Dry Run

Dry Run

Dry milling and turning grow in popularity day by day, but dry drilling is nanother matter. Because of the nature of drilling, it's more difficult to nperform this operation without coolant. Still, progress is being made, nthanks to research and more sophisticated coatings.n

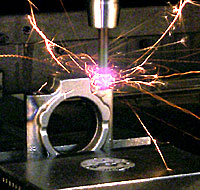

Dry drilling in cast iron with a Guhring solid-carbide RT 100 with FIREX and MOVIC coatings.

At trade shows and on shop floors, there's a lot of talk about "going dry." Sophisticated coatings and the need to keep up with foreign manufacturing will supposedly push U.S. manufacturers to dry machining. But while dry milling and dry grinding may be growing in popularity, dry drilling is another matter.

Some people drill dry, but not very many. And certainly not high numbers of holes.

"It doesn't really exist in high-production operations," said Dr. John Sutherland, professor of mechanical engineering and director of the Center of Environmentally Responsible Manufacturing at Michigan Technological University, Houghton, Mich. He said that dry drilling currently is limited to operations involving cast iron and the production of shallow holes in certain steels and aluminums.

Chuck Petrosky, staff engineer for Solid Carbide Round Tools at the Kennametal Technology Center, Latrobe, Pa., agreed, adding that drilling presents unique challenges compared to other machining operations.

"[Drilling is] a continuous cut, whereas milling is an interrupted cut," he said. So, when a milling tool exits the cut, it has time to cool.

Even in drilling operations where coolant floods the hole, heat and friction can prevent the fluid from reaching the point of cut. Petrosky said that with no coolant to remove heat from the cutting surface, holes are likelier to close up, increasing the chances of drill breakage.

Another problem with running dry is that the chances of galling are greater. Besides cooling the tool, a metalworking fluid provides lubricity, which results in a cleaner finish and helps prevent galling.

Coating Is Key

Petrosky thinks that if dry drilling gains greater acceptance, it will be due to the continued development of advanced tool coatings. He cited titanium diboride as being a particularly good coating for drilling aluminum.

"It's a coating which aluminum doesn't adhere to," Petrosky said.

Another option is MOVIC, a "glide" coating developed jointly by Guhring of Germany and Vilab of Switzerland. MOVIC acts as a lubricating agent between the cutting tool and chip.

"MOVIC-coated tools produce about one-sixth the friction of TiN-coated tools," said Mark Megal, marketing manager for Guhring Inc., Brookfield, Wis. MOVIC is a nonstick industrial coating made of molybdenum disulfide. Megal said that MOVIC is akin to a surface treatment in that it impregnates the tool substrate rather than just coating it.

Thomas Friemuth, chief engineer and head of the manufacturing processes division at the Institute of Production Engineering and Machine Tools at the University of Hanover (Germany), said that coatings with a low friction coefficient and low thermal conductivity work best at isolating a tool from heat. He recommends TiAlN-based coatings for the dry drilling of ferrous materials.

Another key to successful dry drilling is ensuring adequate chip evacuation. Sutherland suggested using wide-flute drills, which allow chips to readily exit the hole. He cautioned, though, that the flutes shouldn't be too wide.

"The trick is to have plenty of room for the chips to evacuate without [undermining] the strength of the tool," said Sutherland. Dry drilling already subjects the tool to higher stresses than coolant-fed operations, and any compromise in strength could lead to breakage.

Kennametal Applications Engineer Mark Huston thinks that dry drilling may eventually move away from metal tools altogether. "There's the potential down the road for ceramic drills," he said.

A ceramic drill can withstand extreme heat and high speeds and compression while maintaining its cutting edge. But, Huston said, there are limited applications for ceramic drills.

"You have to have absolute rigidity and almost zero runout, because ceramic isn't very flexible," he said.

Have Europe and Asia Gone Dry?

Technical issues have clearly inhibited U.S. manufacturers from adopting, or even trying, dry drilling. That, apparently, is not the case overseas.

We've all heard that international manufacturers are leaving their U.S. counterparts in the dust when it comes to dry drilling. Do they really have a leg up on us? Probably. How did they do it? By learning to crawl before trying to run.

Petrosky said that his German colleagues have a different concept of "dry" than U.S. companies, and that they don't expect to go totally dry anytime soon. "They look at it more as reducing the use of coolant," he said.

Petrosky said that European manufacturers began by employing minimal-mist coolant techniques coupled with cold air and coatings to reduce their coolant use.

Friemuth disagreed, saying, "Our experiences are essentially based on purely dry drilling." He acknowledged that the range of operations available for dry drilling was limited, but added that feed and speed rates for those operations were the same as when performed with coolant. He said that there was virtually no loss of productivity when dry drilling tempered steels and low-to-medium-tensile-strength cast irons">gray cast irons.

Assuming that's true, why aren't U.S. manufacturers more interested in dry drilling? According to Sutherland, the lack of solid information regarding tool life, chip flushing and thermal stability keeps American metalcutters tied to coolant.

He also said that minimal-coolant applications, like those mentioned by Petrosky, would appeal to American manufacturers with high production rates and a strong desire to reduce their coolant use.

Sutherland said that some large U.S. automotive and aerospace manufacturers already use minimal-coolant techniques, but not as many as in Europe and Asia. He credited different political, economic and environmental controls, as well as the sheer size of the United States for the lukewarm interest in minimal-coolant techniques.

"We have a lot of room for waste products," said Sutherland. "If you're in one of the lowland countries in Europe and you have wastewater from cutting fluids, you have a bigger problem than you do here."

Sutherland also said that he thought Japanese manufacturers were more environmentally conscious due to their country's limited area, and that things might be different if the U.S. was a smaller country.

"I'm confident that if the entire population of the United States lived between Chicago, Tulsa and St. Louis, we'd figure out creative ways to do things, too," said Sutherland.

In the end, the real limiting factor for U.S. manufacturers going dry may be the nature of the industry itself. Some take an "if it ain't broke, don't fix it" attitude toward machining. Without environmental legislative pressures, some are hesitant to alter tried-and-true flood-coolant processes.

"Manufacturing is pretty slow to grasp certain things," Petrosky said. "Change doesn't come very quickly."

Cold-Air Guns Blast Heat

Heat buildup and chips are drill killers. So what do you do when coolant can't, or shouldn't, be used in a drilling operation? Stick to your guns.

Cold-air guns deliver a stream of air that's 50° to 80°F colder than standard compressed air. Most guns incorporate a vortex tube that converts air into two low-pressure streams: one hot and one cold. The hot air is directed out an exhaust port, while the cold air is sent down a flexible hose aimed at the point of cut.

Mike Rawlings, product engineer at air-gun manufacturer ARTX Ltd., Cincinnati, said that his company's product will cool a 0.500"-dia. drill running at 3,000 rpm, regardless of the depth of cut.

"It will work as long as you have some kind of pecking sequence," said Rawlings, who added that pecking is also necessary with most flood-coolant operations. The difference when using an air gun, though, is that there is no mess.

ARTX's basic system lists for $234 and includes 12" of flexible line, four generators to change the volume of air and a magnetic base.

Another cold-air gun manufacturer is Exair Corp., also in Cincinnati. Its basic unit costs $229. According to the company's applications engineer, Joe Panfalone, air guns are a good alternative to expensive mist systems. He conceded, though, that they're not the panacea for all applications.

"Water has 40 times more heat-carrying capacity than air," explained Panfalone. "But [using an air gun] is better than running dry." He added that a cold-air gun isn't a "product that's going to put the flood-coolant industry out of business. It's for specific applications."

He recommended air guns for operations in which the workpiece material could be damaged if exposed to coolant and for toolroom machines that can't be equipped with flood-coolant systems.

Panfalone said that cold-air guns could be used more than they currently are. He also believes that research on developing systems that combine cold-air technology and advanced tool coatings holds a lot of promise for improving metalcutting operations in the future.

- D. Phillips