Holemaking operations

Holemaking operations

January 2009 Shop Operations column

Drilling holes is the most common of all machining processes, and the tool most commonly applied to make them is the twist drill. Twist drills remove metal from holes and reduce the metal to chips in a fast, simple and economical process. Nearly 75 percent of the metal removed by machining is drilled. Drilling is often the starting point for other operations, such as counterboring, spotfacing, countersinking, reaming and boring.

All images: Pamela Tallman

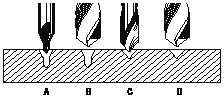

Making starter holes with a combination drill (A), a NC spotting drill (C) and a twist drill (B and D).

• Center drilling uses a short, rigid drill to make a cone-shaped starting hole for twist drills or lathe centers. Using a center drill ensures more accurate hole placement on the spindle axis than starting a twist drill on a flat work surface or center punch mark. Because twist drills flex and wobble when starting a hole, there is no certainty they will begin drilling on the spindle axis. There are two center drill designs: the NC spotting and centering drill and the combination drill and countersink. Both work well for starting holes, but only the combination drill makes properly shaped holes for lathe centers. Spotting drills are available with point angles of 60°, 82°, 90°, 118° and 120°. Combination drills, which have 60° point angles, drill a matching hole for lathe centers. They also drill an additional pocket for lubricant so the center does not burn. When using a spotting drill for a subsequent carbide twist drill, the spotting drill should always have a flatter angle than the carbide drill point so the twist drill's chisel edge makes contact with the work first—not the drill edges. For example, apply a 120° spotting drill for a 118° carbide twist drill.

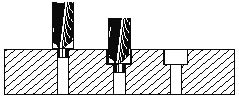

• Counterboring produces a larger, square-bottomed hole in the upper portion of an existing hole and provides space and seating for a bolt or cap screw head below a workpiece's surface. The cylindrical guide, or integral pilot, on the end of the counterbore ensures the enlarged diameter is concentric with the original hole.

When counterboring, a counterbore's pilot end enters an existing hole (left) and aligns the cutter, and increases the diameter of the existing hole (center).

• Spotfacing mills a flat area around an existing hole to make a flat seating surface for a bolt or washer and is usually necessary on castings and parts with sloping surfaces. Failure to spotface an uneven workpiece puts excessive stress on the bolt. On flat work, use a spotfacing bit or counterbore in a drill press, but on a sloping surface, because of the interrupted cut, use an endmill in a milling machine. Spotfacing cutters differ from counterbores because they cut larger diameter holes and sustain greater cutting forces, but they work the same way. Large spotfacing cutters have separate centers, allowing the same cutter to work in different hole diameters. On sloped surfaces, spotfacing is performed before drilling. This provides a flat surface on which to start the drill and makes it easier to follow-in straight. Remember to use a counterbore or milling cutter slightly larger than the washer, cap screw or bolt head diameter specified on the print.

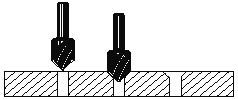

Countersinking uses a cone-shaped cutting tool to chamfer or bevel the edges of an existing hole.

• Countersinking uses a cone-shaped cutting tool to chamfer or bevel the edges of an existing hole, usually so flathead screws can be seated below the workpiece surface. Countersinks also deburr holes. Countersinking can be done with a hand-held drill or in a drill press, lathe or milling machine.

• Reaming enlarges an existing hole to a precise diameter and improves wall surface finish. It can be performed equally well in a drill press, lathe or mill.

• Boring enlarges the diameter of an existing starter hole with a single-point lathe tool. It can be performed in a drill press, but is more often done in a lathe or mill. Boring offers precise diameter control and perpendicularity. It typically produces smoother walls than drilling. CTE

About the Author: Frank Marlow, P.E., has a background in electronic circuit design, industrial power supplies and electrical safety. He can be e-mailed at [email protected]. Marlow's column is adapted from information in his book, "Machine Shop Essentials: Questions and Answers," published by the Metal Arts Press, Huntington Beach, Calif.