Keep The Machine Doors Closed

Keep The Machine Doors Closed

The ultimate goal of tool-monitoring technologies is to help shops keep their machine tool doors closed longer — because open doors let the money out.

Everyone agrees that the job market is crazy. Keeping skilled people in front of machines is the biggest challenge faced by modern machine shops. As a result, shops are increasingly turning to automation to offset the demand for skilled craftsmen.

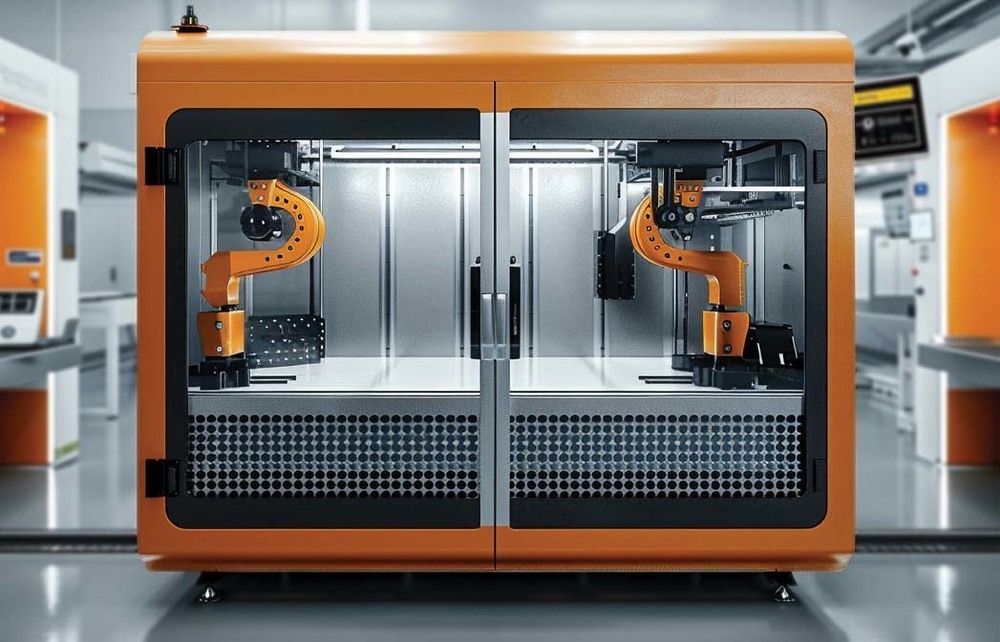

Automation can be simple like a bar feeder on a lathe or complex like a fully integrated robot. In other cases, it might be a high-capacity magazine coupled to a horizontal machining center with multiple pallets. In all cases the goal is to keep the machine producing parts with minimal human intervention. Or as we say where I work, "keep the doors closed longer." Because open machine tool doors let the money out.

When a machine is running unattended a broken or damaged cutting tool can be catastrophic. So, one of the key components to successfully automating a machining operation is implementing tool management. A world class tool management regime not only safeguards the process from broken tools, it also recognizes worn tools and has the ability substitute tools when necessary.

Tool monitoring can take a few forms. Some methods of monitoring are straightforward and cost-effective while others can be very complex and expensive.

For a shop on a budget the simplest way to protect an automated process from broken tools is to use tool life management software that is included in the machine's control. Modern CNC controls come with onboard tool life management that allows the user to monitor and limit tool cutting times. Users can measure total cut time or, more commonly, the number of parts, and when a limit is reached the machine ceases to use the old tool. Controls also allow the user to designate alternates to be used so that machining operations continue uninterrupted after a tool has reached end of life.

At a previous employer we had machining centers combined in a cell with robotic loaders. Obviously with robotic loading there should be very little human intervention. In this case things did not go well because we had tooling issues, setup issues and quality problems. The machines were set up with one roughing tool and one finish tool and they were only good for 100 parts before they needed to be changed.

Because of the numerous issues. tool changes could cost us four to eight hours of production. Our first step in solving the issues was to load the machine up with eight roughing tools and eight finish tools and utilize the onboard tool management software. Once we reached 100 parts the machine would cease using the current tools and start to use the next set of tools without interruption. We were not only more productive, we bought ourselves time to work on the other problems.

Tool management software is effective, but it will not detect broken tools. In the scenario above there was almost zero chance of breaking a tool so we only used the onboard software. In other cases where there is high risk of tools breaking it is necessary to monitor tools for breakage.

There are a few types of contact devices available for broken tool detection. Whisker sensors are a simple option. These devices have a small wire that is rotated into the tool and the position indicates if the tool is present. Obviously if the tool is broken, the rotating wire travels too far and the machine is signaled. These can be used outside of the machining envelope, so they do not interrupt production and they are often found on the tool changer.

Whisker sensors can easily miss a broken tool if the break is below the point where the whisker sensor contacts the tool. When processes are less stable, and tool breakage is more likely, a different monitoring tool may be needed.

Tool probes or tool setters are the next option. Although they were developed for onboard tool measurement, they are also ideal for monitoring cutting tool condition. These devices are typically found inside the machining envelope and used for measuring and recording tool lengths. Cutting tools are fed into the setter in a controlled manner and the setter triggers the machine to stop. Once stopped the machine will read and record the position of the tool so it can be used later.

Measuring and monitoring the tool length is the best way to detect small fractures that can cause problems. Chipped drill points, broken flutes and similar fractures that are missed with whisker sensors can be detected with a contact tool. When the tools are broken, length and diameter measurements change. Measurements can be compared inside the program and deviations can trigger the control to take corrective actions.

Laser tool setters are a more advanced, non-contact option that work like the contact type tool setters. Laser setters measure length and diameter and provide the same options for triggering the machine as the contact type. They are typically faster and can be used while the machine spindle is rotating, which can offer some moderate time savings. They are most effective when delicate tools are being used and there is concern that contact with a tool setter could damage the cutting tool. Laser setters also offer measurement options that contact type setters do not, like the ability to measure the corner radius of a cutting tool.

For the ultimate in tool monitoring there are electronic monitoring devices that can be connected to a machine tool that are capable of reading the machine tool condition and triggering corrective actions during the machining process. These electronic devices receive input from sensors attached to the machine, interpret the data and signal the machine tool control to take action. Electronic monitoring can be used alone but is almost always used in conjunction with tool setters.

Unlike the tool setters, electronic monitoring can sense a change in spindle load indicating a dull or broken tool while the machine is in the cut. It can also sense chatter and change cutting speeds on the fly. In the most advanced systems, electronic monitoring can sense increases in force on the machine axes indicating problems with the cutting tool or the condition of the machine. Electronic monitoring is often an integral part of world class total productive maintenance programs (aka TPM) because it can provide a large amount of data on the machine tool condition. Obviously, they are also the costliest systems and are usually reserved for very high volume machining operations with very expensive workpieces.

As the number of skilled employees continues to decrease and the need for autonomous machining increases, shops of all sizes are going to work to reduce the need for human intervention. Doing so necessitates that shops introduce some method of monitoring the condition of cutting tools to reduce the risks associated with damaged tools and help keep the doors closed longer. Tool monitoring is a foundational part of automated machining processes and should not be overlooked.