Hybrid machine tools for moldmakers

Hybrid machine tools for moldmakers

The advantages of combining additive manufacturing with finish-machining processes in a single setup are plentiful, from shorter cycle times to the ability to create complex, unlikely geometries. Because of the specific needs of their industry, moldmakers might feel left out. However, a few machine builders are filling this niche-within-a-niche.

The advantages of combining additive manufacturing with finish-machining processes in a single setup are plentiful, from shorter cycle times to the ability to create complex, unlikely geometries. The most commonly available hybrid machines include machining centers with laser-metal-deposition (LMD) nozzles for 3D printing.

Because of the specific needs of their industry, moldmakers might feel left out. However, a few machine builders are filling this niche-within-a-niche.

'I Am Your Density'

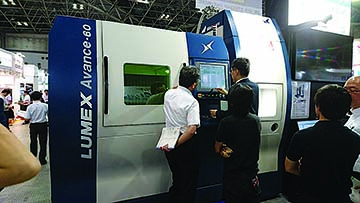

"When it comes to choosing a hybrid machine for moldmaking, there are only two systems I'm aware of that can do the job," said William Gillcrist, national product manager – machining/additive divisions for MC Machinery Systems Inc., "and that's Lumex and [the OPM250L system by] Sodick." The Wood Dale, Ill.-based Mitsubishi subsidiary is the U.S. distributor for Lumex, a line of hybrid machine tools born of a collaboration between Japanese machine tool builders Mitsubishi Corp. and Matsuura Machinery Corp.

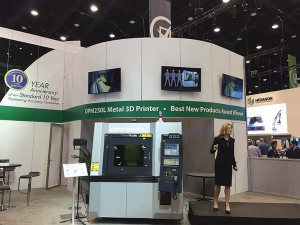

Sodick's OPM250L hybrid machine blends CNC milling with powder-bed fusion

for moldmaking applications. Image courtesy of Sodick.

The reason for the low level of competition has a lot to do with technological challenges inherent to the process, according to Evan Syverson, marketing manager for Sodick Inc., Schaumburg, Ill.

"In order to print something that is adequate for moldmaking, you need to use direct metal laser sintering," he explained, adding that DMLS provides a suitable density for molds.

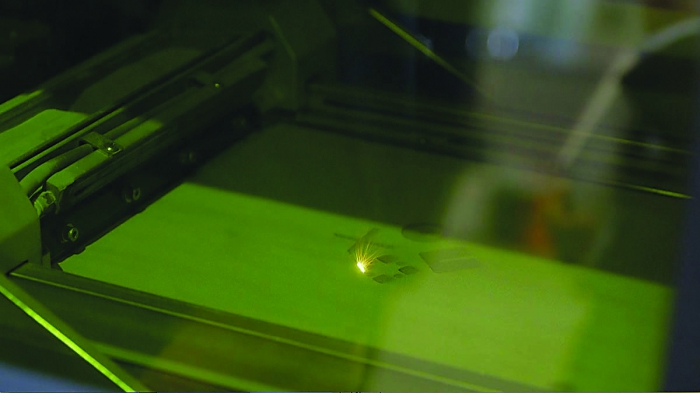

Also known as powder-bed fusion, the process involves firing a fiber laser into a bed of powder metal (PM), which melts or welds the material together to create the part structure. While LMD is by far the most common method in hybrid machines, that process—in which PM is essentially sprayed and then melted onto the work surface—creates structures that are too porous for molds, Syverson noted.

"Those types of machines have considerable utility in repair and fabrication work," Syverson said, "but with a powder bed, the material density endemic to the process lends itself more closely to moldmaking."

Density is critical, he explained, because even small deviations can dramatically reduce the lifespan of a mold. For example, a 0.1 percent difference in density can yield a 50 percent reduction in tool life. Sodick's OPM250L offers a reliable part density of 99.99 percent, while other 3D printers may be limited to 99.7 percent density or lower, according to Syverson.

The combination of additive and subtractive manufacturing can yield complex, intricate mold geometries

with extremely fine surface finishes, without involving an EDM. Image courtes of MC Machinery Systems.

However, milling a workpiece surrounded by PM in the bed poses unique challenges, which may explain why the technology is not more widespread. For example, the presence of PM risks reducing tool life by increasing friction and adding to the amount of material the tool must work through. Plus, conventional oil-air mist lubrication cannot be applied because of safety issues related to the exposure of a flammable material to laser radiation.

MC Machinery's Gillcrist has seen demonstrations of several 5-axis hybrid machines with spray-deposition capability, but, he said, when switching between additive and conventional machining, the coolant must be drained from the work area so it does not interfere with the powder-deposition process. This drawback is not present with DMLS systems.

"Lumex is a dry system," he said, "so, without coolant to worry about, the part can move back and forth without difficulty or interruption."

Printing in Process

DMLS hybrids offer a number of distinct advantages, from shortening lead times to enhancing design flexibility to—well, achieving the previously impossible. Sodick's Syverson explained that there is not yet a 3D printer on the market that can achieve the necessary surface resolution without finish machining. Using a hybrid machine rather than moving to another machine for finishing eliminates the need for multiple setups, and allowing the spindle to finish a part as it is being printed cuts cycle time.

Effectively alone in their class, Matsuura's Lumex Avance-60 and Sodick's OPM250L hybrid machines cause a stir at trade shows. Images courtesy of Matsuura Machinery (left) and Sodick.

"Besides the obvious," he said, "parts can be designed such that various offsets can be created, then milled in process, which increases accuracy from ±0.010" to ±0.001"—a huge leap."

Matsuura's Lumex machines boast similar selling points. Prototypes can often be completed in a single untended machining cycle, according to Gillcrist, and the cycle times in the molding process can be further reduced by building internal cooling channels into a mold. Perhaps most surprisingly, this hybrid technology has allowed MC Machinery to almost—not entirely—eliminate the need for a sinker EDM on the shop floor.

"Every 10 layers, the laser stops and the spindle moves over to do some rough semifinishing of the top 10 layers, followed by a finish path on the previous 10 layers," he explained, meaning the spindle is able to work in areas of the workpiece that might become unreachable once the part is complete. "That means we can generate some very deep structures or ribs that were previously only achievable via EDM."

Capital City

For all their advantages, why aren't these machines synonymous with moldmaking? It all boils down to money. Many moldmaking shops are small, and a capital investment of $650,000 to $1 million for a DMLS hybrid machine is considerable.

"The quickest way to get a return on investment is when shops are handling the designing and casting in addition to the moldmaking processes," Gillcrist said. "If a shop is contracting out some aspects of the work, it can be difficult to justify the investment."

However, there is now another company vying for a share of the moldmaking market. Hybrid Manufacturing Technologies is giving additive capabilities to virtually any existing CNC machining center.

Founded in 2012, the McKinney, Texas, company manufactures the AMBIT series of patented deposition heads and docking systems. Because AMBIT is based on LMD, you won't see a user printing a mold from the ground up. Still, Hybrid's modularized approach to in-process metal cladding has garnered a lot of attention. The company won the inaugural International Additive Manufacturing Award, valued at $100,000, from AMT – The Association For Manufacturing Technology.

Hybrid Manufacturing Technologies' AMBIT system can be fitted to a standard CNC spindle,

making switching between additive and subtractive machining processes no different than any other tool change.

Image courtesy of Hybrid Manufacturing Technologies.

"There are multiple opportunities for this technology within moldmaking," said Hybrid CEO Jason Jones. These include restoring a mold to its original dimensions and modifying an out-of-tolerance mold. "Another, which has the biggest impact, is to enhance a mold so that it's better than the original mold."

Restoring old molds or modifying new ones can provide substantial cost savings, he continued, because out-of-spec molds don't necessarily have to be scrapped and replaced. Such "enhancements"—adding a wear-resistant coating to critical surfaces of a humble tool steel mold, for instance—is an affordable way to significantly lengthen mold life.

"Most people don't think of plastic or glass as being particularly hard or abrasive, especially compared to steel," Jones said, "but when you're injection molding, the molten material wears away the mold as it flows, to the point that the mold has to either be thrown out or refurbished. Cladding the surfaces most prone to wear means you are getting performance that's comparable [to a mold made of a much harder and more expensive material]."

In addition, traditional moldmaking involves roughing, heat treating and finish machining, rendering alterations to the finished mold difficult and costly, he said. AMBIT heads allow machinists to weld new material to the mold and impart the desired finish in the same setup, at a much lower cost than making an entirely new mold.

While hybrid options for moldmakers are currently slim, the possibilities offered by the technology are myriad. Whether printing from powder or adding to existing architecture, one thing is clear: The future of moldmaking has already begun.