Stress Management

Stress Management

High-performance aluminum-alloy workpieces are prone to residual stresses that can lead to part distortion. This article reviews the milling tools and practices that affect these stresses. Some tools and practices alleviate the stress, while others allow the machinist to mill the part without adding more stress.

When milling high-performance aluminum alloys,the best way to prevent part distortion is to control residual stresses.

Residual stresses in high-performance aluminum alloys pose extreme challenges to customary milling methods. In forgings or plate stock, these tensile or compressive stresses originate in deformation of the material during part fabrication and are released when the surface of the part is disturbed. Heat-treating an aluminum workpiece or machining it with endmills 1" in diameter or larger usually releases residual stresses in an uncontrolled manner. The result is part distortion.

7000-series aluminum materials such as 7050, 7055, and 7150 are particularly vulnerable to residual-stress problems. Many metalworking shops avoid jobs involving these materials because they are notorious for causing production difficulties. Other shops, however, are discovering that they can minimize part distortion by using residual-stress-management (RSM) techniques to control or reduce stress in a predictable way.

Distortion Mechanism

Although residual stresses are inherent in the work material, they may be amplified by induced stresses, such as heat and cutting forces. 7000-series aluminum is very susceptible to heat due to alloying agents in the material. If the cutter is ground improperly, or if the feed rate and speed don't correlate, the poor shearing action in the cut will induce stress into the part. Chatter caused by cutter walk may induce stress to the point where it bows or twists the part.

Distortion of a 7000-series aluminum part during processing is caused by stresses induced by traditional manufacturing techniques. These techniques often fail to control surface core stresses that serve as a release mechanism for residual stresses in the material. Because of their over-reliance on past practices in machining aluminum, machinists may choose inappropriate processing methods to mill and heat-treat 7000-series alloys. Unless machinists use the proper machining and heat-treating techniques, they won't be able to control the release of residual stresses in the workpiece material that lead to part distortion.

The RSM techniques discussed below apply to the milling of high-performance aluminum alloys as well as other aluminum materials (such as 2024-T3) using conventional NC machines. Although high-speed machines are being used to mill aluminum, the less sophisticated machines still are more common.

The machine tool should permit all operations to be performed on the part in the same setup. Using a versatile machine eliminates the need to move or refixture the part, thereby avoiding induced stresses due to the pressures of clamping fixtures and part handling. If a less versatile machine is used, the need for multiple setups will increase the stresses in the part. The fixture must clamp the part securely and give full support under the work. Overhang should be kept to a minimum.

On conventional NC machines, HSS, 8%-cobalt-HSS, or 10%-cobalt-HSS cutters are recommended. When a cutter less than 1" in diameter is used, controlling residual stresses isn't a significant problem. For best results with a cutter 1" in diameter or larger, use a 3-flute endmill with a 37° helix. A 3-flute cutter has a heavier feed-rate capability than a 2-flute cutter. Although more flutes restrict chip space, they remove more chips per revolution and provide other benefits.

The recommended 37°-helix-angle cutter removes more material than a conventional 30° cutter can. The 37° angle allows the tool to remain in contact with the part at all times and helps prevent the cutter from "walking" in the cut. This provides optimum shearing action, lower cutting forces, and better chip clearance. With a helix angle larger than 37, the cutter wouldn't have this shearing action, and chips would tend to load up.

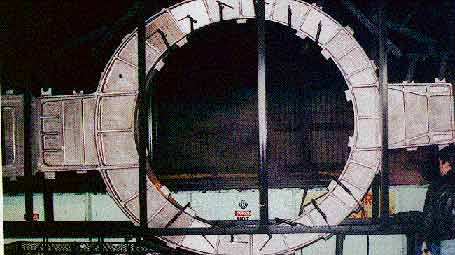

Residual-stress-management techniques were used for total control in machining this aircraft-engine support bulkhead. The 7075 aluminum part was produced to print (within 0.060" roundness and 0.030" flatness) with no distortion.

The primary relief angle should be about 8°, and the secondary clearance angle should be about 12°. This provides enough chip clearance to prevent chips from backing up. The rake angle should be ground at about 12° positive, and the dish angle should be less than 1° in order to provide stability at the bottom of the cut when plunging.

Chip slides should be intact, all the way to the tip of the cutter, to allow the material to be sheared and the chips to curl away from the tool and the part. A chip slide is the trough in the gullet of the flute where chips flow along the flute's helical twist. Chip slides that extend all the way to the rake angle allow uninterrupted chip flow, which is a critical requirement to attain effective machining rates.

The rate of cutter wear depends primarily on cutting speed. When the rake angle along with the chip slides (the true rake angle) is positive, then cutter force and cutter temperature will decrease 10% for every degree that the rake angle increases in the positive direction. Therefore, an endmill with a larger rake angle can handle higher cutting speeds without introducing more heat (and hence more stress) into the material.

Cutting Parameters

Lower cutting speeds on conventional NC machines reduce wear at the cutting edge, prolong tool life, and minimize machine-induced stresses during the milling of 7000-series aluminum. When an HSS or cobalt-HSS cutter is used, material suppliers typically recommend a rate of 400 to 800 sfm for aluminum parts.

Once the speed is calculated, the feed rate can be determined. Running the machine at 800 sfm, for example, the machinist could maintain a feed rate of approximately 45 to 50 ipm. A direct correlation between speed and feed is needed to maintain the chipload required at lower speeds on conventional NC machines. A key consideration is the thickness of the chip taken by each tooth. To avoid tool breakage, the material-removal rate should fall between 0.025 and 0.032 ipr. When the maximum chipload value is used, a 2-flute cutter will have a chipload of 0.0125 to 0.0135 ipt, while a 3-flute cutter will have a chipload of 0.008 to 0.011 ipt.

Feed rates should be continuous and should not be reduced below the programmed rates in attempts to extend tool life or improve surface finish. Never allow the tool to dwell in the workpiece. Prolonging the cutting causes localized heat, which amplifies the residual stresses within the part. With the appropriate combination of speed and feed, a 3-flute tool with the proper geometry can last from 200% to 300% longer than a conventional 2-flute cutter.

Milling Approach

Climb milling is another practice that promotes effective RSM. Conventional milling, also known as up milling, tends to lift the workpiece from the fixture. Because the cutter rotates in the opposite direction of the feed, the opposing forces create additional stresses within the material.

In climb milling, or down milling, the work is fed in the same direction as the rotation of the cutter, and forces are directed downward. Because the workpiece is forced against the surface to which it is clamped, climb milling is suitable for machining 7000-series aluminum workpieces that are thin or hard to hold. Climb milling is more practical for machining deep, narrow slots, because the cutting action allows the tool to cut without springing under a heavy force. The cutter teeth can bite into the material with a good shearing action that helps overcome cutter forces and induced stresses.

Another consideration in selecting the milling approach is chatter. The rapid, elastic vibration that appears between the tool and the workpiece is detected by marks on the part surface. Chatter is a danger signal of possible tool chipping or fracture. Remedies include eliminating uneven motion and increasing the rigidity of the fixture. Chatter typically isn't a problem with climb milling, because there are no opposing forces. It is less likely with low cutting forces, thick chiploads, and well-designed cutters with high rake angles and ample relief angles.

Balanced Machining

Metal-cutting operations that generate heat, and thereby add induced stresses to the residual stresses in the material, should be distributed around the part rather than performed sequentially in adjoining areas. Such nonsequential programming of operations helps control residual stresses that cause part distortion. This is the same concept autobuilders use to bolt cylinder heads to blocks. Starting at the center of the head, they tighten the bolts nonsequentially from side to side to distribute the stresses in the head and to ensure that the head is pulled down evenly against the block.

Let's say a 7000-series aluminum workpiece requires a series of pockets to be milled. If the machinist removes material from every other pocket, it disrupts the bridges that allow stresses to move between regions of the workpiece. When the remaining pockets are machined, the distortion is reduced or nonexistent because the stresses in the adjacent pockets already have been reduced and redistributed. This allows the part to relax and minimizes part distortion. A finish cut also helps compensate for part distortion remaining after the first cut.

After heat-treatment, balanced machining operations should be applied for all material-removal processes. A "flip-flop" operation from front to rear and top to bottom, rather than from top to front to rear to bottom, will help achieve balanced machining. Flip-flop allows the part to be recentered so that equal amounts of material can be removed. Because the part is refixtured directly over previous fixturing points, the machinist has control over induced stresses.

Heat-Treatment

With RSM techniques, residual stresses in 7000-series aluminum can be controlled in machining operations prior to heat-treatment, but stresses are inevitably introduced during in-solution or in-air heat-treatment. Therefore, it's almost always better to machine the part before heat-treatment. The complexity of most parts allows for rough milling before heat-treatment, with the final grinding operation done after heat-treatment to remove stresses.

For a part made of 7000-series aluminum, proper racking is particularly important for support during heat-treatment and quenching. Improper racking may add induced stresses to the residual stresses in the material. Annealing the part minimizes these stresses, but it is not a cure-all by itself.

Proper racking helps eliminate induced stresses that cause canning, twisting, or bowing of the part. These stresses are more of a problem in forgings than in other semifabricated parts because of forgings' wide variety of shapes and nonuniform cross sections. For example, forged parts that are 5' to 25' long and 2' to 3' wide with heavy cross sections must be horizontally quenched. Horizontal quenching allows the thicker portion of the part to be immersed in the quenching fluid first, thereby ensuring that a large area of the part is cooled simultaneously. Vertical quenching would cool a much smaller area at one time, and the difference in temperatures between the cooled section and the heated section would promote warping. By using RSM techniques during heat-treatment and quenching, part distortion can be minimized and blueprint specifications can be readily met.

To successfully mill and heat-treat 7000-series alloys and other aluminum materials that are difficult to process, all these RSM techniques must be implemented throughout the process. With proper control of residual stresses, machinists can handle these materials easily and efficiently while optimizing part accuracy and eliminating scrap.

2-Flute vs. 3-Flute Endmills

Tools commonly used for milling 7000-series aluminum alloys include roughing, finishing, semiroughing, insert-style, and specialty cutters. These tools may have from 1 to 6 flutes and helix angles ranging from 0 to 60.

In theory, aluminum can be machined with endmills having 3 or more flutes as long as the radial depth of cut is light, no pockets are cut, and no plunge milling is done. But in practice, very few operations meet these criteria. If a machinist tries to take too heavy a cut with a 4-flute endmill, the tool could quickly turn into a "lollipop" covered with melted aluminum.

To avoid such problems when milling aluminum, machinists typically use a 2-flute endmill. It has ample room for chip evacuation and is effective for plunging and ramping. Corner radii can be easily ground on this tool.

However, a 2-flute endmill has a tendency to "walk" in the cut, because it is less rigid than endmills with more flutes and larger core diameters. In slotting operations, a 2-flute endmill often leaves one of the two walls with an inferior surface finish.

When milling aluminum, a 3-flute cutter offers significant advantages over a 2-flute cutter. With more flutes, vibrations are reduced. A 3-flute endmill has a stronger core diameter for less deflection and better cutting-edge support, providing straighter plunge milling. Because more cutting edges are in contact with the workpiece, a 3-flute tool is more rigid and less likely to "walk" in the cut. Reduced deflection also improves tool life and workpiece finish.

Until recently, standard tools with 3 or more flutes were available only with geometries intended for steel. These cutters had helix angles from 25 to 30. Because they lacked sufficient room for chip clearance, these tools generally yielded unsatisfactory results.

However, Hanita Cutting Tools Inc. has developed a 3-flute endmill with a geometry that makes aluminum easy to machine. The cutter uses a 37 helix for reduced-force cutting action and faster chip evacuation. Tool edges are specially treated to avoid chatter and provide superior surface finishes. The cutter's rake and relief design improve edge strength and facilitate regrinding. A wide-open end-gash design speeds chip removal and makes the tool effective for plunging and ramping applications. A highly polished rake angle prevents chip adhesion.

With a 3-flute endmill, feed rates can be 50% to 70% higher than those used with a 2-flute cutter, regardless of the type of milling cut. In roughing cuts, for example, a good endmill can remove 6 cu. in. of material per horsepower. Therefore, on a 15-hp machine, the tool can remove 90 cu. in. per minute, or 1.5 cu. in. per second.

About the Author

Louis Caldarera Jr. is senior engineer scientist at McDonnell Douglas Corp., Long Beach, CA, and serves on the advisory board of Hanita Cutting Tools Inc., Mountainside, NJ.