Spark success with EDM

Spark success with EDM

Machining difficulties melt away when electrical energy does the cutting.

When the going gets tough, the sparks fly at many machine shops. Those sparks are the signature of electrical discharge machining, a process called on by those tackling some of the biggest challenges presented by metal cutting.

Common techniques of this kind include wire EDM and sinker EDM. The choice between the two depends on the machining task at hand. Both have their strengths and downsides, and both have been enhanced by recent developments unveiled by companies that make EDM machines.

Suitable for machining conductive materials, EDM works by producing current discharges between two electrodes — a tool and a workpiece — with different polarities that are separated by a dielectric fluid. When the electrodes are close to each other, sparks are generated, causing high-temperature spikes that melt and remove material from the workpiece.

The tool electrode in the wire EDM process is normally a thin wire. Today, the diameter of an EDM wire is typically 0.01", said Eric Ostini, business development manager at Lincolnshire, Illinois-based GF Machining Solutions LLC, which sells EDM machines. As the EDM process melts material, the wire continues to unspool and move through the workpiece to cut the desired through-cavity shape. The process can include an initial roughing pass and a number of "skim" passes to improve the accuracy and surface finish of the cavity, he explained.

Wire EDM can include an initial roughing pass and a number of skim passes to improve accuracy and surface finish. Image courtesy of GF Machining Solutions

Unlike wire EDM, sinker EDM — also known as die-sinker EDM and ram EDM — normally is used to create blind holes or cavities. The shape of the tool electrode in sinker EDM is the inverse of the cavity shape that the machinist wishes to create. The electrode is plunged into the workpiece material, which is immersed in a dielectric fluid.

"You have to manufacture the electrode out of materials like graphite, copper and copper tungsten, and you need to machine the shape that you want to burn, typically on a CNC mill," said Brian Coward, EDM product manager at Makino Inc., a machine manufacturer in Mason, Ohio. "So the cost for sinker is going to be higher than it would be for wire."

In fact, he added, wire EDM is actually very cost-efficient compared with sinker.

"There is a cost for the spool of wire," Coward said, "but it's much cheaper than manufacturing an electrode."

Adding to the electrode costs of sinker EDM is the fact that more than one of them probably will be needed.

"Usually," Ostini said, "you're using one electrode as a rougher, then a second electrode as a semifinisher and maybe even a finishing electrode to get to the final size and surface finish that you'd like to achieve."

Pluses and Minuses

So why use EDM? When an application calls for very high accuracy and precision, there may be no other choice.

When EDM is employed, "we're talking about holding ±0.0002" in the operations," said George Brown, Northeast and Southeast regional manager at Pittsburgh-based Vollmer of America Corp., which sells EDM machines for making cutting tools. "Basically, it's on the same level as grinding, but with grinding you can't always get the precision contours that you can with EDM."

Wire EDM is employed to create parts with fine details and intricate geometries. Image courtesy of Makino

He also noted that EDM is a good fit for automated processes, including lights-out operations.

"There doesn't need to be someone there babysitting the machine," Brown said. With wire EDM, "as long as you have wire on the spool, the machine is going to run. But with a milling process, you've got to be concerned about how long your cutting tools are going to last."

On the other hand, EDM is slow compared with other machining options.

"EDM is the last process you want to use to make something because it's the most time-consuming process," Brown said. "So if you can make it another way, you probably want to do it on a mill or lathe."

Even though EDM machines might generate 300,000 sparks per second, Ostini noted, typical wire EDM speeds today are in the range of 37 to 42 sq. in. per hour, whereas milling speeds could be up to 200 sq. in. per hour.

Coward pointed out, however, that certain shapes and features simply cannot be milled. Or maybe you can mill them, he said, but if they're really intricate, they actually could take longer to mill than to make with a wire EDM machine.

"Wire EDM is very easy to program," he said, "and you can get things like very tight corner radii that you're not going to be able to do in a mill unless you go down to very small cutters and then go in and pick out those corners. But that's going to be very inefficient in terms of cost because those cutters are very expensive and they're going to wear fast."

In addition to its speed disadvantage in most cases, Brown mentioned another EDM downside that can be a cause for concern, especially in the aerospace industry. Although wire EDM makes it easier to put precise contours in titanium aerospace parts and wastes much less of that expensive material than conventional machining, he noted that the process also creates a heat-affected zone in parts, so aerospace users must make sure that the resulting properties in that zone are within allowable limits.

EDM in Use

However, Coward said that isn't the major issue it was 30 years ago when the heat generated by EDM produced microcracking that caused weak points in part material. He said that's no longer the case today thanks to more sophisticated EDM generators. As a result, he noted that sinker EDM is used to make a variety of jet engine parts that would be very difficult to produce any other way.

He also pointed out that wire EDM currently is used to make stents and other medical components with intricate designs and fine details.

Wire-saving iWire technology automatically reduces wire spool speed when cutting conditions change. Image courtesy of GF Machining Solutions

"Especially as implants get smaller and smaller," Coward said, "wire EDM lends itself to creating those types of parts."

Traditionally, a common application for EDM was creating mold cavities. But he said hard milling has supplanted EDM as the go-to option for this task.

"Now we can mill those (cavities) with the accuracy and finish that we need," Coward said.

However, there's still an important role for sinker EDM in mold making: creating support ribs in molds that help plastic parts hold their shape.

"Those are deep, thin ribs," Coward said, "and it's hard to get in and machine those with a mill."

Milling a deep cavity that is very thin would require a very small endmill capable of reaching the area to be cut.

"Depending on how small the endmill is, you can only go so deep because eventually you'll get to a stress point that will cause it to break," Ostini said. "Whereas with sinker EDM, you could go 4" deep (to create a feature) only 0.03" thick."

In addition, he noted that wire EDM can be used to create very thin through cavities that normally would be beyond the capabilities of other machining options. He also pointed out that a milling machine cannot produce sharp corners inside a cavity or make a deep, sharp-cornered cavity. He explained that is because endmills have diameters rather than sharp edges, so they would leave radiuses in the corners of cavities. With sinker EDM, on the other hand, users can create electrodes with sharp edges that will produce the desired sharp corners.

Another attractive feature of EDM is its ability to melt its way through the most challenging materials.

"As materials get harder and harder today, milling machines have to become beefier and stronger to cut through these materials accurately," Ostini said. With EDM, however, "we are using a spark that can get to almost 20,000 degrees Celsius, which means we are not worried about the hardness of the material."

Recent Advances

Today, wire and sinker EDM users also are benefiting from recent developments aimed at making the processes more economical and easier to use. One such development is the introduction of iWire technology by GF Machining Solutions. Ostini said iWire automatically adjusts the speed of a wire-dispensing spool to match cutting conditions at any given moment. If the thickness of a material being cut suddenly went from 3" to 0.5", for example, he said most EDM machines would have to be adjusted manually to slow the wire spool speed accordingly. By contrast, he explained, iWire would sense the change in material thickness and automatically make the appropriate adjustment. Prompt automatic changes of this kind can reduce wire consumption in a typical EDM process by 30% to 40%, he said.

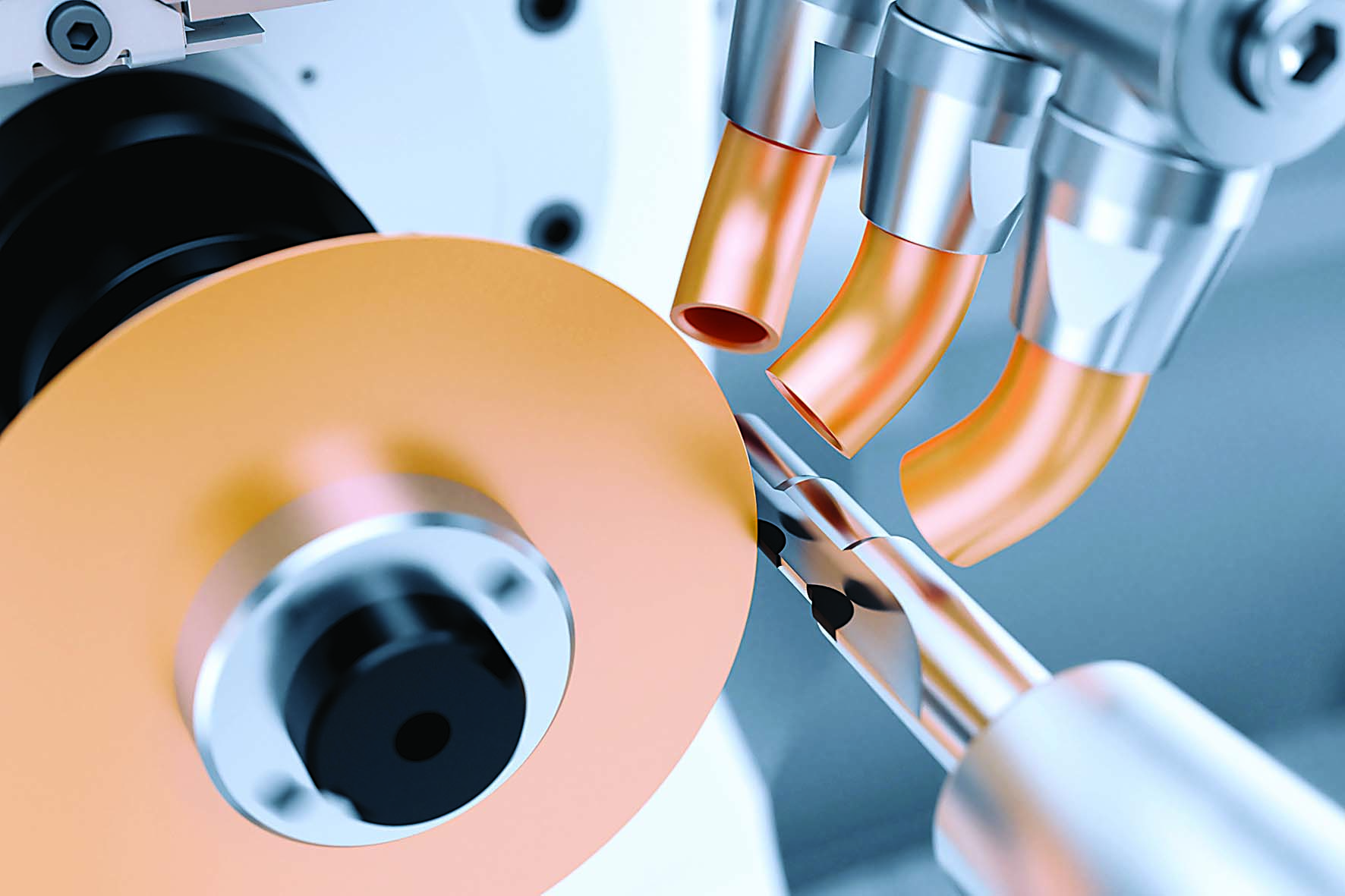

The VHybrid 260 combines a grinder and an EDM generator for toolmaking applications. Image courtesy of Vollmer

Another noteworthy development in EDM technology is the new Quick View Dynamic Content Assistant, or QV Assist, part of an update to Makino's Hyper-i wire EDM control. In the control window, QV Assist automatically displays whatever information operators need that relates to the current machine status. When the machine is running, for example, QV Assist will display information like remaining wire and time in the cut.

"In the old Hyper-i, you had to know what page to go to to find that information," Coward said. "The idea behind QV Assist is to bring that information up to the operator. That is going to assist newer operators and less experienced EDM guys in learning how to run the machine."

To improve sinker EDM processes, Makino also has introduced the Adapti-Spark Function, or AiSF, an adaptive control function that automatically adjusts the discharge current and "jump" settings (those that relate to the electrode's up-and-down movements along the z-axis) based on machining conditions. He said AiSF can cut EDM cycle time by 15% and reduce electrode wear by 80%, which could eliminate the need to make a second or third electrode to machine a shape.

For toolmaking applications involving polycrystalline diamond, Vollmer recently unveiled the VHybrid 260, a machine that combines a grinder with an EDM generator. The grinder can be used to produce the carbide part of a tool while the EDM process shapes the PCD tip, which is difficult to grind. Brown explained that the VHybrid 260 erodes PCD with a disk-shaped electrode made of copper tungsten in a process similar to sinker EDM.

Introduced at IMTS last year, he said the VHybrid 260 could be a game changer for toolmakers struggling with the challenges of machining PCD.

"I am excited about the machine and how it's going to make manufacturing of PCD tools much easier," Brown said.