Of all machining processes, wire EDMing is perhaps best suited for lights-out manufacturing. No chips get in the way. There are no worries about cutting tool wear or breakage. And if a wire breaks or shorts out, the machine tries to rectify the problem before notifying a human that it needs help. This allows tool and die makers and an increasing number of traditional machine shops—especially those serving the aerospace and medical industries, where wire EDMing is used to cut otherwise unmachinable part features—to significantly boost available machine time while reducing labor costs.

Tap, Tap

Unfortunately, the one thing that can go wrong might actually break the machine tool. When a slug comes loose, it can fall into the lower nozzle and cause damage or become jammed between the head and workpiece. One inelegant solution is so-called slugless EDMing, in which the wire vaporizes the slug, but this eats up huge amounts of time, wire and electricity. Small metal tabs can be left to support the slug until the next morning, but removing them requires additional processing and human intervention.

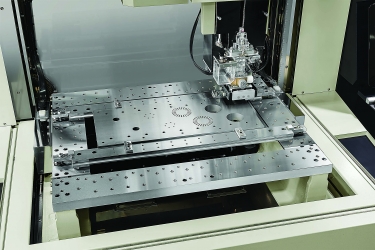

GF Machining Solutions’ ASM system uses compressed air to lift and remove just over a ½-lb. slug, which then is deposited into a basket at the side of the machine. Image courtesy of GF Machining Solutions

Steve Raucci, EDM product manager at Methods Machine Tools Inc., Sudbury, Massachusetts, offers a solution. He said the Core Stitch function on FANUC RoboCut α-CiB series wire EDMs retains slugs in the workpiece via a reverse discharge “brass adhesion” process, leaving small islands of soft material that hold slugs in place. After roughing, a few light taps with a plastic or brass hammer are enough to separate a slug, whereupon the operator can return the workpiece to the wire EDM for final machining if necessary.

A hammer helps achieve lights-out machining because, for starters, Core Stitch eliminates the need to stop a machine and apply electrically conductive glue or magnets to hold slugs, automating what was once a manual function. As Raucci explained, the tapping function itself also can be automated.

“We have an aerospace customer that’s using a FANUC robot as part of a machining cell,” he said. “The robot removes a jet engine component from the EDM and sets it on a slug removal station. It then exchanges its grippers for a brass punch, knocks out the slugs and places the part back into the machine for a final skim pass.”

Slugging It Out

GF Machining Solutions LLC, Lincolnshire, Illinois, takes a different approach to wire EDM slug management. EDM Product Manager Eric Ostini said the company’s AgieCharmilles Cut P series wire EDMs can be equipped with an automated slug management mechanism that uses a Venturi-style vacuum to basically suck slugs out of a workpiece.

FANUC America’s Core Stitch function uses a reverse discharge process to retain slugs in the workpiece. They then can be removed with a few light taps from a hammer. Image courtesy of Methods Machine Tools

“As the slug breaks free, it’s supported by the lower head while the upper head lifts up and out of the way, allowing the attached ASM mechanism to move into position,” he said. “The ASM uses compressed air to generate enough suction to lift and remove just over a ½-lb. slug, which is then deposited into a basket at the side of the machine. The upper head then returns to its previous position and either finishes the cavity or moves on to the next one, all completely lights out.”

An unattended machining strategy, however, requires more than automated slug removal. Flawless automatic wire threading is also needed. FANUC America Corp., Rochester Hills, Michigan, addresses this with its revamped AWF3 automatic wire feed system. Raucci said the new threader includes an integrated air supply that runs the length of the annealing tube, allowing the machine to thread while fully submerged, even at the maximum 20" Z-height.

“It’s very accurate,” he said. “We can thread a 0.01" wire, for example, through a 0.015"-dia. hole and are able to feed the wire through much taller kerfs than the previous generation. Couple that with the machine’s automated probing, coordinate rotation, remote management features and extreme reliability, and it means you can load it up with a 66-lb. spool and come back 100 hours later to a pile of finished parts.”

Trust, but Verify

Because robust threading is important, Ostini said GF Machining Solutions created its Threading-Expert and automatic wire changer systems. But just as important is knowledge of wire breaks and other process-related events. That is why the company has developed eTracking software that constantly monitors and records the spark condition related to specified norms, generator parameters and maintenance and alarm status, providing full traceability of mission-critical components.

“It also provides an area where step-by-step work instructions are presented to the machine operator, which will not allow the machine to start unless the operator verifies that each step was performed,” he said.

Makino’s UP6 Heat wire EDM boasts 1μm precision across its entire 25.6"×18.5" working area. Image courtesy of Makino

Makino Inc., Mason, Ohio, is another wire EDM builder that recognizes the need for efficient, predictable lights-out machining. Brian Pfluger, EDM product line manager, noted that his equipment easily checks the dependable threading box thanks to a jetless threading system, which is reportedly able to thread through 4" of kerf with 100% reliability. He also said smaller slugs are manageable with Makino’s dual-pump, independently programmable flushing system. Yet he’s quick to point out that shops must have several other critical functions in place before turning out the lights.

To achieve no-fail remote monitoring and data collection, wire EDMs should have hard-wired network connections, not wireless. Pfluger said this will avoid the “electronic hell” created by EDM spark generators. Highly accurate, repeatable, automation-ready workholding also is needed. But it’s the accuracy of the machine tool that he said is the main ingredient for predictable unattended EDMing.

“An increasing number of shops are asking us about automation, but my response is that a high-quality, highly accurate machine tool must be in place first,” he said. “This means a machine with the requisite mass and thermal stability for round-the-clock operations. It should have positioning and feedback systems suitable for the parts being produced. And just as important are consistent, reliable processes. Automating inefficient or unpredictable ones will lead to poor results.”

More Accurate, No Recast

One example of this is Makino’s UP6 Heat. Though designed with progressive stamping die manufacturers in mind, the wire EDM’s 1μm precision across its entire 25.6"×18.5" working area should be of interest to anyone producing extremely accurate parts in an unattended fashion.

Makino also offers the HyperDrive system, which helps improve straightness and accuracy, particularly in small part details, Pfluger said.

Robotic part handling is increasingly popular with job shops and others seeking to automate wire EDM processes. Image courtesy of MC Machinery Systems

The good news for shops looking to automate wire EDMing is that a wide range of high-quality machine tools and options are available, all of which make the leap to lights out much easier. Evan Syverson, additive business

development manager at Sodick Inc., Schaumburg, Illinois, said EDM technology has made significant strides in recent years, making it a viable machining process for manufacturers that once worried about EDM-generated recast layers and suboptimal surface quality.

He pointed to increased use of electrolysis-free power supplies together with glass scale feedback, linear motors, ceramic components and servo-controlled wire tensioning as the key drivers behind these improvements. The developments make wire EDMs, such as Sodick’s ALN series, more accurate and better able to impart extremely fine surface finishes.

On the automation side, Sodick’s Super Jet AWT high-speed threading and wire tip disposal units

reduce operator intervention.

“The tables have definitely turned with wire EDM,” Syverson said. “It’s become far more mainstream, and shops are looking for ways to automate it, just as they are for their other machine tools.”

Mike Bystrek, EDM applications and national wire EDM product manager at MC Machinery Systems Inc., Elk Grove Village, Illinois, agreed, saying the company’s MV2400-ST Advance Type wire EDM is an excellent example of state-of-the-art EDM technology.

“The new M800 control platform enables us to offer a pedestal option, providing easy mobility and access to any position near the machine for flexibility in automation layouts or safety purposes,” he said. “It also offers enhanced setup and maintenance functions that greatly reduce downtime, as well as remote management features for unattended machining.”

No-fail wire threading is a prerequisite to any lights-out wire EDM operation. Image courtesy of Sodick

One of these new control features is a built-in scheduler.

“The scheduler allows the operator to easily change the order of operations of the workpieces while machining,” Bystrek said. “This type of flexibility is crucial when maximizing your attended operation.”

Like Pfluger, Bystrek suggested that shops would do well to look beyond the wealth of available machine tool and control features and focus instead on internal processes and the capabilities needed to support them.

“It’s also important to have a very good team, a team that includes at least one—and preferably more than one—EDM expert on staff,” he said. “A lot of companies don’t have this, especially those without a long history of EDM use. In lieu of this, shops should look for a machine tool partner that’s able to support them with knowledge and advice that will help them develop sound machining processes and the equipment needed to execute those processes. Without that, the only thing automation is going to do for you is make bad parts more efficiently.”

Contact Details

Contact Details

Contact Details

Contact Details

Contact Details

Related Glossary Terms

- annealing

annealing

Softening a metal by heating it to and holding it at a controlled temperature, then cooling it at a controlled rate. Also performed to produce simultaneously desired changes in other properties or in the microstructure. The purposes of such changes include improvement of machinability, facilitation of cold work, improvement of mechanical or electrical properties and increase in stability of dimensions. Types of annealing include blue, black, box, bright, full, intermediate, isothermal, quench and recrystallization.

- electrical-discharge machining ( EDM)

electrical-discharge machining ( EDM)

Process that vaporizes conductive materials by controlled application of pulsed electrical current that flows between a workpiece and electrode (tool) in a dielectric fluid. Permits machining shapes to tight accuracies without the internal stresses conventional machining often generates. Useful in diemaking.

- feed

feed

Rate of change of position of the tool as a whole, relative to the workpiece while cutting.

- kerf

kerf

Width of cut left after a blade or tool makes a pass.

- tap

tap

Cylindrical tool that cuts internal threads and has flutes to remove chips and carry tapping fluid to the point of cut. Normally used on a drill press or tapping machine but also may be operated manually. See tapping.

- tapping

tapping

Machining operation in which a tap, with teeth on its periphery, cuts internal threads in a predrilled hole having a smaller diameter than the tap diameter. Threads are formed by a combined rotary and axial-relative motion between tap and workpiece. See tap.

- threading

threading

Process of both external (e.g., thread milling) and internal (e.g., tapping, thread milling) cutting, turning and rolling of threads into particular material. Standardized specifications are available to determine the desired results of the threading process. Numerous thread-series designations are written for specific applications. Threading often is performed on a lathe. Specifications such as thread height are critical in determining the strength of the threads. The material used is taken into consideration in determining the expected results of any particular application for that threaded piece. In external threading, a calculated depth is required as well as a particular angle to the cut. To perform internal threading, the exact diameter to bore the hole is critical before threading. The threads are distinguished from one another by the amount of tolerance and/or allowance that is specified. See turning.

- turning

turning

Workpiece is held in a chuck, mounted on a face plate or secured between centers and rotated while a cutting tool, normally a single-point tool, is fed into it along its periphery or across its end or face. Takes the form of straight turning (cutting along the periphery of the workpiece); taper turning (creating a taper); step turning (turning different-size diameters on the same work); chamfering (beveling an edge or shoulder); facing (cutting on an end); turning threads (usually external but can be internal); roughing (high-volume metal removal); and finishing (final light cuts). Performed on lathes, turning centers, chucking machines, automatic screw machines and similar machines.

- wire EDM

wire EDM

Process similar to ram electrical-discharge machining except a small-diameter copper or brass wire is used as a traveling electrode. Usually used in conjunction with a CNC and only works when a part is to be cut completely through. A common analogy is wire electrical-discharge machining is like an ultraprecise, electrical, contour-sawing operation.

Contributors

GF Machining Solutions LLC

847-913-5300

www.gfms.com/us

Makino Inc.

513-573-7200

www.makino.com

MC Machinery Systems Inc.

630-616-5920

www.mcmachinery.com

Methods Machine Tools Inc.

877-668-4262

www.methodsmachine.com

Sodick Inc.

888-639-2325

www.sodick.com