Teflon on steroids

Teflon on steroids

The creation of superhydrophobic metals using femtosecond lasers.

People realize the benefits of hydrophobic, or water-repelling, metals when cooking bacon and eggs in a nonstick frying pan. However, those pans need to be tilted about 70° before the fluids roll off the surface, and the hydrophobic properties fade when the chemical coating eventually wears or peels off.

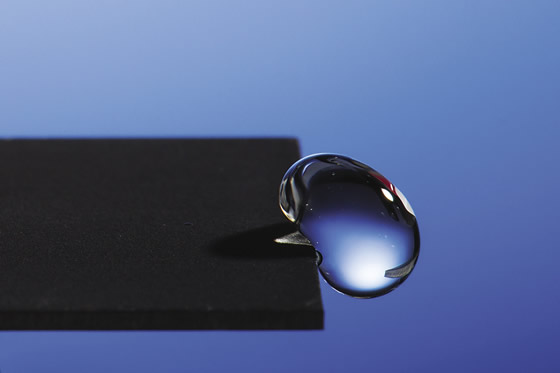

To overcome the need for temporary coatings, researchers at the Institute of Optics at the University of Rochester have developed superhydrophobic metals using a femtosecond laser to finely etch structures into metal. With powerful pulses that last on the order of a millionth of a billionth of a second, the laser creates microgrooves, on top of which densely grouped, lumpy nanostructures form. Compared to a Teflon surface, the laser-etched surface exhibits much stronger hydrophobicity and requires only a couple degrees of tilt for water to slide off, said Chunlei Guo, a professor of optics at the university.

The Guo research team at the University of Rochester uses femtosecond lasers to create nano- and micro-structures on a metal surface and make it superhydrophobic.

The researchers have produced superhydrophobicity on platinum, titanium, brass and steel. "I believe with additional research we can create superhydrophobicity on most metals and possibly other materials as well," Guo said.

"The materials are so strongly water-repellent, the water actually gets bounced off," he said in an article the university published about the research. "Then the water lands on the surface again, gets bounced off again, and then it will just roll off the surface."

Guo explained that the tiny structures trap air to prevent water from infiltrating the space and reduce the surface area that comes in contact with water. This causes the water molecules to bead up and bounce off the surface while collecting dust particles that are present.

Outside the laboratory, superhydrophobic metals could resist rust and prevent icing and biofouling, enabling them to keep ice off of airplane wings and tails, for example, without the need for deicing, according to Guo. And in regions where water is scarce, a latrine that incorporates superhydrophobic materials could remain clean with minimal water flushing.

In addition, the laser-etched structures turn shiny, reflective metal surfaces black, making them highly efficient at absorbing light. Guo noted this could lead to more efficient, low-maintenance solar collectors and sensors.

However, it takes about an hour to pattern a 1 "×1 " (25.4mm × 25.4mm) metal surface, Guo stated. To scale up the process, the researchers are working on optimizing the femtosecond laser and processing procedures for industrial applications.

For more information about Guo's research team at the University of Rochester, call (585) 275-2134 or visit www.optics.rochester.edu/workgroups/guo.