Soaring aerospace parts

Soaring aerospace parts

With a global commercial aircraft order backlog recently valued at $920 billion, jetliner and jet-engine builders are placing volumes of part orders not seen for many years -- if ever.

To understand just how healthy the market for new commercial jetliners is, pay a visit to the desert where the old ones go to die. Over the past 5 years, U.S. airlines have retired nearly 1,300 planes, or 21.7 per month, to various desert storage areas, according to an Associated Press report. In the past, these planes might have been lined up neatly in rows, sealed and returned to service when airline traffic increased. Now, many of them are going straight to the desert scrap heap in favor of new, more fuel-efficient jets.

Indeed, airlines around the world are on the biggest-ever binge of commercial jet buying, ordering more than 8,200 new planes over the past 5 years from Airbus and Boeing alone, according to AP.

"The most important theme in aerospace is the unprecedented growth spurt in the civil aviation market," said Richard Aboulafia, vice president of analysis for Teal Group Inc., an aerospace and defense consulting firm based in Fairfax, Va., during a presentation at the AMT Global Forecasting & Marketing Conference, held Oct. 14-16 in Cincinnati. "It's astonishing, and while I am concerned that a lot people are banking on these growth rates continuing and would advocate a more conservative approach going forward, it's been a great ride. This is a big business at its peak."

Parts Bonanza

With record-setting order backlogs, jetliner and jet-engine builders are placing volumes of part orders not seen for many years—if ever. "It's a giant tsunami just brewing," said Kevin Flanagan, director of sales and marketing for Glastonbury, Conn.-based Flanagan Industries LP, a jet-engine parts maker, in an article by the Hartford Courant.

Business information provider Bloomberg LP, New York, reported that in September the global commercial aircraft order backlog was valued at $920 billion. Jet-engine builder Pratt & Whitney, East Hartford, Conn., expects to double engine production from current levels by the end of the decade.

Another aerospace parts manufacturer, Pegasus Manufacturing Inc., Middletown, Conn., will be adding a shift to meet demand for aerospace parts, according to the Hartford Courant. The company expects to double its revenue by 2018 and more than double its staff, from 75 to about 175. The shop also expects to log 340,000 man-hours when production peaks in 2018. In 2013, Pegasus logged 90,000 man-hours.

Civil Sensation

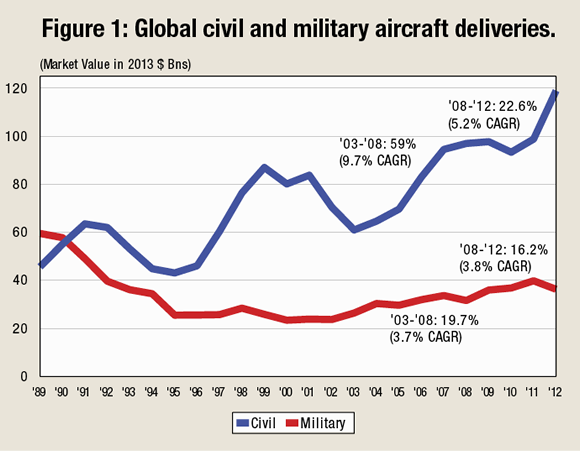

A huge portion of the parts made by aerospace suppliers are going into civil aircraft, which have grown to dominate the aerospace industry compared to military aircraft (Figure 1). For example, in 2012, the market value of global civil aircraft deliveries reached $118.9 billion, compared to just under $36.7 billion for military aircraft deliveries, according to Teal Group. Compare that to 1989, when the military aircraft segment was top dog, at about $60 billion, while civil aircraft deliveries brought in under $50 billion (all figures are calculated in 2013 dollars and based on actual, not list, prices).

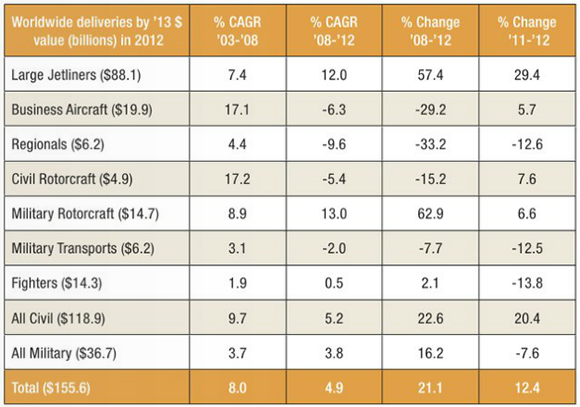

At $88.1 billion, large jetliners accounted for the vast majority of 2012 civil deliveries, more than doubling its total of $40 billion in 2003. What's more, the large jetliner market continued to grow through the Great Recession.

"As we all know, in 2009 the global economy declined, and that should have precipitated something bad in the jetliner [building] market," Aboulafia said. "But, like the proverbial Energizer Bunny, it just kept going."

From 2008 to 2012, which includes the Great Recession and the sluggish economic recovery that followed, large jetliner deliveries shot up 57.4 percent, even while business aircraft deliveries dropped 29.2 percent, regional jets fell 29.2 percent and civil rotorcraft dipped 15.2, according to Teal Group (Figure 2).

'Rip in the Fabric'

"What is different is that there has been a blatant rip in the fabric of the jetliner universe," Aboulafia said. "We've never seen this massive bifurcation between the cost of fuel and the cost of cash, which used to rise and fall in tandem. Look at it from the airlines' perspective. Interest rates for loans to buy jets are very low. In the past, when oil was $25 a barrel, why [should the airlines] bother replacing jets? Their fully depreciated DC-9s were looking great, the passengers weren't complaining, so why not keep them in service?"

However, today's oil prices are nearly four times that figure, at $95 per barrel. In times past, when fuel was expensive, interest rates on loans were expensive too, and airlines typically could not afford to pay for a retooled fleet. "But over the past 5 years, for the first time ever, when airlines really wanted to replace old, fuel-guzzling jets because oil was over $100 a barrel, they could get low-interest loans," Aboulafia said. "And there's also a third factor here: From a third-party capital provider standpoint, [when these loans were being made] there really weren't many other games in town [where capital could go]: emerging markets, real estate, technology stocks—no one wanted them." Historically, large jetliner financing and leasing has been a stable, reliable market, so the money poured in.

Figure 2. Aircraft markets from 2003 to 2012.

"If [an airline] gets rid of DC-9s and replaces them with new Boeing 737s or Airbus A320s, the fuel and maintenance savings are actually greater than the lease cost of the new jets," Aboulafia said. "You'd have to be an idiot not to do it."

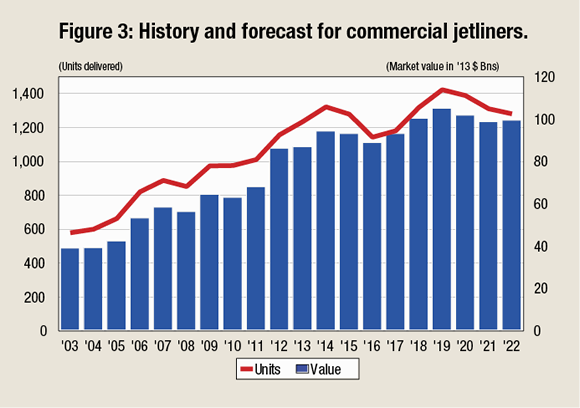

While some industry observers see an "asset bubble" building in the commercial jetliner industry, one that might lead to a crash in demand, Aboulafia doesn't. "It's a little frothy maybe, but not a bubble. We're building a lot of planes, but they are being profitability flown on routes." Instead, he sees "a really nice plateau" from 2014 to 2022, where each year about 1,200 large jetliners will be delivered with a total annual value of about $100 billion (Figure 3).

Trickle-Down Margin Pressure

Because Boeing and Airbus have ramped up jetliner building, they need to keep production levels high to avoid losing money, according to Aboulafia.

"What appears to have happened is the manufacturing guys [at Boeing and Airbus] are looking at what will happen to their manufacturing cost assumptions if they drop by a third in production. As a result, the builders are discounting heavily on list prices for existing models," he said. "The first thing you should know about jetliner list prices is they are the greatest work of fiction since Dr. Seuss. You get 40 percent off list for showing up and wearing a tie. For narrow-body jets, actual prices have historically been 45 to 50 percent off list."

Today, Boeing and Airbus manufacturing managers and their sales departments are debating the merits of discounting even more—up to 70 percent—rather than risk major production problems caused by a lack of orders. "They are emphasizing dropping prices to keep moving metal out the door," Aboulafia said.

What does this mean for the machine shops and part manufacturers selling to Airbus or Boeing? Plenty. "This pressure gets translated directly downhill, squeezing margins," Aboulafia said. "Suppliers of machine tools, for example, will be under a lot of pressure for the next couple of years to get through the valley to the other side, when Boeing and Airbus start building second-generation planes."

Another challenge for suppliers will be the type of parts and systems used on next-generation jetliners. "I've never seen anything like this in 25 years on the job," Aboulafia said. "There is an unprecedented amount of new technology and new models coming out, and from the standpoint of tooling, there should be great opportunities for suppliers. When the 777X is launched, it will look like a regular 777 and will target the same market segment, but it will be a completely different industrial reality. So from the supplier standpoint, there are unprecedented technical challenges, as well as the challenge of coming up with the risk-sharing capital needed to meet Airbus' and Boeing's demands for developing new technology."

The 777X will blend old and new technology. According to Boeing, it will feature new extended horizontal stabilizers and a 7 ' (2.14m) longer fuselage, bringing it to 250 ' (76.2m). New composite-fiber wings will be 234 ' long (71.3m), up from 212 ' 7 " (64.8m). Folding 11 ' (3.35m) wingtips will allow 777X models to use the same airport gates and taxiways as earlier 777s. The plane will also be lighter, at 759,000 lbs. (344,277 kg), compared to the 775,000-lb. (352,000 kg) original 777 and will use the new GE9X jet engine from GE Aviation.

The mostly aluminum 777X airframe will include composite materials comprising 9 percent of the structural weight, much less than the 787, in which composite materials account for 50 percent of structural weight. The 777X will burn 12 percent less fuel than the 777-300ER, according to Bob Feldmann, vice president and 777X program manager for Boeing. The company officially launched the 777X at the 2013 Dubai Airshow in November, announcing a total of 259 orders worth more than $95 billion in list prices.

Battle for the 777X

Nothing better illustrates the economic power of the commercial aerospace industry than the battle over where the revamped Boeing 777X will be built. In November, the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers District 751 local turned down Boeing's contract offer to build the 777X, because the pact required major concessions by the union. Soon after, Boeing began accepting bids from other regions to build the plane, and no fewer than 21 states began falling over each other to offer tax breaks, worker training and other incentives to move 777X production to their states.

The bidding war convinced enough union members at District 751 to change their votes to yes on a slightly improved contract in a second vote in January, and the contract was narrowly approved, keeping the 777X manufacturing jobs—and jobs at machine shops that do business with Boeing—in Washington state, for now. Such are the benefits for Boeing of having a high-profile, successful U.S. manufacturing success story. CTE