Hot diamonds and barber pole

Hot diamonds and barber pole

The Grinding Doc addresses the cause of barber pole lines in workpieces.

Dear Doc: I cylindrical-traverse-grind rolls and am getting spiral marks on the workpiece. I checked the alignment of the wheel/workpiece axes, and they seem OK. Could there be another reason for the marks?

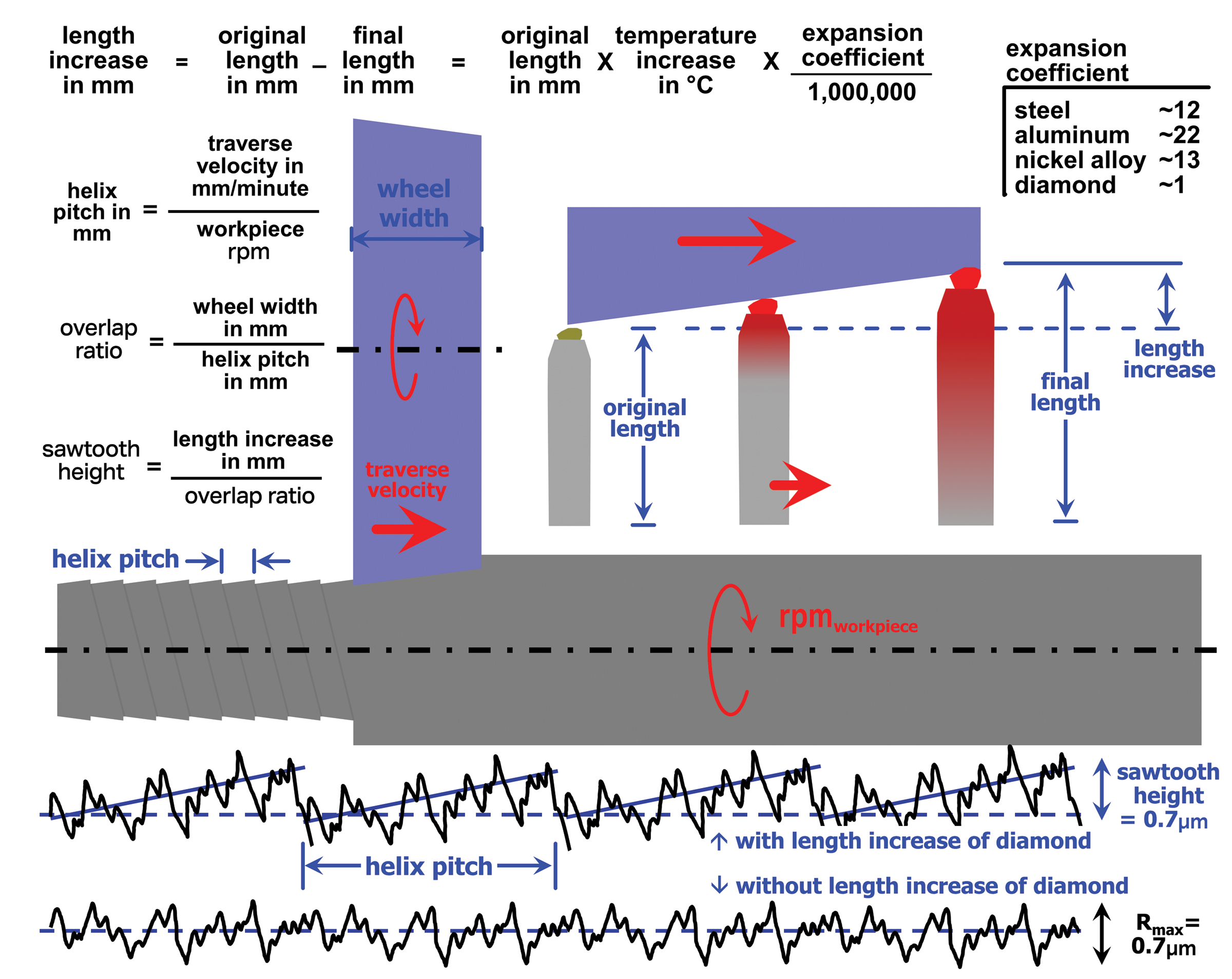

The Doc Replies: First, let's clarify spiral marks. What people refer to as spiral marks can be caused by dressing too fast, intermittent contact between the dresser and wheel or self-excited chatter with a phase shift, just to name a few reasons. When cylindrical traverse grinding, the most common type of spiral marks is what I call barber pole helix lines. Here, a single helix circles the workpiece, with a fixed pitch (see figure). In addition to misalignment between the wheel and workpiece, another cause of barber pole lines is temperature-induced diamond tool growth as the diamond traverses the wheel.

Dressing generates heat, some of which goes into the dresser. Let's say that from the beginning to the end of the dress, the overall bulk temperature of a 25mm-long, single-point, steel shaft dressing tool increases 10° C. During dressing, the tool shaft will increase in length by 3µm. The equation is 25 × 10 × 12 ÷ 1,000,000 = 0.003mm, where 0.000012, or 12 × 10-6, is the material's expansion coefficient. That may not seem like much, but it might be enough to cause visible barber pole marks on a workpiece, especially because that sharp corner on the wheel digs into the workpiece.

In addition, if we consider that a half-carat, single-point diamond has a diameter of around 4mm and that diamond heats up 100° C during dressing, that's 4 × 100 × 1 ÷ 1,000,000 = 0.0004mm = 0.4µm, and we have to add that to the length increase.

The solution is to keep a high-pressure stream of coolant on the diamond during dressing. You also can dress the sharp edge from the wheel. This approach is cheating because it doesn't address the root cause, but it does work pretty well.

The equation for thermal expansion can be used in lots of applications. What happens to a 300mm-dia., aluminum-hub wheel if it heats up by 5° C? It'll grow about 0.033mm (300 × 5 × 22 ÷ 1,000,000). And perhaps it will make holding size more difficult. What happens to a 50mm-dia., nickel alloy workpiece when it heats up during grinding by 15° C? It'll grow about 0.010mm (50 × 15 × 13 ÷ 1,000,000). Then, after grinding and cooling to room temperature, the workpiece will be undersized by about 0.010mm. What if the 200mm-high steel column where a spindle on a machine is mounted heats up during the day by 5° C? The size variation will be 0.012mm (200 × 5 × 12 ÷ 1,000,000).

You get the idea. Keep in mind that this formula isn't exact. Geometry has an effect, and the thermal expansion coefficient varies for different grades of steel and even with temperature itself. But the formula will put you in the ballpark to see the effect of temperature.