Using CMMS to test component quality and improve machine design

Using CMMS to test component quality and improve machine design

Modern maintenance professionals understand the basic importance of their computerized maintenance management systems (CMMS). After all, it is an essential tool when it comes to scheduling and tracking maintenance work. Yet, a CMMS has so much more potential as a value provider to the business. To untap its true power, let us first discuss the holistic approach to maintenance.

Modern maintenance professionals understand the basic importance of their computerized maintenance management systems (CMMS). After all, it is an essential tool when it comes to scheduling and tracking maintenance work. Yet, a CMMS has so much more potential as a value provider to the business. To untap its true power, let us first discuss the holistic approach to maintenance.

Many factories mistakenly focus first on reducing overall maintenance cost. They focus on the maintenance budget and how it can be reduced. They may view the maintenance expense as non-value added (i.e. not increasing profits) and therefore attempt to decrease it.

Rather than focus solely on maintenance spend, a recommended approach is to emphasize the goal of the maintenance team. The goal is to keep equipment running and in prime condition. Therefore, maintenance should be primarily judged on equipment uptime, with overall spend a secondary measure. This mentality helps a factory understand the "true cost" of its maintenance department.

Ultimately, the goal of a manufacturing operation is to make quality product – at or below target cost. Maintenance should fit into this goal by helping to keep the equipment running smoothly, which will reduce the number of defects and minimize the occurrence of expensive downtimes.

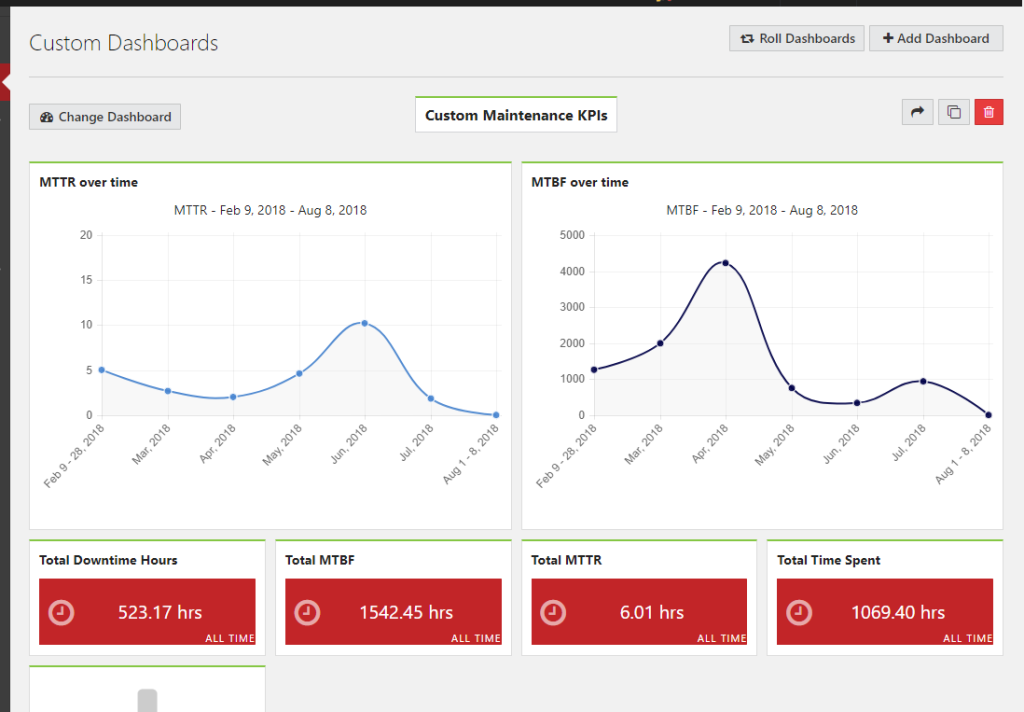

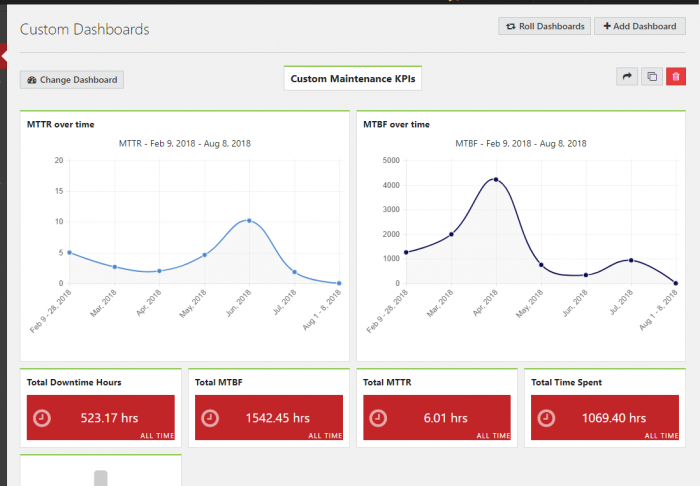

This mindset can be extended into detail using the factory CMMS. There is a plethora of data available in a computerized maintenance system that can be leveraged to improve the factory. Some examples will be discussed below.

Replacement Part Reliability

One way to utilize the data already stored in the CMMS is in replacement part reliability. Using this platform to its fullest extent, tracking different part data becomes possible. This data could include:

- time of service

- downtime for replacement

- failure mechanism

This continues the theme of "holistic maintenance." Every one of these factors can be considered in part purchasing. Purchasers may be merely working from part cost. This would be akin to only tracking maintenance department spend. There are many other factors to consider for optimizing the operation.

For example, a reliability centered maintenance (RCM) approach to failure modes may find that the part in question needs more robustness. Perhaps the part composition is the not the optimal material for the process. Rather than saving money on the part, replacing with a more durable part will save money for the entire process.

We saw this example at our client's facilities. They were "saving" pennies on replacement gaskets, filters and bearings, while losing hundreds of dollars in downtime replacing them. There was a disconnect between the parts ordering and the operations and engineering team.

In one instance, they noticed how they are repeatedly losing pumps on a specific line due to bearing failure. After some basic analysis, the conclusion was that the bearings they were using were not rated for the temperature during part of the process. The process had been changed at some prior time and the equipment had not all been updated along with the change. They simply upgraded the bearings and the problem was solved.

However, it is not always easy to make this connection. A modern CMMS platform can certainly help. Purchasers should be trained to periodically question the parts that they are ordering. There should be regular dialogue between the operations, engineering and the purchasing team.

If you are unsure of how to start this analysis, a simple method is an A/B test. Conduct it on two similar machines or the same machine at different times. Test the replacement parts using the CMMS to track service time and failure metrics like MTBF.

Indirect Costs

There are many more costs to be studied when examining the overall cost of a component. You can also consider:

- Energy consumption

- Temperature

- Speed (rpm)

- Transmitted Power (kW)

- Transmittable Torque (Nm)

- Generated noise (dB)

- Machine guarding

However, you have to keep in mind that properly tracking some of the things mentioned on the list above means investing in a variety of condition monitoring tools and equipment. Some maintenance systems can save the data for you, but they need something or someone to feed them that data.

Machine Design

As part of a robust design project (either new design or a retrofit), maintenance of the machine should be a key consideration. In the end, you cannot use the machine if it is not functioning properly.

This can be illustrated when examining an underperforming machine. Experienced manufacturing individuals have likely seen this on their floor. In some instances, the machine reliability is poor enough that a redesign is needed.

In such cases, the data stored in a CMMS can be extremely helpful. What is the failure mode, and what can be improved? The factory engineering team can work with the OEM (or another vendor) and use the CMMS data to design a solution to the problems they are frequently facing.

In certain cases, a capital expenditure for new equipment is necessary. To justify this expense to management, clear data is absolutely necessary. What is the current downtime cost, and how will the new equipment offset this cost? Management will not approve the expense if they do not see the value backed by good data to validate the assumptions.

In a modern factory, management requires hard data to justify changes to the operation. The good news is that much of this data is available to CMMS users. Operations, maintenance, engineering and purchasing should all be leveraging the stored data to help meet their respective goals.

The overall goal of the operation should be the primary focus. A holistic approach to maintenance may reveal that the factory is not making the best decisions in day-to-day operations. Simply focusing on costs can often result in missing hidden or secondary factors which, in many cases, are more valuable to the operation. Using a modern CMMS, the factory can find many valuable insights to optimize their processes and ultimately increase profits.