It is October 1978. On Oct. 13, my discovery at the former Matra company in Frankfurt that PCD can be eroded by means of electric sparks was registered at the patents office. In October 2018, we looked back at 40 years of experience in the application of spark erosion for manufacturing and versatile application with polycrystalline blades of PCD- and PCBN-tipped tools.

But back to October 1978. Only a few days had passed since registering the patent. Forced to maintain silence, the team around the R&D staff member Dipl. Eng. Günter Hobohm, Gerhard Mai and Konrad Wagner had not yet been able to think a lot about applying this technology. Fortuity became our accomplice—with a telephone call.

A Mr. Denker of the company Resopal Werk H. Römmler GmbH in Großumstadt (today known as Resopal GmbH) answered. “Mr. Lach, I read that you presented milling tools at a trade show.” He was referring to productronica 1977 in Munich. I confirmed this and he continued: “We are having a problem. Can you build a profile milling cutter for us?”

Immediately I was wide awake. Only 14 days ago, I would have answered, “No, sorry.” But now? Most likely I answered with a drawn-out “yes” and requested more details.

Mr. Denker continued: “We call it an American milling cutter with profile for a post-forming work plate, with a cutting width of 45mm and a cutter diameter of 160mm.” (All checked and still shown in old documents at Lach Diamant.)

When the cutter dimensions were mentioned, my reply was “But, unfortunately, our production is not yet ready for this size.”

Denker replied: “It doesn’t matter. We are sending you two Leuco milling cutters with carbide blades and you simply take those off and solder on your diamonds.”

The conversation went that easy. However, it was so pivotal for the future of this cutting material, which was still in an early development phase, and for us as tool manufacturer and user, as well as for manufacturers of superabrasives, such as General Electric with its “compax” and “BZN” products and DeBeers with its “Syndite” product.

On the following morning, Günter Hobohm picked up the two carbide milling cutters. Now the carbide cutting edges were removed, cleaned, diamonds attached, cutting width was 45mm—oh gosh—there was a problem. The largest insert blanks at the time offered by GE only had a diameter of 13.2mm. We decided on a semicircle cut, so that a blade length of maximum 13.2mm was available. We had to add pieces. The inserts were only 13.2mm long and had to be soldered on in an overlapping way, tooth by tooth, to avoid creating scoring marks during the milling process.

Manufactured this way, the world’s first PCD cutting tool for machining wood materials (post-forming—coated as a kitchen cabinet plate) was manufactured as Z =4, but due to the necessary overlapping, this diamond milling cutter was really a Z-2 tool.

And Now, Only Profiling – Done!

Being an attentive reader, possibly an expert, you are right. At the time, this was not as easy as “soldering,” for example. Already the first diamond too, for milling on a double-end tenoner was a monoblock tool, resulting from the carbide tool bodies given to us, thus no cassette tool.

Again, another coincidence, or let’s rather call it a stroke of luck since the PCD cutting edge, starting with the very first milling cutter, was already prepared for the long tool life of the future compared to all other materials. Ultimately, profiling prepared PCD cutting edges was “child’s play” for us, because the company Matra did that on a FANUC wire EDM. For this reason, we are still very grateful to Mr. Schreiber and Mr. Becker.

After Lach Diamant agreed to manufacture diamond profile milling cutters for the first “wood customer,” we had to answer questions, dozens of times, on the part of Resopal during the development or manufacturing time from October 1978 to January 1979. “Yes, when can we start—customers demanding—or can you actually do this?”

Finally, on Jan. 5, 1979, we could report success. Günter Hobohm and I took the opportunity and personally delivered two firstlings to then watch the first use. I don’t necessarily want to say that we were shocked when we saw the big “monster” of a post-forming system—a double-end-tenoner. But we both were astonished. After mounting the cutter, the system started with a load roar and a few thoughts were going through our minds. “What happens now? Do the cutting edges hold up? Does the soldering hold up?” But all went well.

Before we went back home to Hanau, we asked “What do you think; how long will they be running?” We could have expected the answer “You are the specialists. A carbide milling cutter lasts approximately three to four hours, then it has to be resharpened. We work three shifts. Therefore, diamonds must hold up a bit longer, at least a week.”

We only nodded to that and said our goodbyes, promising to get back in touch with a week.

Top Secret

The discovery that PCD could be formed by spark erosion due to their electric conductivity was still treated as “top secret” by us. This information was kept even from GE, the PCD supplier. You never know!

Not to be misunderstood, the cooperation with GE (more and more with the headquarters in Worthington, Ohio) was increasingly positive, so that Lach Diamant could even influence the development of GE’s so-called compax during that time. For example, regarding the size development of the blanks, which had maximal widths of 3.8mm in the beginning, from manufacturing sizes of 6.4mm/8.1mm, leading up to available blanks with 13.2mm at the end of 1978.

From 1975 onward, PCDs were still scored with circular diamond saws at the carbide bottom by diamond manufacturers, depending on the segment/form that was being produced.

A week had passed by now, and we had not heard anything about our diamond milling cutter. In eager anticipation, we call Resopal, where a Mr. Essow had joined as contact person in the meantime, besides Mr. Denker. “No worries, all is well. Your diamonds are still running. There is still no end of the lifetime in sight.”

So, it is still running. This answer was repeated week after week. A certain nervousness began to set in. “They would not have taken this milling cutter and …” It is not known whether anyone at Resopal noticed our emerging suspicions, however, almost as a reaction, we were told in our next call that they would like another two diamond milling cutters with profile. The firstlings were still on the machine—for now over four weeks.

Conversation Between Father and Son

This was also the time when I asked my father, Jakob Lach, who was CEO like me, how we should further deal with this. I will never forget his answer: “I am now 85 years old. If you want to do this, you are welcome to go ahead and do it.” This really was the starting shot for foundation of the diamond company, “Lach-Spezial-Werkzeuge” as limited company on Feb. 13, 1979, in the notary’s office of my friend Gerhard Grossmann in Frankfurt.

Even in hindsight, it was a good recommendation of my father to split the Lach Diamant company, which was more oriented towards the metalworking industry, from the new company, with the aim of winning customers in the wood and plastics industry. Luck was a factor as well, since exactly at that time, the committee of industrial research associations (AIF = Arbeitsgemeinschaft Industrieller Forschungsvereinigungen) initiated company-specific supportive measures for helping start-ups of small and medium-sized businesses. The project “Diamonds machining wood and plastics,” started with the founding of Lach Spezial, could move ahead.

Employees were hired and machines, including a wire EDM, were ordered. R&D work could begin and, of course, acquisition of customers. Who needs Lach-Spezial tools for all wood materials? As is well known today, such a search falls under marketing. Today, one could say, “Look on the internet.” But in 1979? At least, even back then, we had supplier catalogs such as “Wer liefert was“ and company listings such as “ABC der Deutschen Wirtschaft“ and we already had trade shows that featured this material “wood,” such as “LIGNA,” a global trade show for wood machining, and the craft trade fair “Holz-Handwerk”.

In the meantime, approximately in March 1979, we knew that the diamonds profile cutters used for chipboards, coated on both sides, were still running at Resopal, much to our first customer’s delight, and no end of their lifetime was yet in sight.

Since January, the company Röhm in Darmstadt, had become another customer. We had successfully provided a milling cutter with two PCD edges as a “precutter” and one natural diamond blade as an “after-cutter” for polishing acrylic glass. For the Rowenta plant in Offenbach, we constructed a diamond profile milling cutter Z-4 under the new trademark “dreboform” for machining an abrasive plastic component. Only a few of the machining solutions were shown.

“The Cat was out of the Bag”

Apparently, a successful product but where to go with it? The small team of “Lach Specials,” my humble self, of course, included, was now already very euphoric. The key word was “wood”—the crafts trade show, so I thought as “wood layman” would be the place to find potential customers and inspirations. I stood in front of a very impressive compact and heavy machine, which gave me hope. It was one of the first numerically controlled routers by MAKA and used during the profile milling of a decorative plate made of medium-density fiberboard. I was able to enthuse the owner of this company, Mr. Lobedank, by listing possible lifetimes and surface quality during milling with diamond. We quickly agreed that he would show this “novelty” in action on his new router as a highlight at the upcoming LIGNA.

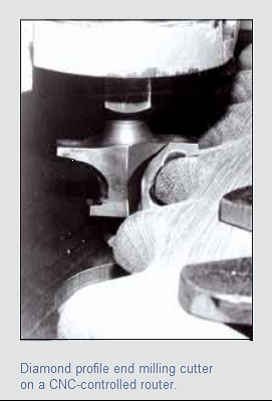

As so it happened. A dreboform PCD endmill, type FZ24/20, shaft 12mm, øx20mm, with plunge cut, was used. It machined veneered chipboard on a CNC router made by MAKA at 17,900 rpm. Performance tested in practice at 30,000 rpm. A maximum of 100 milling operations were achieved, with a comparable carbide tool. Also, a 300 times higher lifetime compared to carbide.

Yes, I can already predict that lifetimes of diamond tools for machining wood and plastics will play out at 250 to 300 times longer compared with the average possible performance of a carbide tool. There are many positive factors for this new technology and for the start-up company Lach-Spezial. It should finally be seen at the worldwide first presentation of diamond tools for machining wood and plastics at LIGNA 1979.

Our company surprised the industry experts with a tool program, complete with all until-then-known tools for the wood and plastic industry—as an alternative to carbide tools. The cat was out of the bag and the secret about the activities of Lach-Spezial was (almost) revealed. But this was only the beginning for the wood and plastic processing industry, furniture and parquet manufacturing industry, automobile and supplier industry, aircraft and wind power plant manufacturing machine and tool industry in general, and, in particular, for the companies Lach-Spezial and Lach Diamant. Visit vimeo.com/206233393 to watch a video about the companies.

P.S. By the way, the dreboform diamond profile milling cutters delivered to Resopal Werk H. Römmler GmbH on Jan. 5, 1979, came back for regrinding for the first time on June 1, 1979.

Related Glossary Terms

- abrasive

abrasive

Substance used for grinding, honing, lapping, superfinishing and polishing. Examples include garnet, emery, corundum, silicon carbide, cubic boron nitride and diamond in various grit sizes.

- computer numerical control ( CNC)

computer numerical control ( CNC)

Microprocessor-based controller dedicated to a machine tool that permits the creation or modification of parts. Programmed numerical control activates the machine’s servos and spindle drives and controls the various machining operations. See DNC, direct numerical control; NC, numerical control.

- electrical-discharge machining ( EDM)

electrical-discharge machining ( EDM)

Process that vaporizes conductive materials by controlled application of pulsed electrical current that flows between a workpiece and electrode (tool) in a dielectric fluid. Permits machining shapes to tight accuracies without the internal stresses conventional machining often generates. Useful in diemaking.

- endmill

endmill

Milling cutter held by its shank that cuts on its periphery and, if so configured, on its free end. Takes a variety of shapes (single- and double-end, roughing, ballnose and cup-end) and sizes (stub, medium, long and extra-long). Also comes with differing numbers of flutes.

- gang cutting ( milling)

gang cutting ( milling)

Machining with several cutters mounted on a single arbor, generally for simultaneous cutting.

- metalworking

metalworking

Any manufacturing process in which metal is processed or machined such that the workpiece is given a new shape. Broadly defined, the term includes processes such as design and layout, heat-treating, material handling and inspection.

- milling

milling

Machining operation in which metal or other material is removed by applying power to a rotating cutter. In vertical milling, the cutting tool is mounted vertically on the spindle. In horizontal milling, the cutting tool is mounted horizontally, either directly on the spindle or on an arbor. Horizontal milling is further broken down into conventional milling, where the cutter rotates opposite the direction of feed, or “up” into the workpiece; and climb milling, where the cutter rotates in the direction of feed, or “down” into the workpiece. Milling operations include plane or surface milling, endmilling, facemilling, angle milling, form milling and profiling.

- milling cutter

milling cutter

Loosely, any milling tool. Horizontal cutters take the form of plain milling cutters, plain spiral-tooth cutters, helical cutters, side-milling cutters, staggered-tooth side-milling cutters, facemilling cutters, angular cutters, double-angle cutters, convex and concave form-milling cutters, straddle-sprocket cutters, spur-gear cutters, corner-rounding cutters and slitting saws. Vertical cutters use shank-mounted cutting tools, including endmills, T-slot cutters, Woodruff keyseat cutters and dovetail cutters; these may also be used on horizontal mills. See milling.

- polishing

polishing

Abrasive process that improves surface finish and blends contours. Abrasive particles attached to a flexible backing abrade the workpiece.

- polycrystalline diamond ( PCD)

polycrystalline diamond ( PCD)

Cutting tool material consisting of natural or synthetic diamond crystals bonded together under high pressure at elevated temperatures. PCD is available as a tip brazed to a carbide insert carrier. Used for machining nonferrous alloys and nonmetallic materials at high cutting speeds.

- profiling

profiling

Machining vertical edges of workpieces having irregular contours; normally performed with an endmill in a vertical spindle on a milling machine or with a profiler, following a pattern. See mill, milling machine.

- sawing machine ( saw)

sawing machine ( saw)

Machine designed to use a serrated-tooth blade to cut metal or other material. Comes in a wide variety of styles but takes one of four basic forms: hacksaw (a simple, rugged machine that uses a reciprocating motion to part metal or other material); cold or circular saw (powers a circular blade that cuts structural materials); bandsaw (runs an endless band; the two basic types are cutoff and contour band machines, which cut intricate contours and shapes); and abrasive cutoff saw (similar in appearance to the cold saw, but uses an abrasive disc that rotates at high speeds rather than a blade with serrated teeth).

- wire EDM

wire EDM

Process similar to ram electrical-discharge machining except a small-diameter copper or brass wire is used as a traveling electrode. Usually used in conjunction with a CNC and only works when a part is to be cut completely through. A common analogy is wire electrical-discharge machining is like an ultraprecise, electrical, contour-sawing operation.