Four-fluted end mill extends tool life

Four-fluted end mill extends tool life

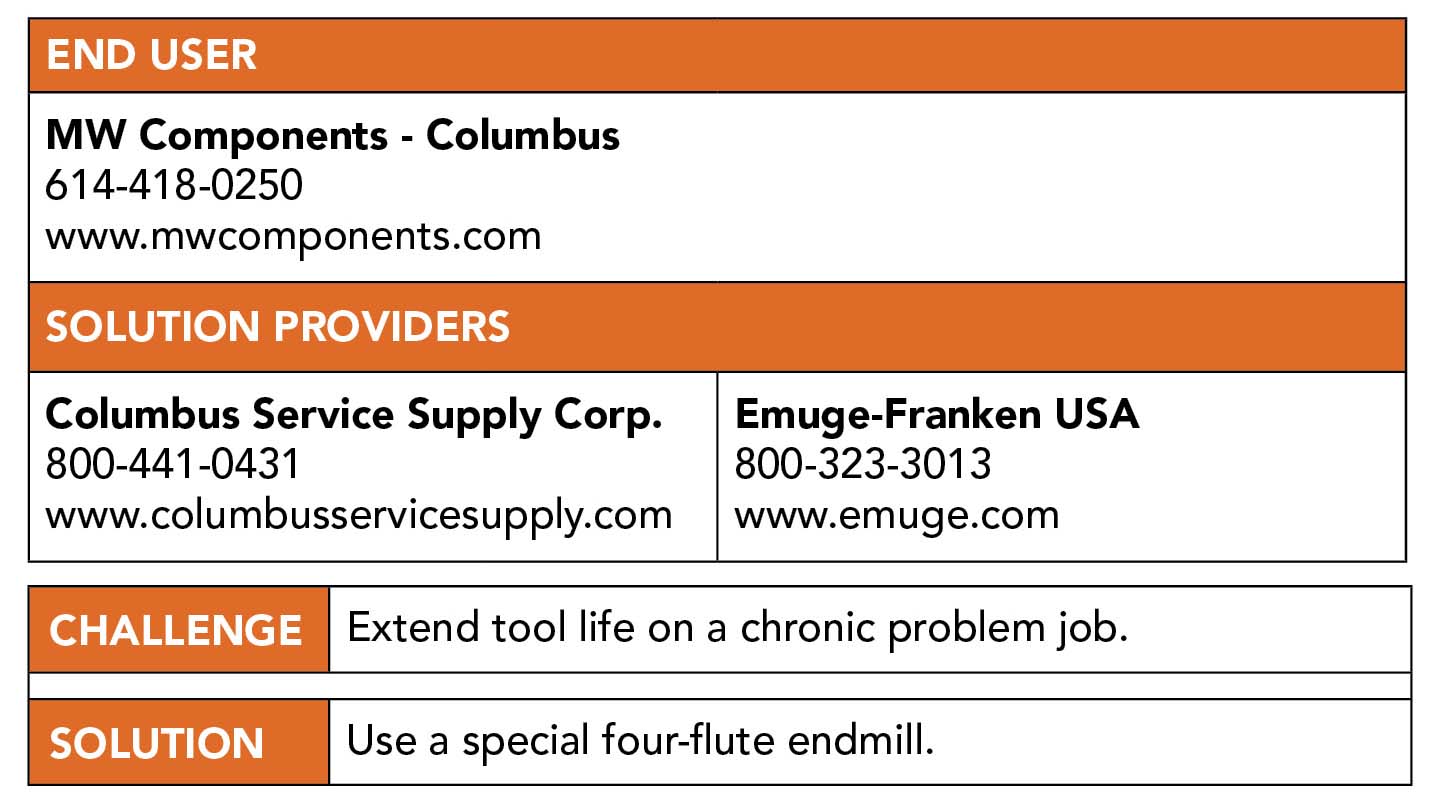

With an eye toward continuous improvement, MW Components - Columbus likes to test cutting tools and solve issues on problem jobs.

Like many in his position, Tommy Coulter likes to put cutting tools to the test from time to time. A CNC programmer and tool and die maker for MW Components - Columbus in Columbus, Ohio, he calls this continuous improvement exercise "drag racing," a process that involves bringing in multiple suppliers to see who has the best cutting tool to solve a particular machining problem.

He undertook such an exercise late last summer and reported an "award-winning" experience. With assistance from his cutting tool distributor and Emuge-Franken USA in West Boylston, Massachusetts, the shop was able to increase tool life 10 times compared with the endmill he'd been using for several years, saving the company more than $31,000 on one job alone.

"I expected some amount of improvement in tool wear," Coulter said. "But to be honest, we were all a little shocked at the results."

Formerly known as Capital Spring Co., MW Components - Columbus has produced springs, wire forms and small metal stampings since 1945. It uses CNC coiling technology and high-performance machine tools and stamping equipment to improve throughput, increase repeatability and reduce costs for customers.

With an eye toward continuous improvement, Tommy Coulter, CNC programmer and tool and die maker at MW Components - Columbus, likes to test cutting tools from time to time. Image courtesy of MW Components - Columbus

The company hired Coulter six years ago, and one of his more immediate tasks at that time was tooling up for a family of high-volume specialty automotive springs. So he went drag racing. The original project included purchasing an Okuma four-axis MB-4000H horizontal machining center, along with the tombstones, fixtures and toolholders needed to process workpieces in batches of 14 to 20 per tombstone face, depending on the part number.

The application involved milling a feature on the end of a 9.525 mm-dia. (0.375") piece of 4140 steel with a hardness from 28 to 32 HRC, one that had been turned on a screw machine and then bent into a specific shape.

"And that was the root of the problem," Coulter said. "The part and cutting tool alike have to stick out a long way in order to clear one of the bends, and there's simply no way to stabilize it. Picture a pencil that's standing straight up and then trying to machine it with a tool 3" (76.2 mm) long. There are some serious flex issues going on there."

Despite these challenges, he was able to develop a sufficiently stable process, so the company has been making the part for nearly five years. The only problem was the need to stop the machine every 300 parts to change endmills, a chronic headache that he'd tried repeatedly — and unsuccessfully — to eliminate.

In the spirit of drag racing, Coulter reached out to Jason Frye, area sales representative for cutting tool and industrial equipment supplier Columbus Service Supply Corp. in Worthington, Ohio. Frye took one look at the application and reached out to Emuge-Franken.

"Emuge asked me what I was looking for in a cutting tool, and I explained that side loading was a huge issue," Coulter said. "I was using a trochoidal milling technique with a high-quality, extended-length cutter, but it wasn't enough. We needed an endmill that would minimize cutting forces as much as possible. This would eliminate the flexing and hopefully improve tool life."

Evan Duncanson, milling application specialist at Emuge-Franken, went to work with his team and engineered and manufactured a special.

"We basically combined two of our standard tool geometries into one," he said. "Our intent was to replicate what the customer was using but put our own spin on it. So our technical team in West Boylston, Massachusetts, went to work developing the best design and microgeometry possible for the application, ultimately delivering an extended-reach, 10 mm (0.394"), four-flute endmill with a series of NF-style chipbreakers along its length and our ALCR coating for wear resistance."

Within the first day of use, Coulter saw a big difference in tool life.

"I ended up making 3,000 parts on the first job," he said, "and the new tool still looked good. You could tell right away by the sound that it was a lot freer cutting than the last endmill. I'm not privy to how they made it, but I do know one thing for sure: It works. Over the past several years of trying different tools, I haven't seen anything that comes even close."

As with all successful drag races, Coulter's next step is to tweak the operating parameters in an attempt to squeeze more out of the new tool.

"It's an ever-evolving process," he said. "But for now, we're just enjoying the benefits as is, which I figure is at least 20 minutes per shift less downtime and a whole lot less money spent on carbide (tools). It's already well worth the higher price for a custom tool. But once we start dialing in the speeds and feeds to further increase productivity, I predict some very significant cost

savings."