Despite a shop’s best efforts, machine tools and other shop equipment break sometimes. But preventive maintenance (PM) can drastically reduce the frequency and the extent of the damage. Most machine tool builders and other equipment providers will provide the necessary maintenance steps to keep equipment up and running, but how those steps are taken is up to each shop.

An Inside Job

Component manufacturer Sterling Instrument handles virtually all maintenance matters internally, from PM on its machine tools to plumbing, HVAC and groundskeeping work at its New Hyde Park, N.Y., facility.

“I came from a bigger facility where there was no maintenance program, and machines would power down or jam up because nobody would do even simple things, such as checking the way lube,” said Shop Foreman John Lowe. “Production would slow down because of improper maintenance, and that’s something that’s easily avoidable. I guess our program was kind of born of frustration.”

Sterling’s program uses physical logs on the side of each machine, based on OEM maintenance requirements. The shop monitors coolant level and viscosity and oil levels in all areas of the machine once a week, cleans the coolant tank and changes filters yearly and checks and addresses everything on an as-needed basis every morning during machine warm up. The system has effectively eliminated any machine downtime caused by poor maintenance, according to Lowe.

North Canton, Ohio-based machine shop Stark Industrial LLC also opts to manage nearly all maintenance in-house.

“From a manufacturing standpoint, basically, none of our maintenance is outsourced,” said Manufacturing Engineer Jonathan Wilkof. “We outsource maintenance on our overhead doors, have service contracts for heating and air conditioning, have a service that calibrates our granite plates and contract out some of the more technical machine repairs, but, other than that, we have a system to take care of most maintenance ourselves.”

At one time, Stark shut down during the last week of the year to break down all the machines and see what work needed to be done. Stark still dedicates the last week of the year to maintenance, but it also established regular maintenance schedules for each CNC and manual machine, according to Wilkof.

“We found that, to meet customer deliveries and requirements, we need to have everything available at all times,” he explained, “so we have individual booklets at each machine that detail what maintenance should be done and on what schedule, be it weekly, monthly, annually or however it works out. We also include supporting information—either from the machine manual or from other sources—that the person doing the maintenance may need to refer to, so everything is available at the point of service.”

Liquid Controls, Lake Bluff, Ill., relies on its facilities manager and his staff to handle all PM, according to Manufacturing Engineer Mike Deren, and between fastidious attention to detail and close coordination with the production staff, the manufacturer of liquid measurement meters and accessories rarely runs into a problem it can’t fix.

“Even though we sometimes find ourselves pushing the machines to make production quotas,” Deren said, “we don’t run into too many problems we can’t handle ourselves.”

Courtesy of Sterling Instrument

In addition to regular maintenance on the machines themselves, Sterling Instrument keeps its shop as clean and free from clutter as possible.

Replacing worn components like bearings and electrical items is a regular occurrence, especially on older machines, he explained, and is handled in-house as issues arise.

Liquid Controls’ maintenance program typically involves shutting down one machine at a time for a routine overhaul on an annual basis. Regularly scheduled service allows production schedules to be adjusted accordingly, and, when one machine is down, the operators are free to assist in other shop operations.

“I’ve worked in shops where there was no PM,” Deren said. “When the machine broke down, that’s when it got serviced. That’s just not a good way to run things. A lot of our machines are close to 20 years old, and some of them run better than some newer machines I’ve seen in other shops, because we try to stick to that strict maintenance schedule.”

Contract Work

While in-house maintenance has its advantages, even its proponents admit there are drawbacks. Any issues outside the scope of what the shop is equipped to handle can be costly and time-consuming in the absence of established service contracts. Furthermore, small shops may not be able to realize the advantages of a full-time maintenance staff.

Rather than diverting internal resources to maintenance, PTooling, a shop with seven machine tools in Amherstburg, Ontario, trains its operators to handle routine maintenance like checking sump screens and changing air filters, but opts to invest in service contracts for the more-involved maintenance procedures.

“There just isn’t enough work to have a guy taking care of maintenance full-time,” said Marv Fiebig, company president. “Instead, we handle the routine maintenance and have the manufacturers train us on the monthly maintenance, but we contract out the big overhauls, anything beyond the scope of normal, routine stuff, to professionals.”

Typically, he continued, the outsourced operations involve complex activities such as turret and spindle alignment on machine tools, blade deviation adjustment and guide service on saws and government-mandated safety testing on lifting devices.

While the primary goal of any maintenance program is to keep machines running properly, PTooling’s maintenance regimen was developed with the additional goal of attaining ISO 9001 and API Q1 registrations, the requirements for which include formal, documented, systematic maintenance.

“It just made sense to structure it this way,” Fiebig explained. “I knew that, for example, come spring, I’d be calling to get our forklifts serviced, and in the fall we’d need to have the compressor serviced for winter, so we established a regular maintenance calendar. Now, training for routine maintenance has actually become part of our larger training matrix, making sure our guys know how to do things properly in between the big service calls.

“For us, maintenance is a critical function,” he continued. “We want to deliver quality products to our customers. We understand that having machines go down or produce substandard parts will put us out of business, so we depend on our machinery. It adds value, because our machines perform at such high levels. It’s costly and we end up beholden to someone else’s schedule to an extent, but I look at it as a small price to pay for the results.”

Keith Jennings, president and general manager of contract manufacturer Crow Corp., Tomball, Texas, said his shop also uses a hybrid approach to maintenance. In addition to a full-time, two-person maintenance staff, Crow purchases maintenance contracts for newer equipment.

“It’s something we view as a necessity,” Jennings said, “because it gets you access to that machine tool company. We spend a sizable amount on maintenance contracts, but they not only cover major issues above and beyond the scope of what my guys would normally handle, we also sometimes get parts at a discount, as well as other perks, depending on the manufacturer.”

Because a machine breakdown can cost tens of thousands of dollars, Jennings estimates that investing about $200,000 per year in PM saves his company two to three times that amount by reducing the risk of breakdowns.

A Routine Matter

Whether maintenance is handled in-house or outsourced via service contracts, some sort of regular, documented maintenance regimen plan is key to maintaining efficiency.

“Some machines we’ve purchased have come with suggested maintenance schedules,” said Stark Industrial’s Wilkof. “Those are very good, but the problem is that when we examined them, none of the forms matched—there was no consistency. The forms for different machines all had different information, and each one had to be filled out differently each time maintenance was performed.”

Courtesy of Sterling Instrument

Sterling Instrument keeps physical maintenance logs on each of its machine tools.

To address this, Stark collected all of the schedules and created a standardized, written maintenance log for all its machines. These logs include maintenance activities, the frequency at which they needed to be performed, explanations of each task and, if available, images from the machine’s manual to eliminate guesswork.

“The biggest problem I see other shops run into is that they never look at the manufacturer’s [maintenance] schedule,” Sterling’s Lowe said. “The manufacturer spent a lot of money developing a machine that works, so why reinvent the wheel? If you just follow their recommendations, your maintenance costs will go way down.”

Crow’s Jennings agreed that following the schedule set forth by the manufacturer is an important element to maintaining healthy machines, but that communication, both formal and ad hoc, between everyone on the shop floor can’t be overstated.

“Most equipment comes with a list of PM actions that the manufacturer expects you to do,” he said. “We basically establish a calendar with each of those tasks for every machine. Accountability is maintained in part by a checklist that gets signed and dated for each operation, but we’re also always in constant communication with one another, both in and out of meetings. In larger shops, larger facilities with more complex operations, a more formal maintenance program might be needed, but, in our case, the real key is communication.”

A Software Future?

While computerized maintenance management software systems exist, not all shops use them. Liquid Controls, for example, uses Maintenance Pro software to manage its maintenance calendars and records, allowing easy access to information, tracking all repair work, giving advance notice when PM is required and alerting operators to potential maintenance issues. Crow uses basic electronic calendar and spreadsheet programs to manage its maintenance programs, while PTooling, Stark and Sterling use physical records to track PM. However, that’s not to say shops aren’t seeking technological advancements.

“We are generally happy, but we’re always going to try to do better,” said Crow’s Jennings. “The markets that we serve get more demanding over time, so I could see us, over the next couple of years, needing to adopt a tighter, more formal maintenance program, possibly integrating a more robust, dedicated maintenance software program.”

According to PTooling’s Fiebig, more Web-based maintenance functionality from suppliers would be helpful. “For example, my son is a student in Thailand right now, and he programs a lot of our machines from that remote location,” he said. “If we could get more robust monitoring, where he would be able to assist with monitoring our machines remotely as well, we would continue upgrading the machine tool software in order to add that efficiency.”

Common Factors

Because shops are different, they handle maintenance differently. Even so, there are a few common factors everyone should be aware of—though they are not always intuitive.

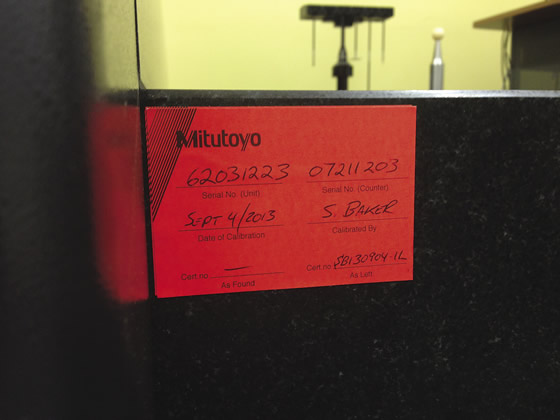

Courtesy of PTooling

Stickers, like this one on a Mitutoyo machine tool, allow PTooling to efficiently—and visibly—track maintenance schedules.

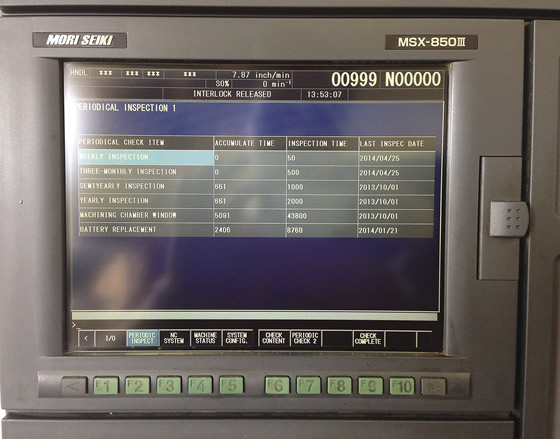

Courtesy of PTooling

Displays, like on this Mori Seiki MSC-850III CNC, give operators a running reminder of pending maintenance tasks.

“Don’t cheap out,” Fiebig said. “Of all the issues that I’ve had with machine shop owners, the biggest is that they think that buying a budget machine component for $6 will keep them competitive with a shop like ours that spends $16 plus maintenance on the high-quality version of the same component. You might save some money in the short term, but you’ll wind up making the same purchase again and again. To me, business common sense 101 should tell people that you can either spend a little but pay a lot—or you can pay a little more and make a lot.”

Crow’s Jennings said an oft-overlooked factor is the personality of the maintenance technician, explaining that his shop has interviewed (and occasionally hired) people with good technical abilities, but who did not bring the necessary foresight or sense of urgency to the position.

“When somebody is at a company in a maintenance capacity, people are going to lean on them for their expertise,” he said. “But you really need someone who not only has the knowledge, but knows how to collaborate with other shop personnel, who can organize and coordinate with other departments and do it without creating a bunch of stress or draining shop resources. Not everyone can do that.”

Stark’s Wilkof understands PM takes a significant amount of time and resources, so some shops might balk at the investment, but, when done correctly, the effects of PM are never seen—and that’s the point.

“There may never be a problem if you don’t do anything,” he said, “but you don’t know that, and none of the ways you can find out are good. Preventive maintenance is really like an insurance policy. Everybody feels differently about insurance, but I think it’s worth every penny we invest in it.”

“It’s very difficult for somebody to argue with me against PM,” Fiebig said. “It’s very unlikely you’ll be able to convince me that a given maintenance procedure has no value whatsoever. Suppliers today are starting to see that [PM] is something that can be a real moneymaker for them, so they are motivated to be as efficient as possible. Every business wants to make their customers happy, and in the case of preventive maintenance packages and services, companies can do that not by selling equipment, but by selling expertise. The more efficient they become, more efficient we become, and the happier everyone gets to be.” CTE

Contributors

Crow Corp.

(800) 642-2769

www.crowcorp.com

Liquid Controls

(800) 458-5262

www.lcmeter.com

PTooling

(519) 736-8654

www.ptooling.ca

Stark Industrial LLC

(800) 362-9732

www.starkindustrial.com

Sterling Instrument

(800) 819-8900

www.sdp-si.com

Related Glossary Terms

- computer numerical control ( CNC)

computer numerical control ( CNC)

Microprocessor-based controller dedicated to a machine tool that permits the creation or modification of parts. Programmed numerical control activates the machine’s servos and spindle drives and controls the various machining operations. See DNC, direct numerical control; NC, numerical control.

- coolant

coolant

Fluid that reduces temperature buildup at the tool/workpiece interface during machining. Normally takes the form of a liquid such as soluble or chemical mixtures (semisynthetic, synthetic) but can be pressurized air or other gas. Because of water’s ability to absorb great quantities of heat, it is widely used as a coolant and vehicle for various cutting compounds, with the water-to-compound ratio varying with the machining task. See cutting fluid; semisynthetic cutting fluid; soluble-oil cutting fluid; synthetic cutting fluid.