the long run, a more marketable set of skills.

—Lisa Mitoraj, Associate Editor

Related Glossary Terms

- centers

centers

Cone-shaped pins that support a workpiece by one or two ends during machining. The centers fit into holes drilled in the workpiece ends. Centers that turn with the workpiece are called “live” centers; those that do not are called “dead” centers.

- computer numerical control ( CNC)

computer numerical control ( CNC)

Microprocessor-based controller dedicated to a machine tool that permits the creation or modification of parts. Programmed numerical control activates the machine’s servos and spindle drives and controls the various machining operations. See DNC, direct numerical control; NC, numerical control.

- computer-aided design ( CAD)

computer-aided design ( CAD)

Product-design functions performed with the help of computers and special software.