Rotary unions help deliver coolant to the cutting zone

Rotary unions help deliver coolant to the cutting zone

Machine tool users wouldn't benefit from through-spindle coolant (TSC) without rotary unions, which bring together spinning and stationary components to improve coolant delivery.

Machine tool users wouldn't benefit from through-spindle coolant (TSC) without rotary unions, which bring together spinning and stationary components to improve coolant delivery.

While flood-coolant systems spray coolant onto the workpiece near the cutting tool, TSC systems move coolant through the machine tool to the cutting edge. "If you have coolant coming through the center of the spindle, it's going to get right where it needs to go"—the bottom of a hole, for example, said Kevin Holdmann, owner of TAC Rockford (Ill.), a maker of rotary unions and other machine components. "But if you're spraying coolant from the outside, you're just hoping."

TSC proponents claim it offers a number of advantages compared to flood coolant. These include improved cooling and lubrication of cutting tools and machined parts, increased cutting speeds and tool life, reduced coolant consumption and more-effective chip evacuation.

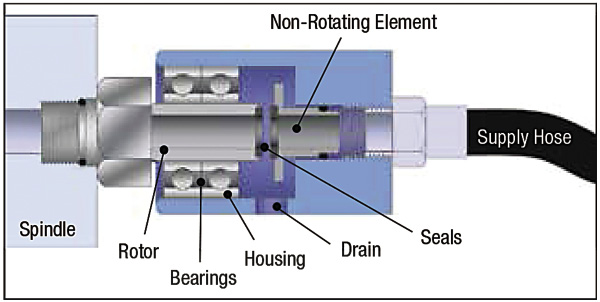

In TSC systems, coolant flows through a rotary union into the machine spindle. Rotary unions are mechanical devices that move fluids from a stationary source, such as a pipe, to a rotating machine part.

The key components of typical rotary unions used in machine tools are:

■ A rotor that spins with the spindle;

■ a stationary element that closes against the rotor;

■ a housing that connects the stationary element to the hose supplying the fluid; and

■ seals that contain the fluid in the union.

Deublin Co., Waukegan, Ill., sells its rotary unions mainly to machine tool OEMs, according to Matt Bell, the company's global machine tool market manager. "There are cases where we supply unions to customers looking to retrofit machines to add TSC," Bell added, "but the machines must have the framework to handle it." This includes a hollow spindle or at least a passage through it.

When choosing a rotary union for a particular machine tool, important considerations include the application's operating parameters (fluid type, pressure, temperature, and rotational speed and direction) and the type of connection to the machine.

Rotary unions without bearings (above) and bearing-supported ones (below) from Deublin feature the company's Pop-Off seal technology. The seals close when coolant pressure is applied to contain the coolant and "pop off," or separate slightly, in the absence of coolant pressure to allow dry machining.

Consider fluid pressure, for example. The higher the pressure, the more difficult it will be to seal the rotary union, Holdmann noted. So someone purchasing a rotary union for a high-pressure application must choose one with seal technology that's up to the task.

Deublin offers rotary unions with five different seal technologies. One, called AutoSense, senses the type of media—coolant, minimum-quantity lubrication or air—and automatically changes seal operation in response.

Rotary union buyers must also choose between offerings with bearings and those without. One-piece unions that connect the rotor and housing with one or more bearings are relatively easy to install and replace. On the other hand, unions that lack bearings are smaller, handle higher speeds and vibrate less. Their two-piece design makes mounting more difficult, however.

Then there's the consideration of whether coolant transfer will always be required during machining. Holdmann said there are situations where the presence of coolant in the work area might be undesirable, such as when machining certain materials. While some unions must have coolant flowing through them, others can handle these situations by running dry.

As for the latest developments in rotary unions, Bell noted the introduction of units with an integrated leak sensor that alerts an operator or a machine's programmable logic controller when the union is starting to wear or leak. In addition, "we have to account for higher speeds and coolant pressures," he said, adding that Deublin unions handle speeds up to 50,000 rpm and pressures as high as 210 bar (3,046 psi).

Is there any reason not to opt for TSC and rotary unions instead of flood-coolant delivery? "The only one is that it's more expensive," Holdmann said. "The rotary union itself might only cost $500, but the big cost driver is that the machine needs to be designed from the ground up for [flowing] coolant through the spindle."

So if you can handle the up-front cost and you're not already on the TSC bandwagon, now might be the time to hop aboard.