Bird’s eye view

Bird’s eye view

If you're not monitoring the condition of your CNC equipment, you're machining in the dark.

If you're not monitoring the condition of your CNC equipment, you're machining in the dark.

What's your production efficiency? Do you know how many hours your spindles turned last month or the last time your operator made an offset? Is the darned machine even turned on? If you don't have some form of machine monitoring in place, even a manual one, you don't have a clue.

Monitoring systems keep an eye on most any CNC machine tool, from that tired-looking horizontal lathe to the brand-spanking-new 5-axis horizontal machining center that just hit the loading dock. And depending on the vintage of the machine control, you can know everything from the cause of that loud crash you just heard to why the operator has been standing in inspection for the past half hour.

Despite these benefits, many shops would rather avoid the technical headache of putting their machine controllers "on the net," preferring instead to learn what's going on in the shop through the information entered on employee time cards or the often-questionable data collected from shop floor data collection systems.

No Red Light

In the case of basic monitoring, the only thing to fear is fear itself. According to Timothy Zott, president of Remote Machining LLC, Southfield, Mich., implementing a basic monitoring system is simple and affordable, with hardware starting at around $1,000.

Zott can teach an old light stack new tricks. By interfacing directly to the machine's "Christmas tree," his firm's Remote Light Stack device converts the signals from those red, yellow and green lights into easy-to-understand text messages, e-mails or status displays on a Web page. "It gives you a power of notification that you didn't have before," Zott said.

Equipment diversity is one of the biggest obstacles small shops face when trying to set up monitoring systems. "Walk into most shops and you'll see a mixed bag of machines," Zott said. "One Makino, one YCM, maybe a couple of Mazaks. Each of those OEMs offers a monitoring solution, but it only works for that builder's machines. You're not going to go out and spend a few thousand bucks for each of the different monitoring systems required on all of those machines."

The Remote Light Stack is ecumenical. It doesn't care whose machine it's plugged into. And placed in the right hands, it can do more than call you in the middle of the night when a machine runs out of stock. "For example, we have one shop that set up a laser measuring system in the machine for tool measurement," Zott said. "When cutting tool wear comes within a certain range, it kicks off a warning, which triggers the yellow light. This in turn sends a notification that the machine needs attention."

To actually do something about that yellow light without having to get out of bed, however, requires something more. That's where the company's Remote Monitoring device comes in. It allows a user to see the machine control as if he is standing in front of it. "It's like ripping away the face of the control panel and taking it home," Zott said. "As long as you don't need to touch any of the machine's electromechanical switches, you can fix whatever needs fixing directly from the Remote Monitoring device."

Courtesy of RYM

Information from RYM's FactoryWiz monitoring system can be sent to shop displays, such as this one.

But the problem with any remote monitoring solution is that you can't just plug it in and go home. "The machine has to be set up for a lights-out situation," said Matt Jamison, vice president of Jamison Industries Inc., Taylor, Mich., a small-part job shop. "People say they want remote monitoring, but they're going to be up all night if they don't first maximize the amount of time they can run unattended."

That means purchasing machine accessories, such as high-pressure coolant systems, part conveyors and, especially, broken-tool detectors. "Break one tool and you can pile up the whole turret," Jamison said. "But with tool detection, the machine alarms out and stops if there's a problem."

Prior to installing the Remote Light Stack on his Citizen lathes, Jamison would fill the machine's autoloader with stock and go home. The next morning, he'd come in expecting 600 parts in the basket and might find only two. Those days of unpredictability are gone. "Now I get a text message when the machine stops," he said. "For example, I was on my way home last week, not 2 miles from the shop, when I received an alert. I turned around, fixed a simple problem and was home in time for supper. Even if I'm in the office, working on CAD drawings or doing paperwork, the Remote Light Stack frees me up to do other things."

According to Jamison, people who put cameras on their machines still have to watch a monitor, and a camera doesn't indicate when a problem happened. "This solution tells me within seconds," he said. "Now when I quote X number of parts each month, I know I can count on the unattended portion of my available shop hours."

Bob vs. Jim

Larger operations may have different monitoring needs, such as interfacing with business management software, according to Michael P. Rogers, director of automation and OEM relations at Predator Software Inc., Beaverton, Ore. The company offers a suite of factory automation products, including tools for data collection, machine networking, reporting, machine simulation and document management.

Courtesy of RYM

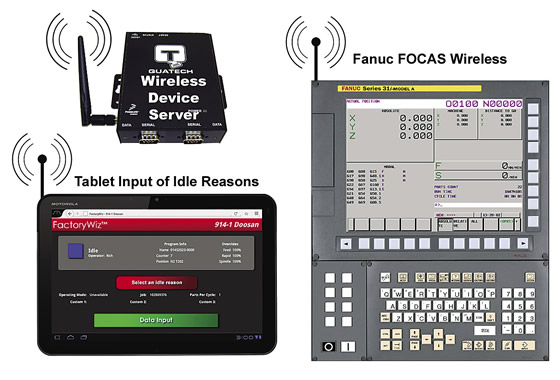

There are several ways process monitoring systems can be set up, including wired and wireless systems. This diagram is of a wireless system that interfaces with a Fanuc Focas control.

"One of our goals is to give the shop owner a view of what's happening on the floor, so he or she can see trends and fix them before they become problems," Rogers said. "You shouldn't have to wait for a report that says you lost your butt last month." To avoid that situation, Predator works closely with enterprise resource planning and manufacturing execution systems software developers to interface machine and production information directly to business management systems, giving managers better access to real-time information.

Predator also works with machine tool builders and control manufacturers. "The problem we have today is that everyone's products have become more sophisticated and provide a very rich feature set," Rogers said. "But there are relatively few customers that can understand, let alone take advantage of, all the technology that's pouring into these products. We provide tools that help solve that situation."

One of those situations was described previously by Remote Machining's Zott, where shops end up with a Heinz 57 mixture of machine brands and control systems. "If they were all hooked together, you could achieve a complete lights-out manufacturing facility, but the sad truth is that most builders know everything about their own products and nothing about anyone else's," Rogers said.

The goal of third-party software developers, such as Predator, is to be a conduit to all brands of equipment, collecting data from anything on the shop floor and sending that information to a central database. "So if you want to know Bob's performance compared to Jim's, you can write a report that shows how they did by date, cell and part number," Rogers said. "You can then start asking the right questions: What is wrong out on the shop floor, and how can I fix it?"

That information isn't free, of course, and it takes time to implement and learn a new system. Rogers noted equipping a small production cell with all the software's bells and whistles might cost $30,000 to $40,000. However, payback is "pretty darn quick," he said. As an example of where this technology can take you, Rogers pointed to a machine shop in Michigan that makes spool valves for the aerospace industry. By equipping a robotic EDM cell with Predator automation software, it runs lights-out during the weekend. Predator manages everything from load/unload of the machines and wash stations to notifying the appropriate personnel if there's a problem. "They load it up with 300 parts on Friday afternoon and come in Monday to find clean, shippable product," Rogers said. "All they have to do is bag 'em and ship 'em."

Remote Service

As previously mentioned, most machine builders offer their own monitoring systems. Okuma America Inc., Charlotte, N.C., has been making long-distance calls to machine tools for as long as its THINC control has existed. Brian Sides, Okuma's director of technology, said, "Just like any other remote desktop application, we can look at settings, alarms and service history and possibly save the cost of an on-site service call."

That's great when the red light is flashing and you don't know why, but in terms of remote production management, Okuma generally leaves that to someone else. Sides said: "Our strategy is to look for 'best of the best'-type partners for our automation. The THINC control is open enough that anyone can go in and use the data for remote monitoring. We want to make it easy for them to do that."

Courtesy of Okuma

Okuma's THINC control connects via Ethernet to the corporate network, enabling machine monitoring from the office.

Activity is high in this area. Within the past 12 months, Sides has fielded an increasing volume of calls from shops asking about remote monitoring and looking for machine options to support it. Whether it's how to install a simple monitoring device or integrating a cell controller that does autonomous work scheduling, Sides noted people want to know what's going on with their machine tools. "When the doors are open on a machine, you already know something is preventing that machine from cutting metal," he said. "Now you need to know why."

Despite the newfound interest, Sides explained that none of this has happened to the degree that it should. "Many shops are still behind the eight ball on this," he said. "Some of the reshoring that we've seen lately is simply because it's challenging to make complex parts in less technically capable countries. As a result, there's a need to do things locally. That helps drive shops to focus on productivity gains and better efficiencies to compete with overseas markets as well as one another. Lights-out machining and the remote monitoring that accompanies it are big factors in manufacturing success." More shops need to implement this kind of technology, he added.

However, just because the green light is on doesn't mean the machine is making good parts. Remote machining often involves measuring parts and making the appropriate adjustments to keep them in tolerance. "By integrating probing or laser measurement systems, you can extract the relevant data, look at your machines remotely and know what's going on qualitywise," Sides said.

Straight Talk

Back in the early 1980s, when people still struggled with tangled wads of paper tape and wondered what all those little holes signified, John Hosmon had the vision of replacing tape readers. His company, Refresh Your Memory Inc., San Jose, Calif., was founded on this premise. Flash forward 20 years to the birth of remote monitoring. "Every communication package was adding a monitoring function, but nobody in the industry had anything that was very usable," Hosmon said.

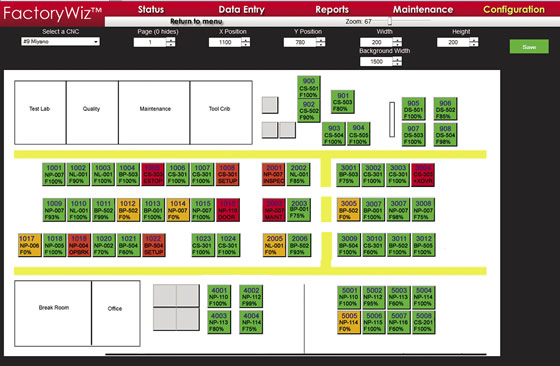

That changed when Hosmon was convinced by one of his field engineers to target a glaring hole in the market. "There were lots of options out there, but the choice was between complicated and expensive," he said. "We wanted to introduce a solution that was neither of those things." The result was FactoryWiz, a monitoring and data collection package that, according to Hosmon, can talk to most any device and make it accessible almost anywhere.

"I don't think any shop should consider a solution that is only accessible through a desktop PC," says RYM's Vice President of Engineering Richard Hefner. "Users should expect those features to be just as accessible from their cell phone, tablet computer or anything else with a Web browser. And all of that needs to be customizable."

Courtesy of RYM

An ADAM unit from RYM interfaces to machine relays on a Makino machining center.

Like most monitoring systems, Factory- Wiz uses a hardware device known as a data acquisition module to tap into the electrical signals of light stacks on older machines. "On more modern controllers, far more information is available," Hosmon said, adding that FactoryWiz supports FANUC Focas, Siemens 840, Mazak Matrix, Okuma THINC, Haas MNet and many others. "That information can include current cycle times, alarm information, offset changes and override-dial positions.

"The more native protocols we support without the need for intermediate hardware or software adapters, the more we can give end users for their dollar," Hosman continued. "We even support MTConnectâif you can find it on a machine."

Hosmon sits outside the cheering section for MTConnect, the metalworking industry's protocol for connecting machine tools and other equipment. "If you've been in the business long enough, you know it can be a challenge to get the machinery guys to play nice together."

Can't We All Just Get Along?

One person who does cheer is TechSolve Inc. Senior Project Engineer Ron Pieper. TechSolve, a process improvement provider founded in part by the city of Cincinnati to help foster efficiency in Ohio's manufacturing companies, is an active sponsor of the MTConnect Institute, whose stated goal is the creation of a communications standard that allows seamless data sharing between disparate manufacturing systems.

Okuma's Sides is likewise a big fan. "MTConnect is driving much of the recent uptick in remote monitoring," he said. "People find it easier to connect their machines using one standard interface, and Okuma stands firmly behind the MTConnect initiative."

Pieper supports that statement with an analogy. "If I travel to Europe or China and I want to plug in my laptop, I'm going to need an adapter. With MTConnect, I can easily plug in wherever I go."

Without MTConnect, it's still possible to hardwire that laptop or build a custom adapter, but that's inherently less efficient. "In yesterday's world, Okuma spoke Okuma, Mazak spoke Mazak and Makino spoke FANUC with a slight accent," Pieper said. "Now that each of those builders has standardized their interfaces through MTConnect, they all speak the same language."

How does that help you know your machine just crashed? If you have an MTConnect-enabled machine and a remote monitoring software package, all you have to do is plug the machine into your network, tell the server where to find it and start collecting data. To that end, TechSolve developed ShopViz. "We saw an opportunity to take advantage of the MTConnect protocol, starting with small to medium-sized manufacturers," Pieper said. "We wanted to give them a monitoring system that would be within their price range and, more importantly, is digestible to them."

To avoid the stomachache of expensive servers and the IT geeks who take care of them, TechSolve developed a lightweight "eavesdropper" that collects data from machine tools and transmits it to an Amazon-hosted cloud-computing server accessing the information.

"All you're doing is using these small programs to gather data and shoot it out of the building," Pieper said. "The result is visibility from any Internet-capable device into what your machines are doing right now."

The Three A's

Pieper explained that there are three actions shops can take, and they all start with the letter A. Number one, be active, even if it means collecting data manually, typing it into a spreadsheet to analyze it or using pencil and paper. "Maybe it takes some time, but darn it, at least you're doing something good," he said.

Courtesy of RYM

RYM's FactoryWiz enables users to see the status of every machine on the shop floor.

Or be aggressive. "Invest in a full-blown automated monitoring system so you're getting actual data that isn't washed by people's opinions. You can avoid the time spent having a human collect the data manually, and have more time to analyze what's going on in the shop, and make decisions based on that."

The last option is being apathetic. "Do nothing," Pieper said. "Maybe you think you're making plenty of money right now, but this is a cyclical industry: It will hit the floor at some point. If you don't want to see the auctioneers at the door, you ought to do something now to better your company."

Whichever "A" best describes your shop, according to Pieper, one is most important: American manufacturing. "If we want to keep the jobs here, we have to get better," he said. "It's that simple. Machine monitoring is the quickest, easiest and most effective way for all of us to improve together."

So what are you waiting for? Stop reading and get monitoring. CTE

About the Author: Kip Hanson is a contributing editor for CTE. Contact him at (520) 548-7328 or [email protected].

Contributors

Jamison Industries Inc.

(734) 946-3088

www.jamisonind.com

Okuma America

(704) 588-7000

www.okuma.com

Predator Software Inc.

(503) 292-7151

www.predator-software.com

Refresh Your Memory Inc.

(866) 796-4362

www.rym.com

Remote Machining

(888) 326-5057

www.remotemachining.com

TechSolve Inc.

(800) 345-4482

www.techsolve.org