I love the cloud. My Word files and Excel spreadsheets are stored in the cloud, and my wife uploads cute pictures of the grandkids. No more worries about backing up the computer or about what will happen to our life’s data should it burst into flames. Best of all, I can access all my information from my smartphone, laptop or tablet whether I’m waiting in line for a cappuccino or sitting in a conference room.

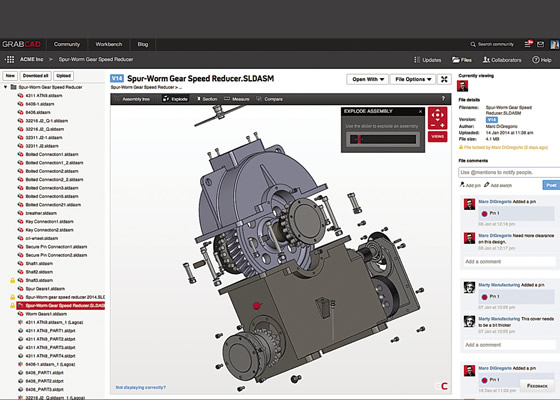

Courtesy of GrabCAD

A spur gear assembly drawn in SolidWorks and displayed via the GrabCAD virtual workspace. Comments from collaborators can be seen on the right.

Software developers love the cloud too. Microsoft, for example, offers subscriptions to its Office suite, making version upgrades and security patches as necessary as floppy disks. And the company’s Azure hosting platform could very well revolutionize the way businesses manage their information technology services. Starting at around $15 per month per machine, you can log on to Microsoft’s Web site, order a virtual server and deploy software to your company’s user community within minutes.

The software giant isn’t the only one. NetSuite, salesforce.com, Jive Software, Dropbox, Evernote—these are just a handful of the cloud-based software companies transforming the way we live and work. Borrowing from the late Steve Jobs, the cloud changes everything.

Cloud Confusion

One of the functions of the cloud is to provide software programs to users without the hassle of actually installing it. Instead, a Web browser or small bit of software known as a client is used to share information with a group of computers or servers. These servers are housed in one of thousands of data centers around the world, facilities with security measures in place and tended by IT acolytes dedicated to the care and feeding of huge mainframes.

Granted, cloud computing isn’t quite that simple. It requires a new way of thinking about software development and deployment. This might explain why CAD/CAM developers have been slow to embrace the cloud—but that attitude appears to be changing. One example is the release of San Francisco-based Autodesk Inc.’s first cloud-based design tool, Fusion 360.

For $40 per month or $300 annually, Fusion 360 subscribers have access to a 3D design tool with solid modeling and integrated CAM. Product Manager Anthony Graves said: “Fusion 360 is oriented toward manufacturing and product development. You get many of the same capabilities as AutoCAD, but users can also collaborate on product designs in the cloud, share drawings and photos, generate toolpaths and post-process to a CNC.”

The ability to collaborate on projects is one of the biggest benefits of the cloud, Graves pointed out. “You can share your design with co-workers or customers. All they need is a username and password to log in. Once online, users can review design changes or add drawings and notes. They can upload a photo from a smartphone or scan in a drawing made on a napkin. There’s no more need to email files because all the data is stored in one location. It’s much more efficient.”

Get Connected

Graves said this kind of “connective manufacturing” is difficult and expensive to achieve without the cloud. “The traditional software approach would have you write a custom application or proprietary solution to achieve this level of collaboration and efficiency. Cloud-based applications eliminate that. When you weigh costs and benefits, you’re going to see a lot of people move into the cloud for CAD/CAM.”

Rob Stevens, vice president of marketing and business development for GrabCAD Corp., Cambridge, Mass., agreed, even though his company doesn’t produce or sell its own CAD/CAM software. Instead, it offers a virtual cloud-based workplace where 1.5 million designers and engineers meet and share information. “We started as a CAD community, where engineers could log in to our system and access a free library of CAD models. More recently, we’ve launched GrabCAD Workbench, which is a PDM (product data management) system, but one that everyone can share and add to.” (In September, 3D printer manufacturer Stratasys Ltd., Eden Prairie, Minn., and Rehovot, Israel, agreed to acquire GrabCAD.)

Need a SolidWorks model of a CNC milling machine, an IGES file of a shipping container or an AutoCAD drawing of an LS3 engine block for your Corvette? These and half a million other CAD files are there for the taking. Instead of posting files to a public Web site, subscribers have access to a secure and private cloud-based sharing space. For $60 per month per user, companies can collaborate on CAD projects, manage file revisions and access control, view and markup drawings, automatically back up data and compare files to review changes during the design process.

Stevens said WorkBench is CAD-agnostic and allows companies to securely share drawings with suppliers and customers even when they work on different CAD systems or have no CAD at all. “There’s a Web viewer so users can open the CAD model, move it around, rotate and zoom, even measure features. They can’t edit the model, but they do have online access to all the tools necessary to develop a quote or review a product design.”

Cloud Teamwork

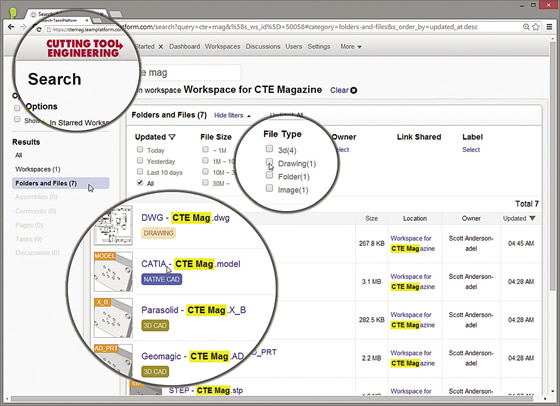

Another company jumping into the cloud is additive manufacturing equipment provider 3D Systems, Rock Hill, S.C. Scott Anderson, director of cloud solution sales and Geomagic Solutions, said the company’s TeamPlatform is for cloud-based collaboration and project management, including CAD users and anybody who’s working with 3D scan data. “Although it interfaces directly with our Geomagic software suite, it is not limited to proprietary file formats.”

This means Geomagic users can digitally scan a workpiece and upload it to TeamPlatform, where someone using CAD systems such as SolidWorks, Siemens NX or AutoCAD Inventor can access the file, check dimensions, perform cost analyses or propose design changes, then save their work to a platform neutral format, maintaining secure revision control throughout.

A sharing function gives invited users access to a project hosted on 3D Systems’ TeamPlatform, including 3D models and project tasks.

Users can search for data, such as files, in TeamPlatform and narrow the search based on file type, owner and other metadata. Companies can custom brand the platform with their company logos, as in this sample platform showing the CTE logo.

TeamPlatform’s file view provides Web-based visualization of files, including drawings, documents and 3D models. Invited users can download files, get file properties such as versioning, and use collaboration features to leave notes or comments.

“A prime example of this would be reverse engineering an airplane component,” Anderson said. “Say you have a damaged wing section and replacement parts are no longer available. You could scan the good wing, mirror it and export the model to TeamPlatform. From there, a supplier with the appropriate access could download the model and use it to fabricate a new component, regardless of which CAD platform they use in-house.”

Project managers can assign tasks to stakeholders through online work flows, which keep track of the who, what, when, where and why for various stages of design, manufacturing and inspection. All of this information is visible in the cloud, and such data is synchronized to each team member’s desktop computer, smartphone or tablet.

For those who wish to integrate cloud-based information to existing product lifecycle management, customer relationship management or enterprise resource planning systems, 3D Systems offers an application programming interface for both TeamPlatform and Geomagic. This allows programmers to “peek beneath the sheets” and extract pertinent information for use in these disparate software programs.

Get Wired

Another example of cloud-based CAD comes from engineering and technology firm Cadonix Ltd., Buckinghamshire, England, which offers Arcadia, a cloud-based application for automotive electrical designers. Business Development Manager Jon Collins said Arcadia is targeted at wiring harness manufacturers and OEMs, such as Leoni Wiring Systems and Delphi Automotive.

The application consists of two main modules. Collins said: “The first provides for schematic design and simulation. An engineer can draw a circuit, throw a virtual switch and analyze the results. Once the schematic is ready, we can pull that information into the harness side of the application and lay everything out in 2D format for assembly, automatically populating the harness bundles with connectivity data, terminal assignments, seals, connectors and coverings. We also produce a complete bill of materials, wire cutting lists and all of the documentation needed to manufacture the product.”

Like other cloud software providers, Cadonix offers a subscription-based, pay-as-you-go licensing model, but Collins said most customers opt to purchase the software and install it on one of Cadonix’s server farms. Users then access the software through a Web browser, eliminating the need for special client software. This sort of hosted environment is common in the cloud world. The Cadonix maintenance agreement covers patching, upgrades and backups, helping reduce IT costs.

Some customers install the software on their own servers, a sort of “private cloud” that utilizes a virtual private network or other secure connection for user access. Some may claim this arrangement is not true cloud computing, but Collins said the cloud is open to interpretation. “We don’t force our users to comply with any one particular architecture. It really comes down to how you address the customer’s needs, from both cost and data security standpoints.”

This last point—data security—would seem to be an important one, but everyone interviewed for this article agreed there is little concern among the user community over the security of the cloud, despite some highly publicized cloud storage security breaches. That should come as no surprise. Forbes reported last year that more than 50 percent of all businesses are already using the cloud, a 2014 report by the Pew Research Center claims 69 million Americans use online banking, and market intelligence firm iHS iSuppli predicts there will be more than 1.2 billion cloud-based storage subscriptions by 2017. Despite the recent excitement over nude photo hacking and department store credit card theft, the cloud is a far more secure place to store data than are personal computers or even many corporate servers, provided strong passwords are used and software security updates are performed regularly.

Distributed CAD Computing

Collaboration platforms, software deployment and data storage are clearly the leading cloud applications, but Nick Sidorenko envisions a wider application for cloud technology. As president of Cloud Invent, a software developer with offices in Akko, Israel, and Pembroke Pines, Fla., Sidorenko said the most interesting aspect of cloud computing is its use as a powerful computer. “Suppose you have a huge geometric model, one with a large number of parametric values. Desktop computers are not powerful enough to efficiently handle the number of calculations needed to process all the variables.”

A better alternative, he said, is distributed computing via the cloud. By utilizing hundreds or even thousands of computers, all working in parallel, even the most complex mathematical models can be broken into bite-sized pieces and distributed across the cloud for processing. In this way, Sidorenko claims, the next CAD revolution—one that marries 3D parametric modeling and 3D direct modeling into a single, easy-to-use application—can be achieved.

Sidorenko is just getting started. His company secured several investors earlier this year and will release its first product this fall. Cheetah Solver is a plugin for AutoCAD that Sidorenko claims speeds geometric calculations, even without the cloud-based parallel computing he envisions. If he’s right, the cloud may soon become a supercomputer, one CAD/CAM users can utilize to not only store models and collaborate on projects, but efficiently process information as well, no matter how large or complex the job. CTE

Contributors

Autodesk Inc.

(800) 964-6432

www.autodesk.com

Cadonix Ltd.

+44-1795-842-702

www.cadonix.com

Cloud Invent

(954) 342-6123

www.cloud-invent.com

GrabCAD

(617) 825-0313

www.grabcad.com

3D Systems

(803) 326-3900

www.3dsystems.com

Related Glossary Terms

- backing

backing

1. Flexible portion of a bandsaw blade. 2. Support material behind the cutting edge of a tool. 3. Base material for coated abrasives.

- centers

centers

Cone-shaped pins that support a workpiece by one or two ends during machining. The centers fit into holes drilled in the workpiece ends. Centers that turn with the workpiece are called “live” centers; those that do not are called “dead” centers.

- computer numerical control ( CNC)

computer numerical control ( CNC)

Microprocessor-based controller dedicated to a machine tool that permits the creation or modification of parts. Programmed numerical control activates the machine’s servos and spindle drives and controls the various machining operations. See DNC, direct numerical control; NC, numerical control.

- computer-aided design ( CAD)

computer-aided design ( CAD)

Product-design functions performed with the help of computers and special software.

- computer-aided manufacturing ( CAM)

computer-aided manufacturing ( CAM)

Use of computers to control machining and manufacturing processes.

- gang cutting ( milling)

gang cutting ( milling)

Machining with several cutters mounted on a single arbor, generally for simultaneous cutting.

- milling

milling

Machining operation in which metal or other material is removed by applying power to a rotating cutter. In vertical milling, the cutting tool is mounted vertically on the spindle. In horizontal milling, the cutting tool is mounted horizontally, either directly on the spindle or on an arbor. Horizontal milling is further broken down into conventional milling, where the cutter rotates opposite the direction of feed, or “up” into the workpiece; and climb milling, where the cutter rotates in the direction of feed, or “down” into the workpiece. Milling operations include plane or surface milling, endmilling, facemilling, angle milling, form milling and profiling.

- milling machine ( mill)

milling machine ( mill)

Runs endmills and arbor-mounted milling cutters. Features include a head with a spindle that drives the cutters; a column, knee and table that provide motion in the three Cartesian axes; and a base that supports the components and houses the cutting-fluid pump and reservoir. The work is mounted on the table and fed into the rotating cutter or endmill to accomplish the milling steps; vertical milling machines also feed endmills into the work by means of a spindle-mounted quill. Models range from small manual machines to big bed-type and duplex mills. All take one of three basic forms: vertical, horizontal or convertible horizontal/vertical. Vertical machines may be knee-type (the table is mounted on a knee that can be elevated) or bed-type (the table is securely supported and only moves horizontally). In general, horizontal machines are bigger and more powerful, while vertical machines are lighter but more versatile and easier to set up and operate.

- parallel

parallel

Strip or block of precision-ground stock used to elevate a workpiece, while keeping it parallel to the worktable, to prevent cutter/table contact.

- web

web

On a rotating tool, the portion of the tool body that joins the lands. Web is thicker at the shank end, relative to the point end, providing maximum torsional strength.