Doing it the Hard Way

Doing it the Hard Way

Thinking about taking the leap into milling hardened steels? Why would you? After all, if your shop has been successfully grinding, jig boring and EDMing hardened materials, why change?

Requirements for milling hardened steels.

Thinking about taking the leap into milling hardened steels? Why would you? After all, if your shop has been successfully grinding, jig boring and EDMing hardened materials, why change?

For starters, hard milling might be more profitable. Michael Minton, national application engineering manager for Methods Machine Tool Inc., Sudbury, Mass., explained that hard milling not only eliminates costly finishing operations, but produces a higher quality part than does traditional machining methods.

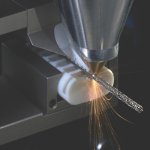

Courtesy of Greenleaf

Roughing hardened tool steel with a facemill tooled with ceramic inserts.

"By machining after heat treatment, you not only avoid secondary operations, but also eliminate problems with workpieces being twisted, bent or otherwise out of shape due to heat treating," Minton said. "This allows you to make a part with higher accuracy and better dimensional characteristics compared to parts heat-treated after machining."

In general, hard milling involves cutting primarily tool steel or precipitation hardening stainless steel, such as 15-5 or 17-4, that has been hardened to at least 50 HRC. After a workpiece is roughed in the soft state, it is sent to the furnace for hardening and then finish machined with coated carbide, ceramic or PCBN tools. The amount of metal removal in the hardened state is minimal—perhaps just 0.010 " to 0.020 " per surface—making this process feasible for most hardened parts.

Depending on the workpiece configuration, production volume and amount of stock removal, however, it may be feasible to machine the workpiece entirely from a hardened state. Modern machine tools, advanced tool steels and high-speed steels…" title="Cutting tool materials include cemented carbides, ceramics, cermets, polycrystalline diamond, polycrystalline cubic boron nitride, some grades of tool steels and high-speed steels…" aria-label="Glossary: cutting tool materials">cutting tool materials and sophisticated CAM programs make what was once a highly improbable machining operation into one within the reach of many shops. According to Minton, the advantage of machining from a hardened state is having to cut it only once.

Good Machines

However, you're not going to accomplish this on an old knee mill. "As always, machine tool construction plays a large part in the level of success you'll achieve with hard milling," Minton said. "You can be successful with linear way machines, provided they are made well."

Another key is spindle design and construction. "That's the only thing holding the tool and keeping it stable, so very solid, HSK-capable spindles typically are required," he added.

Minton noted that volumetric accuracy is also important. What does accuracy of the machine tool have to do with cutter life? "Because of the need for consistent chip loads and predictable stock removal, the more square the spindle is to your workpiece, the better your tool life."

Danny Haight, national milling product manager for Mitsubishi machine supplier MC Machinery Systems Inc., Woodale, Ill., agreed. "You need a solid machine tool, one with bridge construction and a rigid spindle. You also need hand-scraped machine surfaces because they are more accurate and better at dampening vibration than conventionally ground surfaces."

Of course, the level of machine rigidity depends on what type of hard milling you're doing. "There's a big difference between the cutting forces generated when finish machining a mold for a hearing aid vs. roughing a mold cavity for a telephone or an automobile turn signal lens," Haight said. "Bigger DOCs mean higher cutting forces, which in turn require a more rigid machine tool."

Haight explained that because of the demanding toolpaths required for typical hard milling jobs—3-D contouring consisting of many short, high-speed movements designed to deliver consistent cutter engagement—the machine controller is also very important.

He said: "The control should have good look-ahead capabilities and fast calculation times. The machine should be very responsive when changing directions or going in and out of corners. You need to maintain a constant chip load if you want your cutters to last."

Tough Tools

When milling materials from 50 to 60 HRC, not just any cutter will do. Not only is the workpiece very hard, but to reduce thermal fluctuations on the cutting tool, machining is typically done dry. For this, you need tough tools.

One company offering such tools is SGS Tool Co., Munroe Falls, Ohio. Product Manager Jason Wells said SGS' Z-Carb MD solid-carbide endmills are designed for hard milling, including a negative rake to strengthen and support the cutting edge, an AlTiN coating for heat resistance and an eccentric relief with a radial grind to also strengthen the cutting edge.

Courtesy of Makino Inc.

Hard milling miniature mold cavities.

"Due to the high level of energy needed to create a chip in hardened steels and the abrasive action of the workpiece, you need a tool with a lower-volume cobalt and fine-grain substrate to endure the high loads and temperatures seen in dry machining," he added.

Coated carbides offer a good trade-off between heat and wear resistance and between strength and toughness, according to Wells. "It's all about compromise. Ceramics and PCBN definitely have good heat and wear properties, but are more fragile when it comes to shock and imperfect cutting conditions."

Applications Engineer Dale Hill of Greenleaf Corp., Saegertown, Pa., concurred. "Ceramics don't do well in situations where you have vibration, excessive tool overhang and less-than-rigid spindles or fixtures. Failures in ceramics are generally mechanical in nature." Even under normal milling conditions, the ceramic tool flexes as it enters and exits the cut. "It's unavoidable," he said. "This flex causes chipping of the cutting edge at a microscopic level. What appears as flank wear is actually microchipping caused by deflection and forces on the tool; as the microchips propagate, the tool eventually fails."

Despite this, however, ceramics are widely applied for milling hardened steels, irons and superalloys. That's because carbide's cobalt binder begins to soften at around 1,600º F, while ceramics can operate effectively at temperatures up to about 4,000º F. "Ceramic comes in where carbide leaves off," Hill said, explaining that the higher the hardness, the more heat generated during machining.

Courtesy of SGS Tool

Three-dimensional contouring of hardened steel using a ballnose endmill.

Because of this, ceramics can successfully machine into HRCs in the mid-60s. "We've even pushed into the high 60s," Hill said. "Because ceramic is indifferent to heat, cutting speeds can be much higher. In many cases, carbide's toughness allows a higher chip load per tooth, but the significant speed increase offered by ceramic offsets that higher feed rate. In most cases, ceramic tools will produce much higher metal-removal rates."

It comes down to economics because a high-quality carbide insert might cost $7 to $8 compared to $20 for a ceramic one. And when the insert costs nearly three times as much, you have to ask if it can remove at least three times as much metal. "The answer is generally yes, but you've got to weigh all the machining factors," Hill said. These include insert life, the cost of the inserts, time to change out a worn set of inserts, required part accuracy and machine capabilities. "It's all about total metal removal."

Geometries at Work

As with carbide, toolmakers change the geometry of a ceramic tool for cutting hardened materials. Hill is a strong believer in positive geometry tools for softer materials, where built-up edge can be an issue. "Chip flow is critical when you're under 45 HRC. But as the hardness goes up, we go to negative tools. We don't have BUE problems with hard machining."

Courtesy of Surfware

Constant cutter engagement is critical in hard milling operations.

When hard milling, it's important to avoid shocking the tool, especially a ceramic one. This can be accomplished by reducing the feed rate on entry and exit, taking a circular toolpath into the workpiece and ramping into pockets and cavities. CAM systems do this automatically, according to Hill.

As proof, he related a story about a WESTEC show where he'd been struggling with tool life during a hard milling demo. "One of the CAM guys came over from a neighboring booth and offered to reprogram our toolpaths," Hill said. "When he was done, tool life went from 15 to 20 minutes all the way up to an hour."

Hill attributed this success to better control of tool engagement and adjusting for chip thinning. "You need to maintain a constant average chip thickness, and chip thinning can occur if the radial and axial cutter engagement of the cutter decreases," he said. "As the chips get thinner, you need to increase the feed rate to compensate. Otherwise, you'll end up rubbing the cutter to death."

When cutting steels harder than 65 HRC, coated carbides are used with limited success. Ceramics do a decent job if the DOCs are decreased appropriately. But, according to Gabriel Dontu, global superhard technical leader for Kennametal Inc., Latrobe, Pa., PCBN easily cuts hardened steels up to 68 HRC and can cut materials as hard as 78 HRB. PCBN is twice as hard as any ceramic or carbide material. The trade-off is toughness—the harder the cutter, the less tough it is. This limits the application of PCBN, especially on interrupted cuts.

"PCBN is a composite material, made of cubic boron nitride particles mixed with a binder," Dontu said. "It is created under volcanic-type temperatures and pressures—imagine a three-story tall press pushing on a tube the size of a tennis ball." About 90 percent of commercial PCBN is made into disk-shaped wafers, up to 100mm in diameter and 3.2mm thick, which are then sliced into segments and brazed onto a carbide substrate.

Courtesy of Greenleaf

Indexable ceramic cutters suitable for hard milling.

This complex process limits the geometries of PCBN tools to relatively simple shapes while also making them costly. PCBN can cost 10 times as much as comparable ceramics and carbides. However, PCBN tool life is up to five times higher, according to Dontu.

How is 10 times the cost but only five times the life justifiable? "PCBN allows you to hold very tight tolerances with minimal wear," Dontu said. "This means that, for example, on large molds you can machine the entire cavity with a single PCBN tool and avoid having to blend in the middle of a cut after a tool change."

Like ceramics, PCBN tools are presented at a negative angle to the workpiece. Edge prep is paramount with PCBN, and a K-land or T-land is ground on the tool, depending on the operation. Unfortunately, PCBN tools also suffer some of the same failure modes as ceramics. They work best under rigid, predictable cutting conditions, and lack toughness compared to carbide. For this reason, they are typically used only for finishing, and are reserved for the most demanding applications, such as extremely hard machining, tight-tolerance requirements and long production runs.

Taking the Right Path

As with other machining operations, even the best cutting tool will fail when hard milling if it's not programmed correctly. Unlike CAM programming for softer materials, where cutting parameters are typically broad and more forgiving, machining hardened workpieces requires predictable and consistent toolpaths. One company specializing in toolpath generation for hard milling is Surfware Inc., Camarillo, Calif.

"Precisely controlling the engagement angle of the cutter throughout the toolpath is the key to increasing tool life, because the engagement angle determines how long the tool tip is in contact with the material," said Alan Diehl, CEO of Surfware. "The greater the angle, the longer the tool is engaged and the greater the amount of heat inflicted on the tool."

According to Diehl, Surfware's Surfcam controls the engagement angle automatically, thus reducing tool temperature while increasing tool life and the mrr. This becomes even more important when machining hardened materials where, as engagement increases, cutting-edge temperatures increase exponentially.

Delcam Inc., Salt Lake City, is another software developer promising better toolpaths for hard milling. Mark Cadogan, vice president of sales for Delcam, said, "We use a patented point-distribution technology that reduces sharp angle changes while still providing constant cutter loads." The technology allows the programmer to input and automatically distribute as many points as desired, and the software will then drive the cutter through those points in the most accurate way possible, according to Cadogan. "This is great for machines that can handle high amounts of data, and works especially well for detailed 3-D surfaces in hardened steels."

Although it's probably best to hang onto that grinder, jig borer or EDM your shop uses for cutting hardened steels just in case, milling those materials instead can provide numerous benefits when the process is understood and proper tools, equipment and software are in place. CTE

Although it's probably best to hang onto that grinder, jig borer or EDM your shop uses for cutting hardened steels just in case, milling those materials instead can provide numerous benefits when the process is understood and proper tools, equipment and software are in place. CTE

About the Author: Kip Hanson is a manufacturing consultant and freelance writer. Contact him by phone at (520) 548-7328 or e-mail at [email protected].

Hard milling: Bringing it all back home

Hard Milling Solutions Inc., Romeo, Mich., regularly hard mills plastic injection molds, tooling for the can industry, forging dies and other workpieces that can exceed 60 HRC. "We cut as hard as anybody out there," said owner Corey Greenwald. The shop not only cuts hard, but competitively, and is seeing jobs once lost to China returning.

The process varies depending on the workpiece. "We make some 5 "×5 " forging dies out of 50-HRC H-13 tool steel. We purchase the raw blanks, send them out for heat treatment, then rough and finish mill, drill and thread mill the holes, all from the hardened state."

Deciding whether to rough in the hardened state or not depends primarily on the volume of material removed. "If I have a workpiece where I'm removing more than 30 percent of the blank, I'll usually rough it soft, heat-treat and then finish machine in the hardened state," Greenwald said. This is especially true on anything above 55 HRC. "It's almost like trying to cut carbide with carbide. You want to bring it as close to the finished size as possible beforehand to avoid that problem."

Hard Milling Solutions primarily applies coated carbides, as well as some PCBN tools for finishing work, especially on more abrasive workpiece materials such as hardened tool steels. The shop routinely holds tolerances as tight as +0.0002 "/ -0.0000 ". "We're doing work that previously would have been done on a jig grinder."

Sound tough? It gets tougher. Most of a typical job is performed unattended. "Walk out to our shop floor and you'll see there's nobody standing in front of the machines. We were one of the first in the country to do this, and when we started out, the knowledge wasn't available," Greenwald said. "The key is not just the hard milling—it's the data. You need to collect the data and save it to a database, so you can cut lights out even on hardened materials."

The shop has 46 " Samsung TVs on the wall showing live video from inside the machines. "We run one shift. At night, the machine can text message the operator at home if there's a problem, and he can then remotely access the machine, take control, go to the alarm screen, correct the program and change tools.

"It's not rocket science, but it's a lot closer to it now than it used to be," Greenwald continued. "As the part materials get harder, all the forgiveness goes away. You have to do everything right—toolpaths, cutters and equipment. You make a mistake, and you're going to smoke your cutter the instant it hits the part. Worse, you might burn up a $30,000 spindle."

In addition to the machine, peripherals such as lasers, probes and software are also critical to hard milling. With this technology and highly skilled machinists, Greenwald finds that many jobs previously sent overseas are coming back.

"We're competitive with China," he said. "What used to take 20 hours of manual labor can now be done in a little over an hour. It's not about throwing a bunch of people at it anymore."

—K. Hanson

Contributors

Delcam Inc.

(877) DELCAM

www.delcam.com

Greenleaf Corp.

(800) 458-1850

www.greenleafcorporation.com

Hard Milling Solutions Inc.

(586) 336-9737

www.hardmillingsolutions.com

Kennametal Inc.

(800) 446-7738

www.kennametal.com

MC Machinery Systems Inc.

(630) 860-4210

www.mcmachinery.com

Methods Machine Tools Inc.

(877) 668-4262

www.methodsmachine.com

SGS Tool Co.

(330) 688-6667

www.sgstool.com

Surfware Inc.

(818) 991-1960

www.surfware.com