Avoiding machine crashes

Avoiding machine crashes

Everyone crashes, I was once told. It's likely true. However, not all crashes are created equal. There are fender benders that just break small tools, and then there are head-on collisions that ruin much more—including your day. CNC machine crashes are relatively easy to avoid. They often occur during setup and debugging. If you can recognize high-risk situations, you'll be in a better position to avoid them.

Everyone crashes, I was once told. It's likely true. However, not all crashes are created equal. There are fender benders that just break small tools, and then there are head-on collisions that ruin much more—including your day.

CNC machine crashes are relatively easy to avoid. They often occur during setup and debugging. If you can recognize high-risk situations, you'll be in a better position to avoid them.

Before discussing the mechanics of avoiding crashes, I'd like to highlight something many metalworking professionals already know: One of the most effective ways of avoiding crashes is to avoid being interrupted while programming and setting up. That's easier said than done, of course.

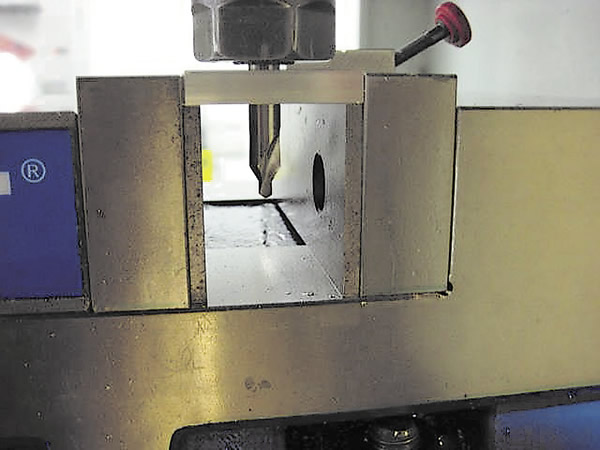

Gross Z negative errors in a program translate into gross machining errors. In this example, the center drill was mistakenly programmed to go Z-1.0 instead of Z-0.1, which resulted in a scrapped part. Machinists should visually scan a new program to check for these types of errors. All images courtesy J. Harvey.

Avoid moving around too much while in "handle jog mode." (Handle jog mode allows you to move the table around manually with a CNC machine.) I use it mostly for the bare necessities, such as edge finding, indicating and clearing the cutter. However, handle jog mode can be used for some simple machining.

Occasionally, I use handle jog mode to face the end of a bar or fly-cut blocks of material. However, I generally prefer machining parts under program control. It is relatively easy to forget which axis and feed increment you have engaged when you start cranking the feed handle, and it's a good habit to be cautious when you start cranking it. Turn the handle just one or two clicks to verify that the spindle is moving in the direction and at the feed rate you want.

Check the Z negative moves in a new program to see if they make sense. This is an easy way to avoid crashes. For example, if your first tool is a center drill and you are drilling a plate, the Z negative move for the center drill should be somewhere around Z-0.150. If the value in the program is something like Z-1.150, something is wrong.

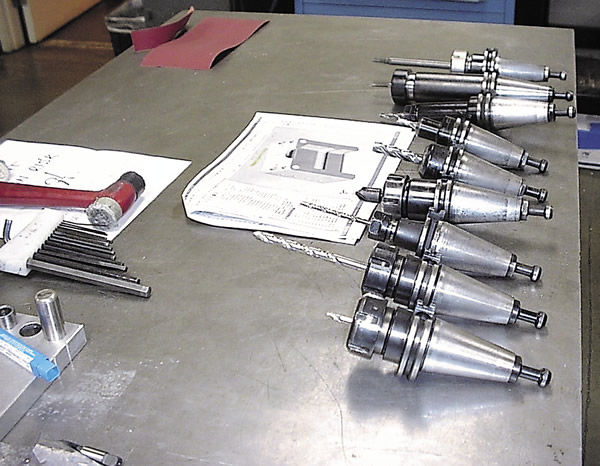

It's wise for machinists to physically lay out all the tools used in a program in sequential order before installing them in a machine.

You should also scan other Z negative moves in a program for drilling, reaming and tapping. The Z negative moves for those operations can be easily found within the canned cycles that execute them.

Perform a quick visual scan of feed rates. If you see something like F500. and are machining stainless steel, something is wrong, at least with the feed rate. Feed rates for machining stainless are generally from F10. to F20. An F500. feed would certainly break a cutter.

Also, visually check spindle speeds. Spindle speeds are sometimes incorrectly input in a program. It is easy for a programmer to add another zero to a spindle speed by mistake. Suppose a spindle speed for a reamer was meant to be 300 rpm and the programmer mistakenly makes it 3,000 rpm. In this case, the reamer would get fried if the mistake weren't found.

Before running a program, also make sure that all tool numbers are correct and that they have the correct corresponding "H" value, which calls up the tool-length offset for a specific tool. For example, in a section of programming for a specific tool, you would not want to see "T2 M06" followed by "G43 H2." Only after calling up T4 would you want to see G43 H4 in a program. I've gotten to the point where I shy away from letting other machinists run my unproven programs, because a lot of them won't take the time to do these simple checks.

No programmer can provide perfect programs all the time. I'll even go so far as to say that if I'm the machinist and I run someone else's program that results in a crash, it's my fault.

Tool numbers get screwed up in programs for various reasons. During program construction, programmers must decide what tools to use. Tools often get added or subtracted by the programmer. If the programmer fails to renumber the final tool selections in a program, confusion can occur while setting up the job.

I will conclude the topic about avoiding crashes next month.