It’s a seller’s market

It’s a seller’s market

Key industry sectors are experiencing strong demand— so strong that hamstrung manufacturers often can't keep up.n

The automotive, aerospace and automation industries are bellwethers of the U.S. economy. Today, the good news for companies in these industries is that customers want what they're selling. In many cases, however, that's a mixed blessing because of persistent problems that are keeping manufacturers from fully meeting customer demand.

Consider the automotive industry. Despite macroeconomic headwinds, such as high inflation and rising interest rates, the industry isn't suffering from a lack of demand. Instead, the difficulties are factors that have been constraining production.

"It's been one thing after another, from COVID in 2020 and then the semiconductor shortage beginning in 2021 and still lingering today," said Eric Anderson, principal research analyst at S&P Global Mobility in Southfield, Michigan, the automotive division of New York City-based S&P Global Inc., a provider of financial information and analytics. "We believe that through 2023, semiconductor flow will still determine what vehicle production is throughout North America and globally."

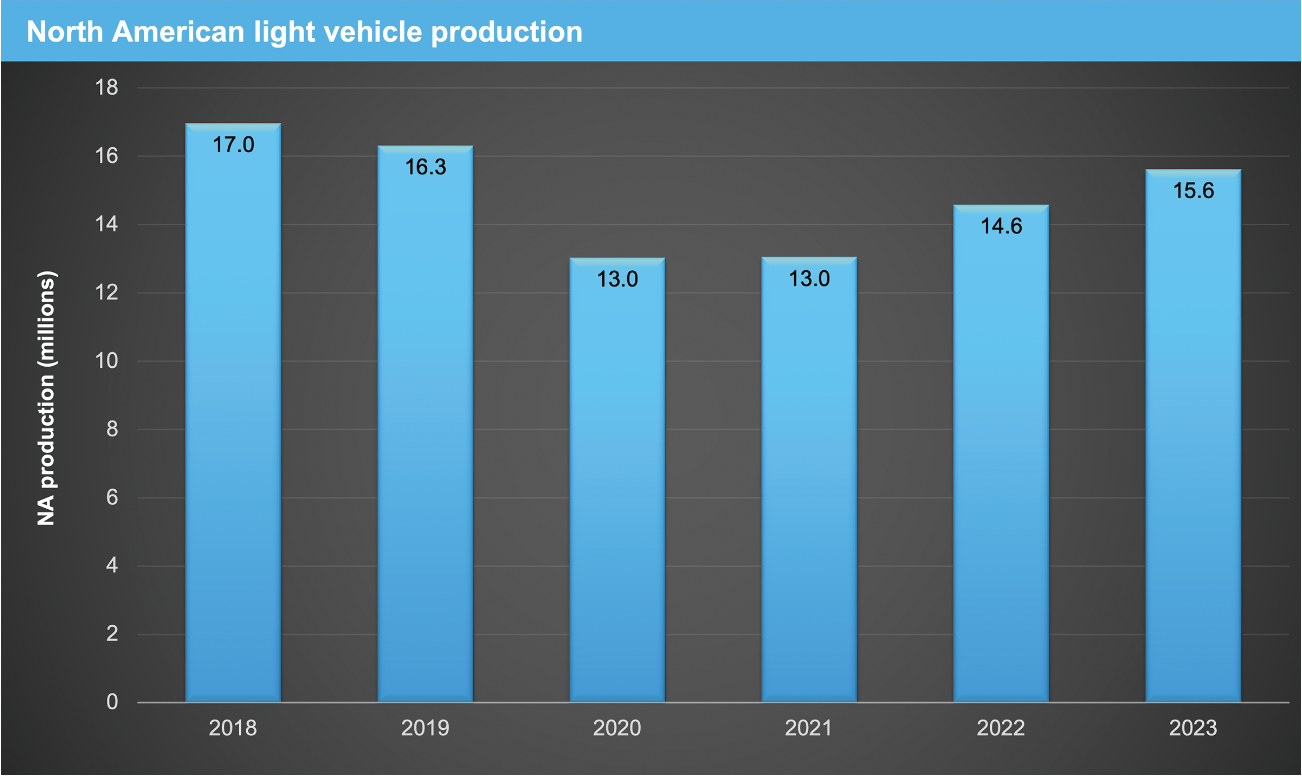

For now, he thinks that whatever number of vehicles manufacturers can produce will be sold due to pent-up demand on both the retail and fleet sides. For the past two years, he reports that North American production has been 13 million units, several million shy of normal output.

"Around the third quarter of last year was the most extreme amount of downtime and shutdowns we have seen for North America," Anderson said. "But each quarter over quarter, the semiconductor flow tends to improve a bit."

For 2022, he expects North American production to be about 14.6 million units, nearly a 12% increase over last year's figure, with production in the back half of the year exceeding that in the first half. Next year, he estimates that production probably will increase to 15.5 million units despite continued constraints due to semiconductor flow.

The graph shows that a rapid recovery to a pre-pandemic level is not expected. Semiconductor constraints through 2023 limit forecast figures for North American production, though the situation has been improving. Image courtesy of S&P Global Mobility

With semiconductors in short supply, Anderson said original equipment manufacturers have been diverting them to full-size pickups and SUVs at the expense of sedans and other less popular and less profitable vehicles. He expects that trend to continue for the remainder of this year and likely into next year as well until semiconductor flow returns to normal levels.

Prior to the COVID-19 lockdowns, he noted, U.S. vehicle dealers generally carried roughly 3.5 to 4 million units of inventory, which translated to about 70 days of supply.

With lockdowns in place, however, "you couldn't build vehicles," Anderson said. "And (with) the semiconductor shortage, we basically wiped out 3 million units of inventory. So almost 75% of the inventory has been depleted and has not been replenished."

Even when semiconductor supply normalizes, he doesn't expect dealer inventory to get back to 4 million units.

"OEMs have changed their perspective," Anderson said, "recognizing the higher profitability in carrying tighter inventories."

Nevertheless, he believes that an overbuild of 1 million to 1.5 million units still is needed to adequately replenish dealers, which he doesn't expect before 2024.

Significant Developments

In the meantime, Anderson reports that vehicle sellers and buyers are benefiting from a trend toward digital retailing in which, for example, sellers tell buyers that they don't have a desired vehicle today but that they can order it for delivery in two or three months. Sellers like this arrangement, he said, because they can acquire a customer even if the vehicle that the customer wants isn't available right away. In addition, he pointed out that OEMs selling this way usually don't need to incentivize as heavily as in the past. As for customers, he said they can order vehicles with the exact specifications they want, which is probably a reason for early indications that customer satisfaction with digital retailing is increasing.

Another significant development in the automotive industry is increasing demand for battery-powered electric vehicles. He said battery EV sales were only 1% of the total a couple of years ago but now are approaching 6%. Continued growth is expected over the next two years, he said, due in part to the United States' passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, which among other things seeks to incentivize the adoption of EVs.

On the supply side, Anderson continues to see heavy investment in battery EVs.

"OEMs are gearing up for their long-term electrification plans and how those products are going to fit in their portfolios," he said.

At present, Anderson said some OEMs are using "multi-energy" platforms to produce vehicles with internal combustion engines, as well as batteries. Most investment, however, has been directed toward all-electric skateboard architectures with a flat floor, he said.

"With the battery, you don't need an engine, transmission, oil pans and so forth, which opens up much more space within the vehicle," he said. "We're still in the earlier stages with some of these platforms. But it's something we expect to continue well beyond the next decade as OEMs continue to retool some of their facilities or in some cases go to all-new greenfield assembly plants to ramp up and launch battery electric vehicles."

At the same time, a totally new supply chain is being developed as OEMs begin to move away from the internal combustion engine.

"With many of the new skateboard platforms, it's an entirely new bill of materials," Anderson said.

Supply Headwinds

Like the situation in the automotive industry, the state of the aerospace sector is a two-sided tale.

"The demand side is excellent," said Richard Aboulafia, managing director of AeroDynamic Advisory LLC, an aerospace consulting firm in Ann Arbor, Michigan. "You've never seen such a strong recovery."

One major plus he cited is a record fiscal year 2023 U.S. budget for weapons procurement.

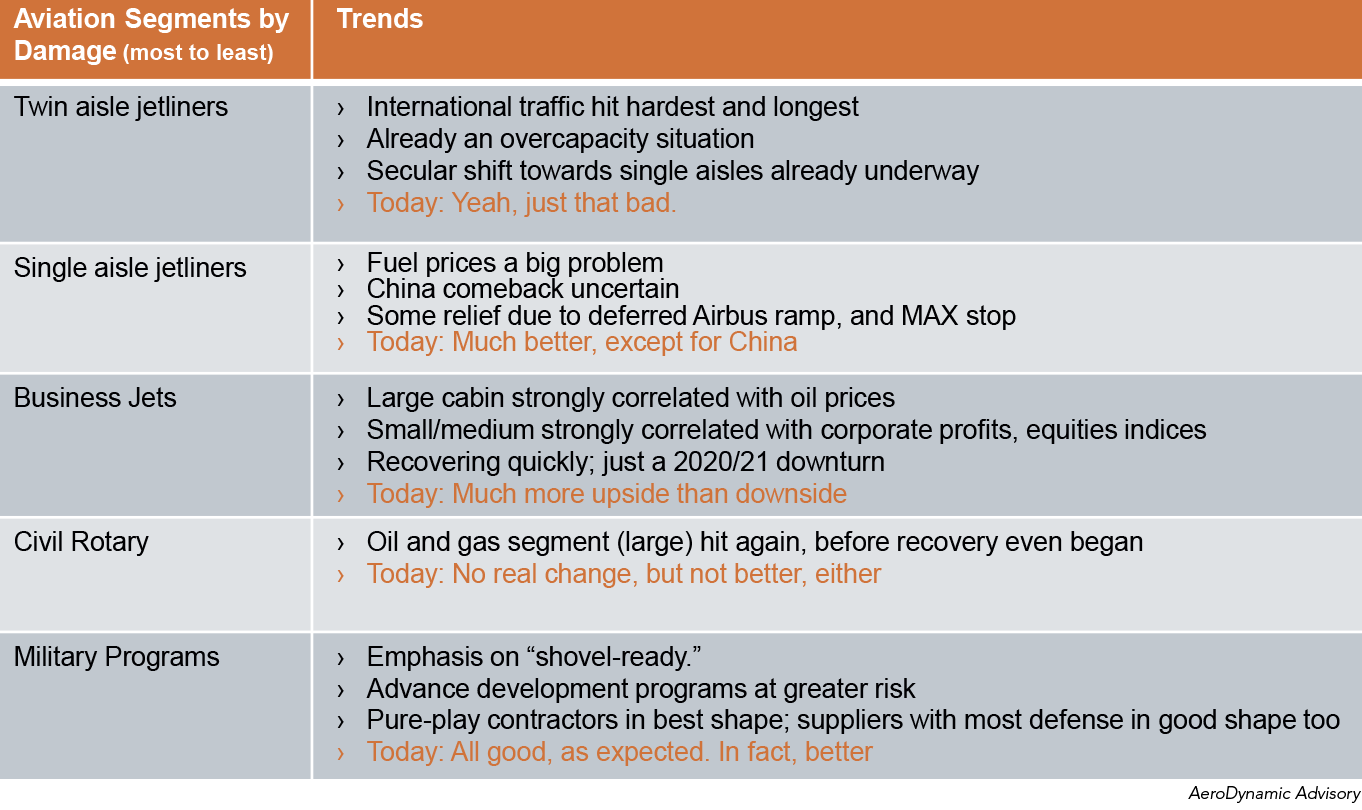

"We're heading close to $160 billion," Aboulafia said, "which is fantastic from an industry standpoint."As for commercial aircraft, he said demand is strong in every segment except twin-aisle jets. Wide-body demand is low because international travel has been the last to recover from the COVID-19-related slump, he said. In addition, he pointed out that many smaller single-aisle jets are doing jobs formerly done by twin-aisle jets.On the supply side, however, "we've got a steeper ride back than most other industries," Aboulafia said. "From a manufacturing standpoint, this is a $200 billion-a-year industry that was knocked down to just over a $100 billion-a-year industry."Besides COVID-19-related issues, a main culprit was the shutdown of Boeing's 737 Max line for a couple of years."In terms of supply, things are a mess — as messy as they were a year ago, maybe even more messy," Aboulafia said. "There are serious problems getting things out the door."As an example, he pointed to what he called the biggest program in aerospace: production of the Airbus A320.The company is trying to boost A320 production to 65 per month in a year or two, up from a low of 40 per month, Aboulafia said, "but there are enormous hurdles on the way to getting there."In the defense segment, he said the biggest program is the production of Lockheed Martin's F-35 fighter aircraft."We were supposed to be at 156 planes this year," Aboulafia said, "but it looks like we're going to be stopped short of 150, in the high 140s."He said major manufacturing problems include difficulty finding personnel and supply chain issues, such as the inability to obtain sufficient quantities of castings and forgings. This particular shortfall, he said, can be blamed on recent diplomatic difficulties with Russia, the world's largest supplier of titanium sponge, as well as castings and forgings made of the material. He reports that U.S. companies have stopped buying Russian titanium. And while Europeans still purchase it, there are concerns about a cutoff.In addition, Aboulafia said roadblocks are in the way of lining up alternative suppliers."Not everyone is willing to invest in new tooling, mills and casting facilities," he said. "Because if the problem with Russia is resolved, then the business case for this new investment evaporates."For 2022, Aboulafia forecasts an industry expansion of about 17%."That's certainly good, but it would be a heck of a lot better if it weren't for supply chain constraints," he said, adding that heexpects these constraints to continue for another 12 to 18 months.Although Aboulafia doesn't see any major technological disruptions on the horizon, he did point to a couple of developments in the aerospace industry. One is that over the past year, it has become clear that the military aircraft market will change with the introduction of Loyal Wingman combat aircraft. He describes these as smaller, pilotless combat planes that accompany and are controlled by a piloted fighter."There might be one, two or a dozen companions (that) extend the fighting power of a traditional fighter," he said. "It's a big change, but you're not going to see metal cut in any meaningful way for another dozen years."Another development is electrification of aircraft, such as small, very short-range helicopters designed to lift people out of urban areas."Electrification is happening very slowly in some segments, but it's going to be a very long road and might not be relevant to the overwhelming bulk of the industry," Aboulafia said. The reason is that for the most part "batteries just don't have the kind of power density needed to drive an aircraft."Robots on the MarchAircraft and automotive sales may be languishing due to supply chain constraints, but that's not the case in the automation industry. For three consecutive quarters, North American robot sales have hit record highs, according to the Association for Advancing Automation in Ann Arbor, Michigan.For CNC machining in particular, orders for automation are "beyond expectations," said Craig Zoberis, founder and president of Burr Ridge, Illinois-based Fusion | RoboJob-USA, which provides systems for automatically loading and unloading CNC turning and milling machines.During a night shift, two Mill-Assist systems with traditional Fanuc industrial robots tend Haas VF-2SS CNC mills unattended. Image courtesy of Fusion | RoboJob-USA

He said one reason that business is booming for firms like his is that machine shops are overbooked due in part to increased interest among manufacturers in "right shoring" machining — that is, having precision-machined parts made in the United States for U.S. consumption — in the wake of the pandemic, during which many U.S.-based OEMs that sent machining work outside the country lost control of the process.

In addition, Zoberis pointed to a spike in interest during the pandemic in switching from CNC machine tending by operators to automated machine tending.

With the pandemic receding, interest among shops is "still the same or higher," he said. "It's like they've got a bunch of Ferraris in their shops and they're finding that their spindles are underutilized, so they're looking at ways of trying to automate as quickly as possible to stay competitive."

Currently, one popular way of doing this is with what Zoberis calls purpose-built robotics: ready-to-purchase systems that include a six-axis robot and related hardware and software, all designed for a particular application.

"We're offering off-the-shelf, turnkey solutions for small-to-medium-size companies that normally wouldn't see this as an affordable solution," he said, adding that he expects 40% to 50% growth in demand for these purpose-built systems in 2023.

In addition to systems for CNC machine tending, Zoberis said the main categories now are systems for welding, palletizing and sheet metal fabrication.

These systems are examples of what he sees as a new "productization" of robotics.

"This is changing the landscape because you don't necessarily need a custom or engineered solution where you hire an integrator to come in and do a scope of work and determine what you need," Zoberis said. "Now there's a catalog of purpose-driven products for (different) operations."

For more information about trends in automation from Fusion | RoboJob-USA, view video presentations at https://qr.ctemag.com/1dhdi