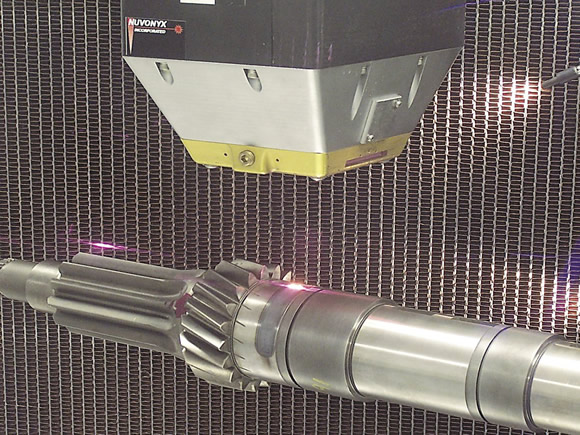

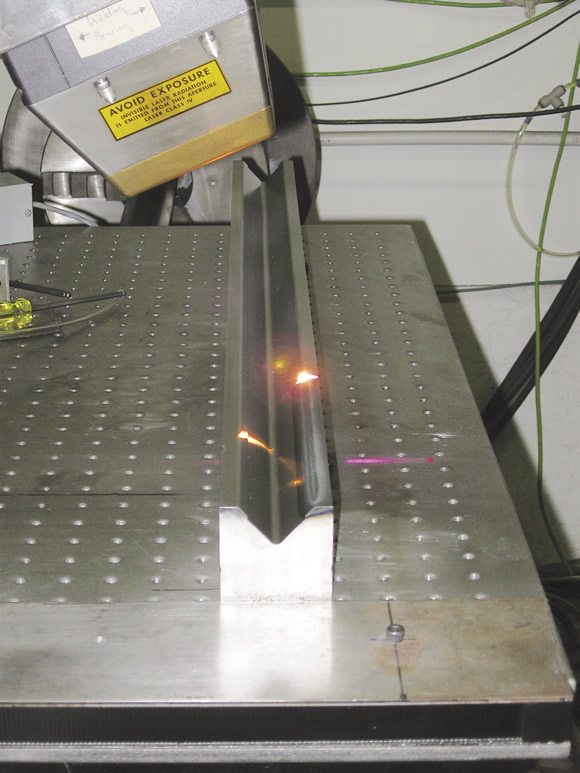

Courtesy of Coherent

A laser beam heat treats a geared shaft.

The advantages of heat treating parts with 1µm-wavelength lasers.

“I want it painted black” makes for a compelling refrain in the classic ditty by The Rolling Stones, but blackening a metal workpiece for laser surface hardening, or heat treating, creates a scenario nastier than Sir Mick’s strut.

For decades, blackening was typically required when heat treating with a CO2 laser as an alternative to induction hardening and other conventional heat-treating techniques, because the CO2 laser’s energy output at a wavelength of 10.6µm is not well absorbed by any metal. Therefore, parts to be heat treated with a CO2 laser must first be painted with an absorptive coating, such as black spray paint or black oxide, which is removed after processing.

“The paint makes smoke and it’s messy,” said Jim Cann, sales manager for Rofin-Sinar Technologies Inc., Plymouth, Mich., which makes lasers for surface hardening, as well as applications such as cutting, welding and marking. “Nobody today would use a CO2 laser for hardening.”

That’s because advancements in laser technology enable users to surface-harden parts with lasers outputting wavelengths around 1µm, which offers an approximate 45 percent absorption percentage compared to about 5 percent for CO2. These include high-power direct-diode lasers (HPDDLs), which output in the near infrared, typically at 808nm or 975nm, as well as fiber-coupled diode (about 976nm), fiber (1.03µm) and disk (1.03µm) lasers.

Because the wavelengths for these types of lasers are quite similar, they are ideally suited for heat treating, emphasized Jürgen Metzger, mechanical engineer for laser manufacturer Trumpf GmbH & Co. KG, Ditzingen, Germany. (Trumpf Inc. is based in Farmington, Conn.) “The workpiece material itself does not care whether it’s a diode, disk or fiber laser,” he said. “It only sees light with a certain wavelength.”

Also, HPDDLs provide a significant cost advantage over CO2 lasers for heat-treatment applications. Keith Parker, market development manager, direct-diode laser systems for laser manufacturer Coherent Inc., Santa Clara, Calif., pointed out that one reason is the electrical efficiency, or conversion of input electrical energy to useful light output, for a HPDDL is about three to four times higher than that of a CO2 laser. One such system is the company’s HighLight D- Series direct-diode laser.

Parker added that further savings result from reduced maintenance costs because a direct-diode laser doesn’t have the gas recharged or the mirror replaced or aligned, which is the case with CO2 lasers. Instead, only the filters for the chiller and compressed air require maintenance and the protection optic must be kept clean, Parker said. “There’s very minimal maintenance.”

Although the use of CO2 lasers for surface hardening is limited in most places, Parker noted some part manufacturers still use them because those lasers are relatively inexpensive in some local markets. However, that’s changing. “The wall plug efficiency of the CO2 laser is extremely low, typically 12 percent,” he said. “When you can implement a direct-diode laser having about 50 percent efficiency and minimal maintenance, that makes for a very compelling argument.”

In addition to CO2 lasers, Nd:YAG (neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet) lasers were often used for heat treating, but have fallen by the wayside because of their low energy efficiencies and high capital and maintenance costs, noted Gabriel Caron-Guillemette, M.Sc.A., at the University of Quebec at Rimouski (UQAR), Department of Engineering, Computer Science and Mathematics, in his paper about the use of lasers in transformation hardening.

Targeted Approach

Heat treating a part with a laser is similar to induction and flame hardening. While the laser is just another heat source, it provides more control than other sources used for hardening, according to John Haake, president and founder of Titanova Inc. “You get very repeatable results,” he said.

The St. Charles, Mo., company uses a HPDDL to heat treat parts from customers on a job shop basis. He emphasized that compared to traditional techniques, a laser’s speed and line-of-sight ability to heat specific part features means the treated area experiences minimal distortion. As a result, a treated area might only need polishing, sometimes just to remove the oxide layer, instead of grinding or hard machining. “There’s always going to be some physical movement or change in the structure, but it might fall well under the specified tolerances,” Haake said.

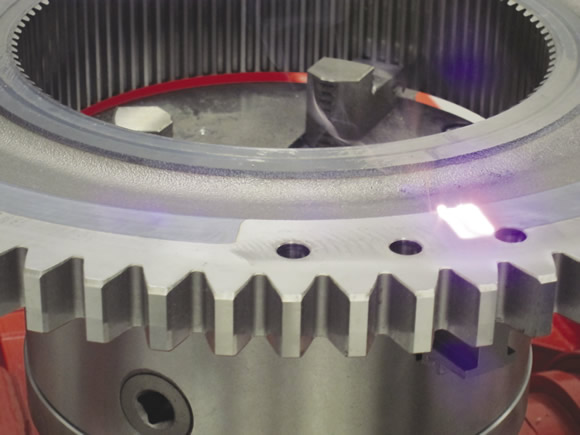

Courtesy of Coherent

A direct-diode laser from Coherent selectively heat treats the face of a gear.

Coherent’s Parker pointed out that typical heat-treatment parameters include 2kW to 8kW of power, beam size up to 36mm (with work being conducted on a 72mm beam size), process speed of 0.5 to 1.5 m/min., case hardness from 50 to 63 HRC and case depth from 0.5mm to 2mm. “For some unique applications, we have been able to achieve up to 4mm case depth,” he said.

To achieve high hardness, a narrow beam profile is moved rapidly, say, 1 m/min. or faster, over the workpiece, whereas more case depth comes from slowing the traverse speed and heating the part with a wider beam profile, such as a 12mm × 24mm rectangle, to drive the energy deeper into the part, similar to an induction process, Parker said. “You don’t want surface melting to occur.”

When looking at laser power, Joel DeKock, manager of metals applications and technology for Preco Laser Systems LLC, emphasized the importance of energy density, with the appropriate range being from 2kW/cm2 to 5kW/cm2, depending on the hardenability of the material. “If you have a small part or a local area to be treated, you could probably heat treat the whole surface just by expanding or shaping the laser beam and hitting it all at once,” he said. “But you need to have a reasonable energy density.” The Lenexa, Kan.-headquartered company builds laser based systems and performs laser heat treatment on a job shop basis. DeKock is based in Somerset, Wis.

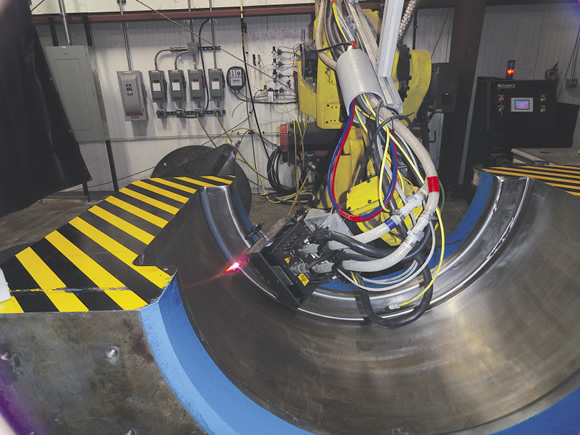

Courtesy of Titanova

Titanova heat treats the inside radius of a large hydroform die to enhance its strength.

A gear is one example of a part that’s suited to the almost surgical precision laser surface hardening offers, where specific areas are heat treated without impacting the rest of the gear. Parker noted customers often want to treat only the drive side of the gear teeth, while avoiding the other side—which doesn’t wear— and the roots of the gear teeth to avoid making them brittle and potentially causing the teeth to snap off. “With a laser, you’re able to very precisely heat treat the drive side of the tooth that is getting the high wear and keep the energy out of the root area,” he said, “so that area remains ductile.”

In general, laser surface hardening has an advantage over other processes if the part has a limited surface area that needs to be case hardened or if the part is so large that it is cost-prohibitive to heat treat via conventional means, according to Parker. “Clearly, the laser is at a disadvantage for bulk heat treating of thick parts or for applications that require large batch processing.”

Point Requirements

Despite its advantages, a laser can only effectively heat treat certain metals. A major factor is the carbon content of the workpiece material. “The higher the carbon content, the more dramatic will be the transformation process,” said Rofin-Sinar’s Cann.

Ideally, the carbon content should be above 0.35 percent, or 35 points of carbon, but steels with less carbon, such as 0.18 percent in 1018, can be laser heat treated, he noted. However, the maximum hardness and maximum case depth will be less for 1018 than for steels with more carbon (see Table 1 at right).

Table 1. Laser heat-treatable materials

Courtesy of Coherent

Maximum depth and maximum hardness for some materials do not coincide. Actual results depend on the carbon content and part geometry. Results shown are from direct-diode laser systems.

Similarly, Parker recommends laser heat treatment for materials with at least 0.30 percent carbon. “The results you achieve are directly attributable to the percentage of carbon content in that base material,” he said.

Preco’s DeKock said carbon and manganese are most important for heat treating, with other alloying elements playing a less-significant role. “In most common steels, manganese is added because that helps improve hardenability. It pushes out the time for the transformation from austenite to martensite.”

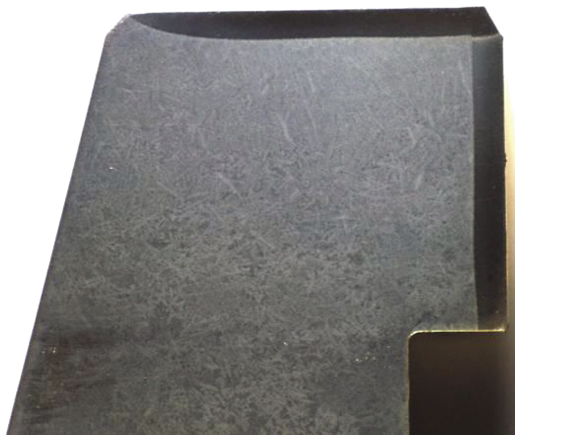

Courtesy of Trumpf

Laser heat treating offers the flexibility to harden a specific area on a part, such as a portion of a corner.

Courtesy of Rofin-Sinar Technologies

A large engine cylinder liner before and after being surface hardened with a 6kW fiber-delivered laser. The optical system had a spot size of 10mm × 30mm and used a pyrometer for surface temperature control.

DeKock added that materials with fine microstructures are easier to heat treat than ones with coarse microstructures, such as coarse pearlite. This is because a fine microstructure reduces carbon diffusion distance, or redistribution, during the short cycle time the material is heated during laser surface hardening.

In addition to low-, medium- and high-carbon steels, the types of heat-treatable materials include ferrite-hardened and low-carbon martens-itic tool steels, martensitic stainless steels and pearlitic cast iron (gray, alloyed, malleable and nodular), according to Caron-G. at the UQAR.

Nontreatable ones include workhardenable austenitic stainless steels, ferritic stainless steels, austenitic and ferritic gray iron. “Most of these steels and irons are not easily hardened by laser because of their microstructure (e.g., globular, graphite flakes) or their ability to form stable austenite at room temperature,” he said. “Laser surface hardening produces fast thermal cycle rates and high heating rates, hence it is not the best process for the treatment of steels with a coarse microstructure.”

Transformation Process

The transformation process, where the workpiece changes, is similar to conventional heat treatment when laser surface hardening. Caron-G. noted the process occurs in three stages: transformation of pearlite to austenite (pearlite dissolution), homogenization of carbon in austenite and transformation of austenite to martensite.

When applying a laser with an absorption rate of around 40 percent or more, the laser energy readily couples with the base material, enabling a fast thermal cycle, Parker explained. “You very quickly bring that base material into the austenitic phase and then just as quickly it cools,” he said, “and, on cooling, it forms a martensitic structure. That martensitic grain structure is what gives that heated area its hardness.”

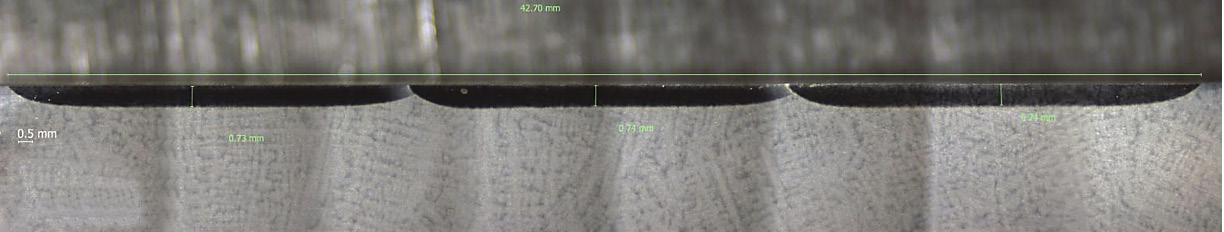

Courtesy of Preco Laser Systems

Large-area laser treatment of this steel casting uses three overlapping passes that total 42.70mm wide.

Courtesy of Titanova

Titanova heat treats the forming radius of a press brake forming die.

Unlike conventional methods, laser heat treating usually doesn’t require an oil or water bath quench to cool a part and bring about the martensite transformation. Instead, the laser process provides self-quenching. Caron-G. explained that after exposure to laser heat, the part’s untreated bulk material acts as a quenching mass, causing a cooling rate as high as 107° C/sec., allowing the hard martensite to form. To ensure self-quenching, he recommends, as a rule of thumb, a 1:10 ratio for the volume of material surrounding the hardened zone. However, a minimum of 1:6 to 1:5 can be appropriate, depending on the thermal conductivity of the material.

After nearly 6 years at Coherent, Parker said he’s only seen one part that could not be successfully heat treated without applying a quenching agent, which was a fine water mist directed on the part behind the laser beam. “The customer basically had two diametrically opposed requirements,” he said. “In that odd case, the customer needed an extremely deep case and it had to have a very high hardness, even at depth.”

He added that laser surface hardening is usually successful unless a heat-treatable part with appropriate carbon content is too thin, so it doesn’t have sufficient mass. “Typically, we don’t pursue heat-treatment applications for parts having an overall or wall thickness of less than an ¼ " or so,” Parker said.

Titanova’s Haake noted external quenchants are only required when through-heat treating thin materials because the material mass would be unable to provide self-quenching. However, such applications are rare, he added.

Beam Shaper

A laser applies different laser beam shapes to selectively and effectively heat treat a part feature, and optics shape a beam. “We typically use a line or spot,” Haake said about the shape.

Trumpf’s Metzger explained that there are two basic beam shaping techniques. One involves the use of fixed optics to create a “fingerprint” of a shape, such as a 20mm × 1mm rectangle. “It’s one fingerprint of the optics,” he said, “and the beam can only be changed by changing optical elements, like focusing elements, or by defocusing, varying the distance between the optics and the workpiece.” This is the simplest and most common type of beam shaping.

A pyrometer is used to measure the temperature in the entire laser spot, forming an average temperature, Metzger added. Therefore, the risk of melting material exists for inhomogeneous surfaces.

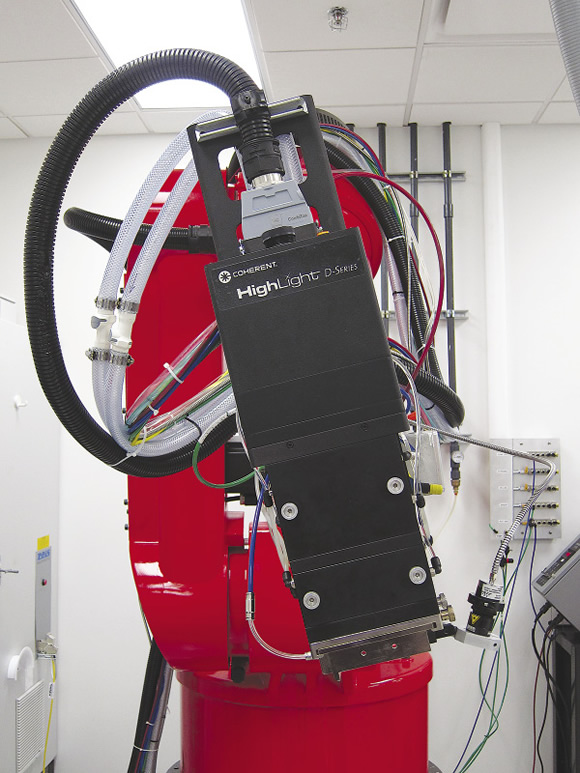

Courtesy of Coherent

Coherent’s HighLight D-Series direct-diode laser configured for heat treatment.

With a round spot, beam defocusing is a low-cost approach to static shaping, added Caron-G. By varying the distance between the focusing lens and the workpiece, the beam diameter changes and, thus, the irradiance, he explained. For the heat treating of steel, irradiance from 20MW/m² to 90MW/m² is common.

The second beam-shaping technique employs scanning optics with a moveable mirror. Metzger pointed out that a small point is moved rapidly to create a line. “We have found that 70 Hz is the best speed,” he said. The technique is a little more expensive than the fixed-optics approach but is much more precise because it uses a pyrometer to measure surface temperature as opposed to the temperature in the entire laser spot, according to Metzger.

When one shape isn’t large enough to cover the area that needs to be heat treated, the laser makes multiple tracks along the surface, and, where those tracks overlap, back tempering occurs. This can be a problem because the area where back tempering occurs has a nonuniform microstructure, a lower hardness and less compressive residual stresses, which lead to easier crack initiation at the interface between the overlap and hardened zones, noted Caron-G. He added that back tempering also reduces corrosion resistance, which depends on a high hardness and uniform microstructure. A simple technique called “dot matrix hardening” can harden large surfaces and provide a remedy to most of the technical drawbacks for multiple tracks.

Courtesy of Preco Laser Systems

Two adjacent surfaces on a P-20 tool steel part are transformation hardened to a depth of 0.045" and 0.5" in length.

Although some back temper is inevitable with multiple tracks to ensure the required area is hardened, having a larger beam reduces the overlap percentage. For example, a 6mm circle might overlap from 30 to 50 percent, whereas a 36mm beam might only overlap 10 to 17 percent, said Coherent’s Parker. “Customers who are knowledgeable about heat treating have it in their specification what percentage of the surface, such as 20 percent, is allowed to be overlapped.”

For a round part, there is always an annealed zone where the start and end of treated zones meet each other, Metzger noted. Depending on the load case, or how the workpiece is stressed, this weak point—the annealed zone—can be reduced by angling the start and end zones.

According to Parker, “a good number of shops” have implemented lasers for surface hardening and often use a Coherent HighLight D-Series laser for multiple laser processes, such as cladding, heat treating and welding. “You take the pyrometer off, put the cladding nozzle on, connect it to the power feeder and now you can do metal deposition/overlay,” he said. “In some cases, the same tool can also be used for conduction-mode welding.”

Metzger stressed that when a parts manufacturer integrates a laser into its production environment, safety and the need for a light-tight enclosure are paramount so workers don’t damage their eyes by viewing the laser light.

Depending on the part size and level of automation, the cost of a laser surface-hardening system varies as much as The Glimmer Twins’ songwriting output. “It could be from $100,000 to $1.5 million,” said Titanova’s Haake. “If it’s a real tiny part, you could do it for maybe $100,000, but figure half a million. And you have to have the know-how.”

Some shops reduce the automation cost by creatively integrating laser technology. Parker noted one customer removed the mill from a Bridgeport mill, replaced it with a laser and controlled the laser’s motion with the CNC.

Overall, a laser applied for heat treating provides a highly controllable, precise and repeatable process. “It’s more of a finesse method,” said Rofin-Sinar’s Cann. “It’s kind of a scalpel versus an axe method of hardening.” CTE

Contributors

Coherent Inc.

(800) 227-8840

www.coherent.com

Preco Laser Systems LLC

(800) 966-4686

www.precoinc.com

Rofin-Sinar Technologies Inc.

(734) 455-5400

www.rofin-inc.com

Titanova Inc.

(636) 487-0070

www.titanovalaser.com

Trumpf Inc.

(860) 255-6000

www.us.trumpf.com

University of Quebec at Rimouski

(418) 724-1610

www.uqar.ca/genie

Related Glossary Terms

- austenite

austenite

Solid solution of one or more elements in face-centered cubic iron. Unless otherwise designated (such as nickel austenite), the solute is generally assumed to be carbon. Austenite can dissolve up to 2 percent carbon. Austenite is relatively soft, ductile and nonmagnetic.

- black oxide

black oxide

Black finish on a metal produced by immersing it in hot oxidizing salts or salt solutions.

- computer numerical control ( CNC)

computer numerical control ( CNC)

Microprocessor-based controller dedicated to a machine tool that permits the creation or modification of parts. Programmed numerical control activates the machine’s servos and spindle drives and controls the various machining operations. See DNC, direct numerical control; NC, numerical control.

- corrosion resistance

corrosion resistance

Ability of an alloy or material to withstand rust and corrosion. These are properties fostered by nickel and chromium in alloys such as stainless steel.

- diffusion

diffusion

1. Spreading of a constituent in a gas, liquid or solid, tending to make the composition of all parts uniform. 2. Spontaneous movement of atoms or molecules to new sites within a material.

- flame hardening

flame hardening

Hardening process in which an intense flame is applied to the surfaces of hardenable ferrous alloys, heating the surface layers above the upper transformation temperature, whereupon the workpiece is immediately quenched.

- grinding

grinding

Machining operation in which material is removed from the workpiece by a powered abrasive wheel, stone, belt, paste, sheet, compound, slurry, etc. Takes various forms: surface grinding (creates flat and/or squared surfaces); cylindrical grinding (for external cylindrical and tapered shapes, fillets, undercuts, etc.); centerless grinding; chamfering; thread and form grinding; tool and cutter grinding; offhand grinding; lapping and polishing (grinding with extremely fine grits to create ultrasmooth surfaces); honing; and disc grinding.

- hardenability

hardenability

Relative ability of a ferrous alloy to form martensite when quenched from a temperature above the upper critical temperature. Hardenability is commonly measured as the distance below a quenched surface at which the metal exhibits a specific hardness (50 HRC, for example) or a specific percentage of martensite in the microstructure.

- hardening

hardening

Process of increasing the surface hardness of a part. It is accomplished by heating a piece of steel to a temperature within or above its critical range and then cooling (or quenching) it rapidly. In any heat-treatment operation, the rate of heating is important. Heat flows from the exterior to the interior of steel at a definite rate. If the steel is heated too quickly, the outside becomes hotter than the inside and the desired uniform structure cannot be obtained. If a piece is irregular in shape, a slow heating rate is essential to prevent warping and cracking. The heavier the section, the longer the heating time must be to achieve uniform results. Even after the correct temperature has been reached, the piece should be held at the temperature for a sufficient period of time to permit its thickest section to attain a uniform temperature. See workhardening.

- hardness

hardness

Hardness is a measure of the resistance of a material to surface indentation or abrasion. There is no absolute scale for hardness. In order to express hardness quantitatively, each type of test has its own scale, which defines hardness. Indentation hardness obtained through static methods is measured by Brinell, Rockwell, Vickers and Knoop tests. Hardness without indentation is measured by a dynamic method, known as the Scleroscope test.

- heat-treating

heat-treating

Process that combines controlled heating and cooling of metals or alloys in their solid state to derive desired properties. Heat-treatment can be applied to a variety of commercially used metals, including iron, steel, aluminum and copper.

- induction hardening

induction hardening

Surface-hardening process in which only the surface layer of a suitable ferrous workpiece is heated by electromagnetic induction to above the upper critical temperature and immediately quenched.

- martensite

martensite

Formed during rapid cooling of austenite at the temperature rate higher than 500º F (260º C) per second. Such rapid cooling causes restructuring of crystalline lattice of gamma iron into crystalline lattice of alpha iron in which carbon is fully dissolved. Because only 0.04 percent carbon can be dissolved in alpha iron, the excessive amount of carbon transforms into supersaturated solution of carbon in alpha iron. This type of solution is called martensite, which is characterized by an angular needlelike brittle structure and high hardness (greater than 60 HRC).

- microstructure

microstructure

Structure of a metal as revealed by microscopic examination of the etched surface of a polished specimen.

- milling machine ( mill)

milling machine ( mill)

Runs endmills and arbor-mounted milling cutters. Features include a head with a spindle that drives the cutters; a column, knee and table that provide motion in the three Cartesian axes; and a base that supports the components and houses the cutting-fluid pump and reservoir. The work is mounted on the table and fed into the rotating cutter or endmill to accomplish the milling steps; vertical milling machines also feed endmills into the work by means of a spindle-mounted quill. Models range from small manual machines to big bed-type and duplex mills. All take one of three basic forms: vertical, horizontal or convertible horizontal/vertical. Vertical machines may be knee-type (the table is mounted on a knee that can be elevated) or bed-type (the table is securely supported and only moves horizontally). In general, horizontal machines are bigger and more powerful, while vertical machines are lighter but more versatile and easier to set up and operate.

- pearlite

pearlite

Lamellar aggregate of ferrite and cementite in slowly cooled iron-carbon alloys occurring normally as a principle constituent of steel and cast iron. Fully annealed steel containing 0.85 percent carbon consists entirely of pearlite.

- polishing

polishing

Abrasive process that improves surface finish and blends contours. Abrasive particles attached to a flexible backing abrade the workpiece.

- quenching

quenching

Rapid cooling of the workpiece with an air, gas, liquid or solid medium. When applicable, more specific terms should be used to identify the quenching medium, the process and the cooling rate.

- shaping

shaping

Using a shaper primarily to produce flat surfaces in horizontal, vertical or angular planes. It can also include the machining of curved surfaces, helixes, serrations and special work involving odd and irregular shapes. Often used for prototype or short-run manufacturing to eliminate the need for expensive special tooling or processes.

- slotting machine ( shaper)

slotting machine ( shaper)

Vertical or horizontal machine that accommodates single-point, reciprocating cutting tools to shape or slot a workpiece. Normally used for special (unusual/intricate shapes), low-volume runs typically performed by broaching or milling machines. See broaching machine; mill, milling machine.

- stainless steels

stainless steels

Stainless steels possess high strength, heat resistance, excellent workability and erosion resistance. Four general classes have been developed to cover a range of mechanical and physical properties for particular applications. The four classes are: the austenitic types of the chromium-nickel-manganese 200 series and the chromium-nickel 300 series; the martensitic types of the chromium, hardenable 400 series; the chromium, nonhardenable 400-series ferritic types; and the precipitation-hardening type of chromium-nickel alloys with additional elements that are hardenable by solution treating and aging.

- tempering

tempering

1. In heat-treatment, reheating hardened steel or hardened cast iron to a given temperature below the eutectoid temperature to decrease hardness and increase toughness. The process also is sometimes applied to normalized steel. 2. In nonferrous alloys and in some ferrous alloys (steels that cannot be hardened by heat-treatment), the hardness and strength produced by mechanical or thermal treatment, or both, and characterized by a certain structure, mechanical properties or reduction in area during cold working.

- tool steels

tool steels

Group of alloy steels which, after proper heat treatment, provide the combination of properties required for cutting tool and die applications. The American Iron and Steel Institute divides tool steels into six major categories: water hardening, shock resisting, cold work, hot work, special purpose and high speed.