What to do with workpiece rpm when burn occurs

What to do with workpiece rpm when burn occurs

The Grinding Doc finds a need for speed in cylindrical plunge grinding.

The Need for Speed

Dear Doc: I cylindrical plunge-grind carbide with diamond wheels and steel with CBN and Al2O3 wheels. There's disagreement in the shop about what to do with the workpiece rpm when burn occurs. Some say speed it up. Some say slow it down. Which is correct?

The Doc replies: The typical philosophy for many grinders is "When something bad happens, slow things down." When it comes to burn in cylindrical plunge grinding, this is absolutely wrong. Let's look at the general trends.

Increasing the workpiece rpm leads to: lower workpiece temperature and lower risk of burning or cracking (almost always); more wheel wear (usually); rougher (higher Ra) surface finish (almost always, but often the change isn't that large, and spark-out frequently negates it anyway); and increased risk of chatter (usually).

Conversely, decreasing the workpiece rpm leads to: higher workpiece temperature and greater risk of burning or cracking (almost always); less wheel wear (usually); smoother (lower Ra) surface finish (almost always, but often the improvement isn't that large, and spark-out frequently negates it anyway); and decreased risk of chatter (usually).

Keep in mind that all these trends are for cylindrical plunge grinding. If you're doing cylindrical traverse, then everything I've written here is wrong. To further complicate things, if you're doing cylindrical plunge with oscillation, all these trends apply if the workpiece always stays on the wheel — provided that you don't have significant wheel wear, such as in grinding PCD or PCBN with diamond or grinding high-vanadium HSS with Al2O3. If the workpiece leaves the wheel or if there's huge wheel wear, then the trends may apply. If you have a swivel on your wheelhead — for example, the typical 30° swivel — then all these trends apply on both the OD and the shoulder. Finally, they all apply for both cylindrical OD plunge and cylindrical ID plunge.

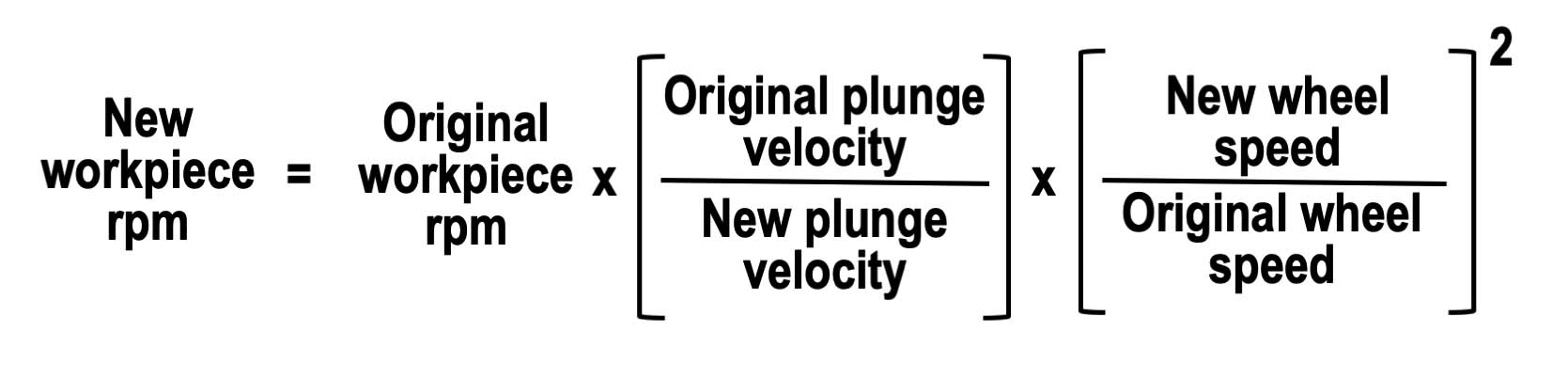

A common situation with my customers who grind carbide with a diamond wheel is as follows: They want to increase feed rates, but when they do, they get too much wheel wear or form breakdown. This is caused by the increase in aggressiveness — or if you prefer, chip thickness — when they increase the plunge velocity. The figure shows a quick, easy formula to keep aggressiveness constant while increasing the feed rate.

Let's say you're cylindrical plunge grinding at 60 rpm for the workpiece, 1,800 rpm for the wheel and a 1 mm/min. (0.04 ipm) feed rate. You want to increase the feed rate to 1.5 mm/min. (0.06 ipm). If you increase only the feed rate, the diamonds will dig in deeper, causing more wheel wear. Do this instead: Keep the wheel speed the same, but decrease your workpiece speed to 40 rpm (60 × 1 ÷ 1.5 × 1,800 ÷ 1,800 = 40). By doing this, your aggressiveness and wheel wear will stay the same.

If you want to get fancy, increase the wheel speed to 2,100 rpm and decrease your workpiece to 54.4 rpm [60 × 1 ÷ 1.5 × (2,100 ÷ 1,800)2 = 54.4]. Why increase the wheel speed? With the faster plunge velocity, you can keep the same aggressiveness by either decreasing the workpiece rpm or increasing the wheel rpm. For a fixed aggressiveness, a slower workpiece rpm means higher grinding temperatures. A faster wheel speed doesn't. What's more, the square term means that wheel speed has a bigger effect than workpiece rpm.

Play around with it and see what happens. The beauty of this equation is that you can use any units you want — rpm, sfm, meters per second, furlongs per fortnight — as long as you're consistent.