Poly – Poly – or what? Part 9: Lach Diamant Goes East

Poly – Poly – or what? Part 9: Lach Diamant Goes East

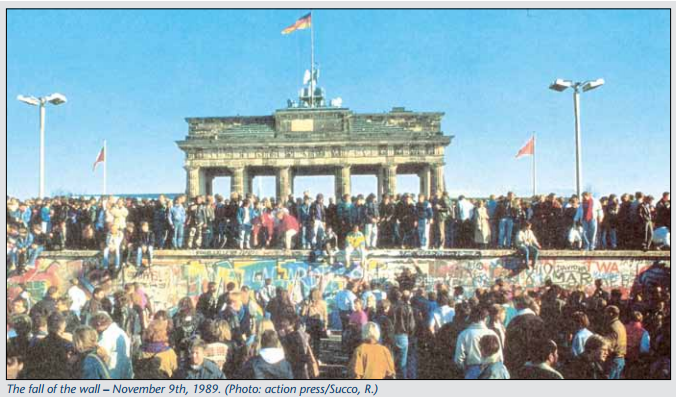

No, this story does not begin with "once upon a time," since it is far too serious, vivid and full of unique facts for a fairy tale. The German partition created different living conditions in both parts of Germany. Moreover, since August 13, 1961, when a dividing wall was built, the citizens in the Eastern part were deprived of any possibility to move to the West. Thus, living conditions and priorities could develop in a contrary direction under totalitarian control.

No, this story does not begin with "once upon a time," since it is far too serious, vivid and full of unique facts for a fairy tale.

The German partition created different living conditions in both parts of Germany. Moreover, since Aug. 13, 1961, when a dividing wall was built, the citizens in the East were deprived of any possibility to move to the West. Thus, living conditions and priorities could develop in a contrary direction under totalitarian control.

The West successfully celebrated free market economy, the East fought more and more for foreign currencies in order to survive. Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski, the master of currency procurement, gave industrial plants, or rather the heavy industries that were selected for obtaining foreign currencies, highest priority.

There was practically no brand competition in East Germany – compared to the neighbouring West – and thus the citizens experienced long, cumbersome delivery times for everyday necessities.

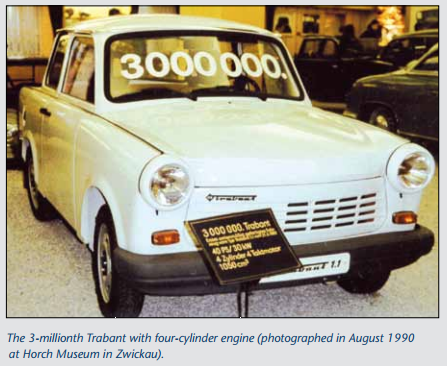

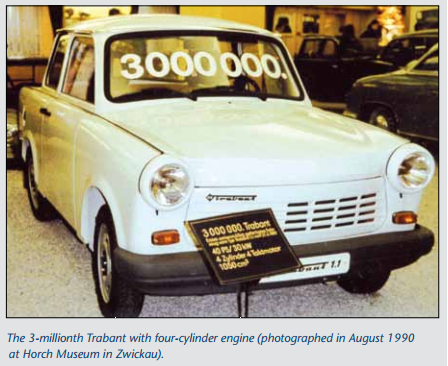

For example, the wait time for a new washing machine was three years and up to 14 years for a car. In the latter case, only the so-called "Trabi" (Trabant) and Wartburg were available choices, both featuring only minor enhancements over decades. It was certainly not the fault of East Germany's (desperate) engineers. There were enough ideas within the automobile industry of the East: Starting with a modern hatchback body to common rail diesel technology.

Just a few years ago, there was a discussion whether East Germany (GDR) had invented the VW Golf, which, however, is not true (Focus 10/2014). At the end of the 1980s, there were only approximately 200 cars per 1,000 residents; in the West were twice as many. It is not surprising that in 1977, the SED (Socialist Union Party of Germany) regime decided to buy 10,000 VW Golfs. VW CEO, Tony Schmücker, hoped for on-going business and follow-up orders. That was not the case.

VW engines for the East

The VW plants in Hanover and Salzgitter had two assembly lines for smaller engines. Both were insufficiently utilized. Simply put, one too many – and the GDR needed one.

According to the magazine Spiegel 7/1984, CDU politician and VW board member Walther Leisler-Kiep initiated the deal with the GDR. Details of this plan, not requiring payment in foreign currencies by GDR, came from the former VW manager Hahn. The initial offer and project were presented in June 1982 in East Berlin. When subsequent experiments showed that the VW engines could easily be built into Wartburg and Trabi automobiles, this was a breakthrough and the deal was on. According to the plan, VW should assemble a complete production line for the GDR by 1988, with an annual output of 290,000 engines. In return, Wolfsburg would deliver a total of 15,000 VW transporters by 1993. All in all, it was only a 600 million Deutsche Mark business, but Hahn predicted "this will be a long-running deal."

Everyone was convinced that the Volkswagen group would now become the most important facilitator of the planned modernization of the East German automobile industry. Up to this point, both Wartburg, produced in Eisenach, and Trabi, produced in Zwickau – still featuring two-stroke engines – were completely out-of-date: Low performance, excessive fuel consumption, in addition to a negative environmental impact.

Farewell to the Tuk-Tuk of Two-Stroke Engines?

From 1988 onwards, the assembly line, delivered by VW, was meant to only built water-cooled four-cylinder, four-stroke engines into GDR cars. A newly built plant in Chemnitz should build the engines, previously propelling the VW Golf, with 40 or 55 hp (1,100 or 1,300 cm3 capacity); the same applied for a diesel version.

About 190,000 engines were meant to be built for domestic demand, another 100,000 for VW. Finally, in October 1988 – after the end of the autumn trade show in Leipzig – the beginning of a new era for the GDR automobile industry could take its course, as planned in 1984.

In addition to delivery problems, noticeable not only during plan realization for accessory components, the industry was also behind schedule for the delivery of the old-style models. On top of that, GDR citizens soon were disillusioned and disappointed after the first cars with four-cylinder engines were delivered. A new engine simply does not make a new car.

The unproportionally high price for e. g. a Wartburg of over 30,000 East Mark also discouraged many potential buyers. Most could not afford this. Only the privileged upper class, high officials or a few craftsmen could purchase at this price.

New Technological Insights

Delivery and initial start-up of the VW provided assembly line for the four-stroke engines gave both engineers and workers for the first time broad-based technological insights, which, up to this point, had not been accessible.

Above all, as an example, the machining and cutting of aluminium in engine and accessory production, which finally brings us to the topics of diamonds and "Poly – poly – or what?"

Polycrystalline cutting inserts, available in the Western industry since 1973 (see Poly – poly – or what? series, part 1), were either unknown or, due to lack of foreign currencies, unavailable to GDR tool manufacturers. Machining of nonferrous metals, such as aluminium and copper, and composites relied on available carbide tools or pressed diamond or PCBN composite round blanks from the former USSR.

However, these "cutting heads" had one fundamental disadvantage: Compared to the successful product "compax" – at this time offered by the diamond manufacturer General Electric – they could not be soldered – the necessary carbide base for successful soldering was missing (see Poly – poly – or what? series, part 2, composite material Elbor).

As apparent from the attached research report, drawings and the case histories, the blade, (tediously) ground from the composite part, had to be either clamped into a holder or even glued! For example, fine drilling of gearboxes.

Therefore, it is not surprising that many natural diamond tools were still used in addition to the USSR cutting material SKM, as it was known in the GDR, even for engine production.

In the late 1970s, when the Volkswagen group built the assembly lines for the four-stroke Polo engines in Salzgitter and Braunschweig, and increasingly favoured PCD, Lach Diamant was in great demand as pioneer for the development and production of PCD tools; and according to documents available to me, the sole supplier.

Rush Order for Lach Diamant

Up to the time of the Leipzig spring trade show in 1988, Lach Diamant had no business connection at all with the former GDR or any state-owned export-import collectives of the GDR – briefly called WMW Export-Import – a network of companies directly controlled by Schalck-Golodkowski.

How high the pressure on the state leadership – "We are the People" – must have been in mid 1988, that they tried to present a special treat for the people – a true highlight – at the autumn trade show in Leipzig. Four-cylinder engines for Trabant and Wartburg, made in Karl-Marx-Stadt (now Chemnitz) and Eisenach.

It is quite comprehensible that simultaneously the procurement companies became agitated in order to secure production processes. On Aug. 5, 1988, Lach Diamant received a rush order via telegram for 1,310 PCD inserts, with delivery no later than Nov. 30. This advance order also included an inquiry for approximately 4,000 additional PCD inserts with the urgent request to provide an immediate quote via telegram. It is easy to imagine that this caused quite a bustle at Lach Diamant as well.

The ordered and the additionally requested PCD inserts could easily be associated with the currently used and implemented inserts for turning and milling tasks in VW's engine production.

VW had requested Lach Diamant as sole supplier within the framework of their functional warranty to the GDR. At Lach Diamant, Günter Hobohm, Dipl. Ing., and Konrad Stibitz were immediately put in charge of the technical management of this order, which at the time was considered a major project. Gerd Gottschalk, as export manager, had the equally difficult task to finalize the contract negotiations with WMW Plauen and Berlin; this finally happened in my presence on Oct. 25, 1988, in Plauen, with two contracts resulting. In the end, the total contracted delivery was in the amount of 560,000 DM. As agreed, the first part of the order was delivered on time on Oct. 31, 1988, and the rest on Dec. 13, 1988.

"Poly" could now finally be also used in GDR state enterprises – not only as PCD tools for machining nonferrous metals, but also for furniture manufacturing, which was represented by no fewer than five furniture collectives in the GDR.

This was another area where carbide tools had been the dominating tool used for wood and composites, with very few exceptions such as diamond trial tools, delivered by tool manufacturer Ledermann & Co.

A Time of Change

The change came with the fall of the Berlin wall on Nov. 9, 1989 – up to the time of the German-German reunification, we lived in a so-called "Time of Change." It was a time of new beginnings on both sides.

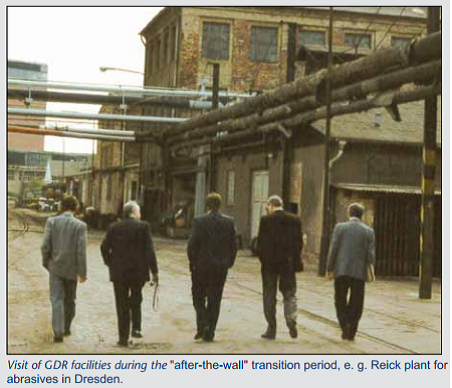

Together with Gerd Gottschalk, I visited many facilities within the GDR – many with illustrious names such as Heckert-Werke and Research Centre in Chemnitz, Robotron, a manufacturer of electronics and accounting machines, Wismut, VEB combinate "Getriebe und Kupplungen" (gears and clutches) in Magdeburg, tool manufacturer Geringswalde and abrasive producer Reick in Dresden, as well as the diamond grinding shop in Quedlinburg and many others.

After receiving requests for the finally available poly tools from various industries – by the way together with inquiries about diamond dressing rolls and grinding wheels, I decided that Lach Diamant had to establish itself as service provider and consultant in an "idle" landscape. Especially after I noticed that only two grinding machines for regrinding/sharpening of PCD tools were available for the entire GDR: An old, SWU grinding machine, modified for SKM (composite), in Jena and a second machine in the research facility of Heckert-Werke in Chemnitz. Dr. Ing. Stefan Becker, who joined us in 1990 as representative for East Germany, affirmed this approach. Within only a few months, five new sales representatives delivered knowhow and service to the "capable" companies in the East.

Unfortunately, these capable companies became less and less. Either the sudden performance pressure was too high or the necessary capital and equipment was not available or the necessary knowhow – in other words, work power – was no longer sufficiently available, due to the now actively starting migration towards the West.

Due to a lack of generated revenue, our engagement became less and less. However, the diamonds, delivered to the GDR via the VW project, were still there and should need grinding service during ongoing engine production.

New Production Site in Saxony

For this purpose, we had started the project "Lach Diamant Goes East" on Feb. 4, 1991. We had been looking for a manager for this project and found him in Dipl. Ing. Bernd Staube in December 1990. However, it must be stated, that it was difficult to arrange an interview in Hanau, since at the most only 100 telephone lines were enabled between East and West. While he had already waited several hours for a line for his call to Hanau, he then only got the response "Mr. Lach currently unavailable" after finally getting through to my secretary and was told to "try again in five minutes."

Well – we did get together after all – and he brought two new employees with him: Jörg Hänel and Dieter Miton. We had established an "autonomous" grinding service for these three in Hanau. They were trained for the establishment of a grinding and sharpening service as envisioned in the project and were prepared for opening a new production site in Saxony.

On Nov. 15, the time had come: Dipl. Ing. Bernd Straube had found a suitable location for the diamond service in Oberlichtenau near Chemnitz. Mr. Weiß, previously employed by Heckert-Werke, completed the initial team.

"All was well – but was it really well?" No, unfortunately not. The anticipated grinding orders from the new Barkas plant Chemnitz were missing – they could not come!

What had happened? Following reports which were available to me decades ago, my text and explanation should have continued as follows: The new line had been disassembled – by the Trust Agency (Treuhand) or VW (?) – and transported to China – including all poly cutting inserts.

While writing this sentence, I was beginning to doubt whether such a statement could stand up to close scrutiny today – hence the question mark. During the following, extensive research, amongst other things, I came across a report by professor Dr. Peter Kirchberg titled "The implantation of the VW engine into the automobile industry of GDR." When I talked to him in person, he vehemently excluded the possibility that these four-stroke engine times, though not up to the latest technology, would have been sold to China by VW, and certainly not by the Trust Agency, as had been assumed at the time.

The site manager of the facility in Saxony, Dipl. Ing. Bernd Straube, finally brought me onto the right track: Wikipedia – key word "VEB Barkas-Werke." It says there, among other things, in section 1.1 and 1.3 respectively, that after the line went into production, "[…] 200,000 short engines were built, and after 1988 put into Wartburg automobiles […]."

According to the above source, VW-licensed engines were built at Barkas up to 1991 for use in Wartburg and Trabant automobiles. After the fall of the Berlin wall, there was a high demand for Western cars – and the former GDR automobile production came to a standstill.

In my assessment, it took two to three years until production was resumed under the name of Volkswagen Sachsen GmbH, a full subsidiary of Volkswagen.

For Lach Diamant, trying to succeed in Saxony, the result was the same. Whether China or "Motorenwerk Barkas" – there were no orders in sight at the end of 1991.

Great grinding service facility, but what to do now? Ing. Günter Hobohm, at the time sales manager at Lach Diamant, knew what to do. In negotiations with VW Salzgitter, he received assurance that we might receive contingent of PCD cutting inserts for regrinding. We only had to pick them up and bring them back. And so it happened, that initially Mr. Straube drove in his two-stroke Wartburg to Salzgitter twice a week and kept "Lach Diamant Goes East" going.

Even the last sceptics in Hanau, if there should have been any, slowly realized what the industrious Saxonians could accomplish – at some point, with increasing personnel, they were no longer satisfied with their role as "mere service facility" and they started to also manufacture new tools. Successfully, of course.

Almost at the drop of a hat, mayor Eberhard Meyner from Lichtenau, contacted us. He was very persistent and "worked" the Lach Diamant management until they finally "gave in" and purchased a nice piece of land in his newly developed industrial area for a new plant for Lach Diamant Saxony. The move into the first hall was scheduled for Juli 1997 – two subsequent building sections were planned. Thus, a German-German success story revealed 30 years after the reunification that "it was about time that the wall came down!"

Over the last 30 years, the Lach Diamant plant in Saxony contributed to our image as pioneers and innovators in our implementation of ideas for the global automobile, wind and aircraft industries – only to name a few examples.