Choosing the right boring tool

Choosing the right boring tool

Drilling, reaming and boring are the basic holemaking operations of machining. In simple terms, drilling creates a hole in a workpiece where there was no existing hole. Reaming and boring accurately enlarge holes that already exist.

Drilling, reaming and boring are the basic holemaking operations of machining. In simple terms, drilling creates a hole in a workpiece where there was no existing hole. Reaming and boring accurately enlarge holes that already exist.

Boring operations on turning machines are generally less complicated than boring operations on milling machines. With lathes, the boring tool is moved incrementally by the machine whereas with mills, the boring tool (boring head) must be adjusted to achieve the desired hole size. In theory, boring tools for turning can make any size hole as long as the bar will fit into the hole. Boring heads for milling machines, however, are limited to a specific range.

The Basic Boring Bar

Found in every machine shop, basic boring bars that accept carbide inserts work well in most applications and are economical.

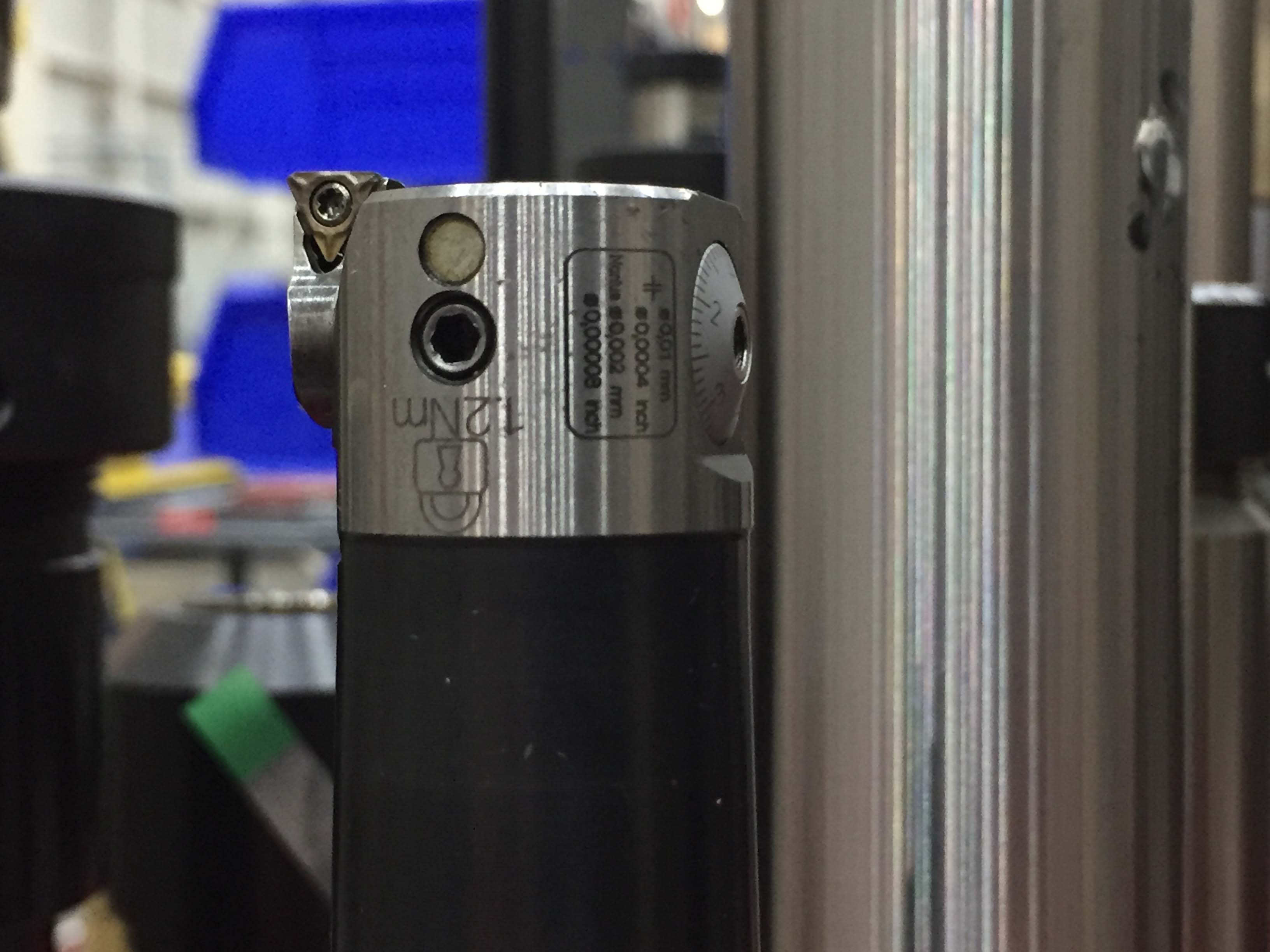

A fine boring head used for finishing close-tolerance bores. Heads like this one can be adjusted in 0.0004" increments. All images courtesy of Christopher Tate.

Unlike drills or reamers, single-edge boring bars have a single point of contact with the workpiece. As a result, the bar is unsupported, which sometimes leads to vibration, or chatter. Problems with chatter are the only significant drawback to these cutting tools.

Steel bars tend to chatter once the axial DOC exceeds 4 diameters deep. So, an end user would likely experience chatter on a 1"-dia. (25.4mm) bar if it protrudes from the turret by more than 4" (101.6mm). A machinist would say it has too much "stick-out."

Chatter Away

Chatter during boring operations on a lathe can be overcome. The easiest way is to apply a larger-diameter boring bar. However, a larger bar is not always an option and other means would be necessary.

Sometimes the solution is as simple as working with cutting speeds and chip loads to alter the cutting pressure on the tool. It is possible to increase tool pressure by increasing the feed rate, decreasing the cutting speed or doing both at the same time. Changing the radial DOC will also put more pressure on the tool. Sometimes users must adjust all of these variables to achieve success.

Because of their lower cost, steel boring bars are the most common, but other materials are also available. For example, cutting tool manufacturers have developed heavy-metal and carbide bars to fight chatter. Heavy-metal bars are made from tungsten alloys, which are denser than steel. These alloys work to damp vibration. Although heavy-metal bars are more expensive than steel ones, they can be applied at higher length-to-diameter ratios. Whereas steel allows a 4:1 ratio, heavy-metal bars can boost the ratio into the 6:1 or higher range with some speed-and-feed tuning.

Tungsten-carbide bars provide even higher depth-to-diameter ratios. Carbide bars are made by brazing a steel head that is machined to accept an insert onto a carbide bar. Carbide is extremely dense. It provides superior damping, allowing length-to-diameter ratios in the 8:1 or higher range.

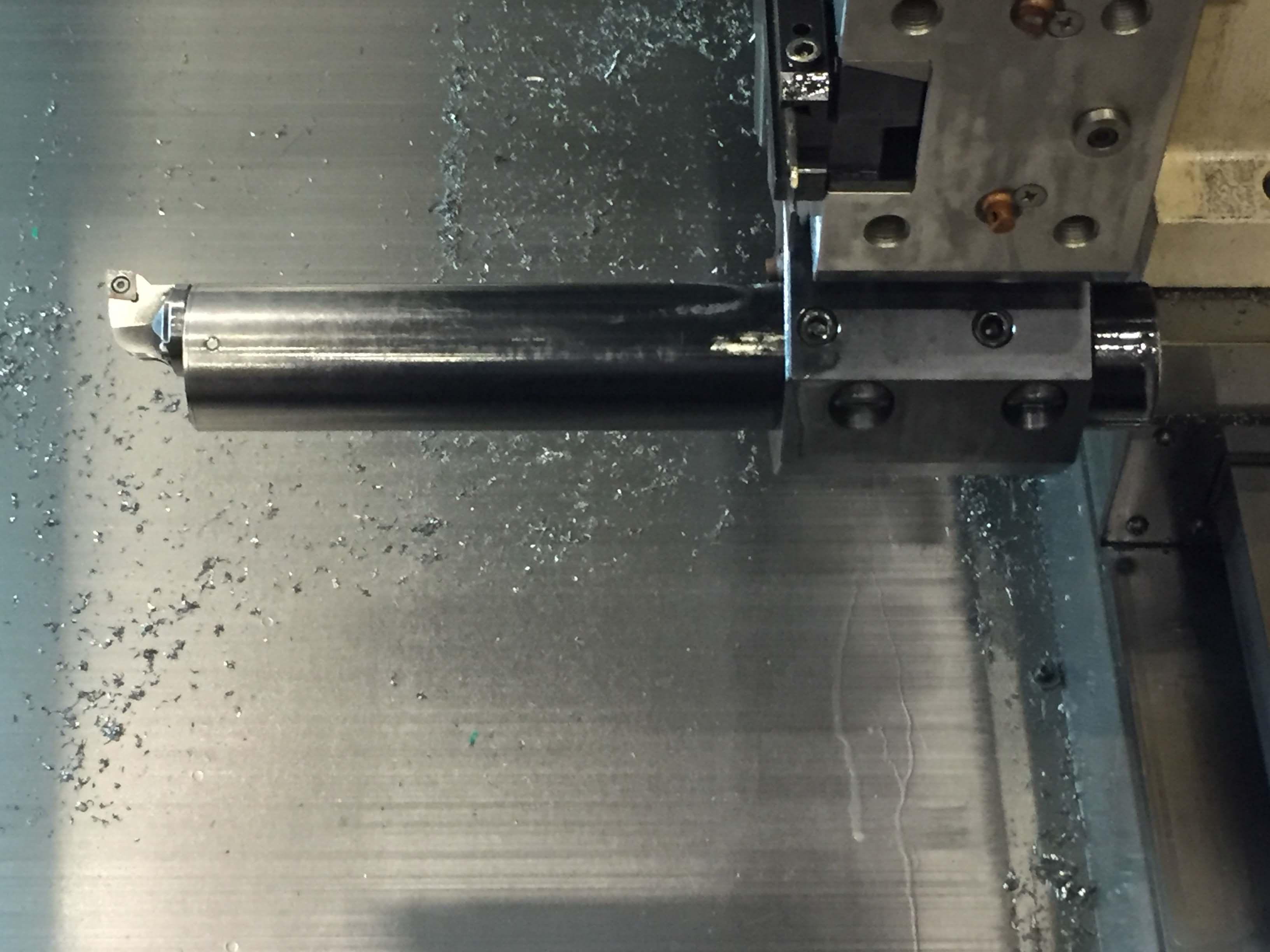

Vibration-damping bars have internal mechanisms that eliminate chatter. Because these bars can be expensive, buy them with interchangeable heads that accept different inserts.

Carbide bars above 1" in diameter are not practical because of the expense. In situations where carbide would be cost-prohibitive, a tunable bar may be warranted. As the name implies, these bars have an adjustment feature that enables a user to tune the bar to a specific application. An internal mechanism alters the natural frequency of the bar, preventing chatter and allowing very large length-to-diameter ratios. Some tool manufacturers have reported the ability to make cuts at 20:1.

Boring and Mills

Unlike the boring bar for a lathe, the tool used on a mill must be adjustable to achieve the correct size. Boring holes on a milling machine requires the use of an adjustable boring head, which adds complexity to the setup.

The most commonly used boring heads shift the boring bar closer to or farther away from the axis of the hole to achieve the desired hole diameter. These boring heads are inexpensive. Users can bore a large range of hole sizes with these heads because the boring bar can be mounted in several different

positions.

Boring heads are typically associated with conventional milling machines, but they can be used on CNC machines.

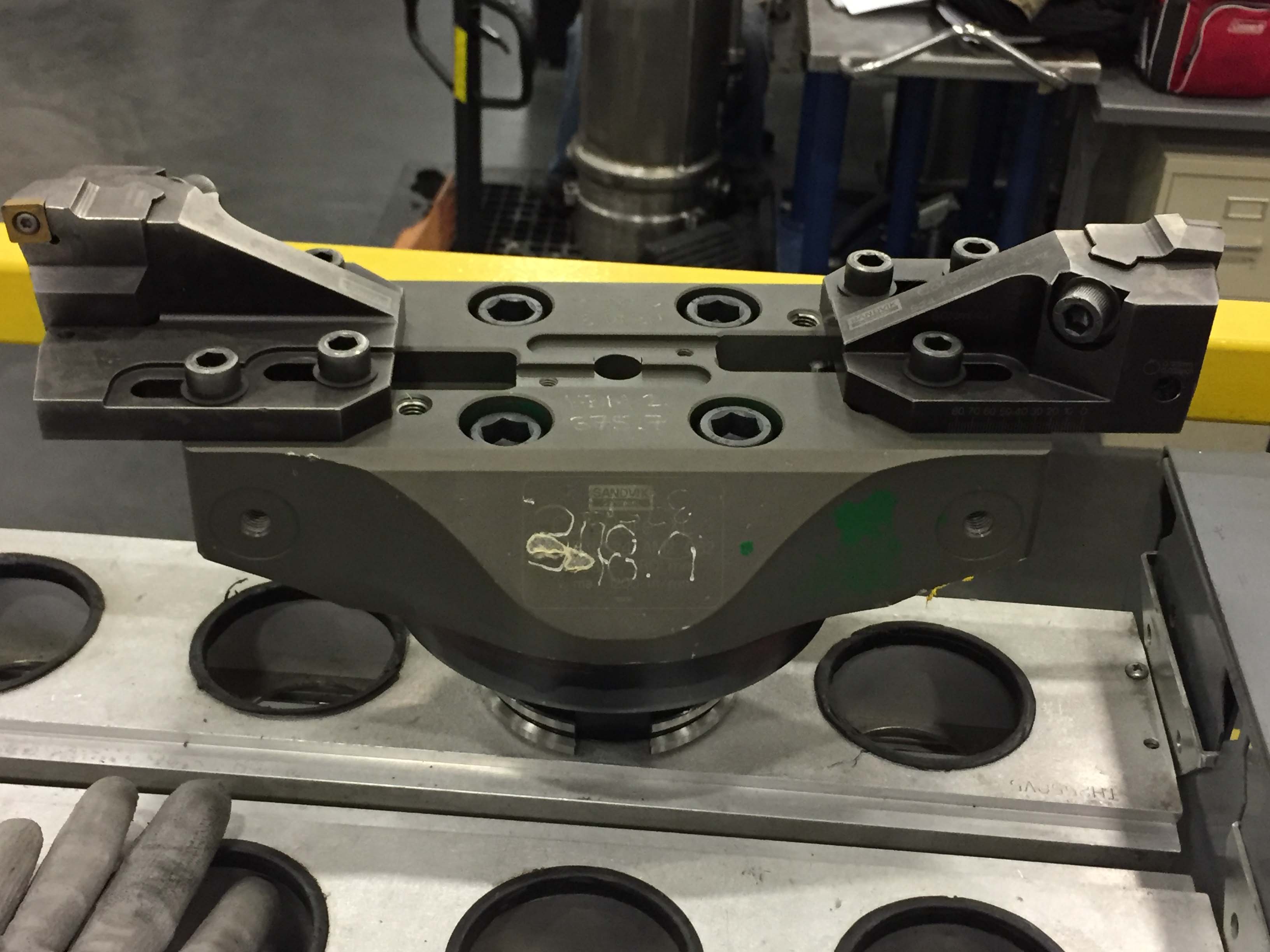

This twin-head boring bar can rough large bores on a horizontal boring mill.

You can engage more than one cutting edge when boring on a mill, unlike a lathe. Some boring heads are used frequently in high-production environments. Twin boring heads are set up one of two ways. In the first way, each cutting edge is set to the same diameter, allowing a fast feed rate. With the second method, the cutting edges are set on two different diameters, thereby removing more material per pass.

Finishing Touches

Twin-style heads are best-suited for roughing because they are not easily adjusted for those times that small incremental changes to the boring diameter are necessary. When finishing, it is better to select a finish-boring head to make those small adjustments to the diameter.

Finishing tight-tolerance holes often requires special boring tools that can be accurately adjusted in small increments. These boring heads are often referred to as fine boring heads—some can be accurately adjusted in increments as small as 0.0001" (0.0025mm). Fine boring heads come in several styles. Some utilize basic round boring bars and others utilize special insert holders. They are expensive and are typically reserved for boring holes with diametric tolerances less than 0.001" (0.025mm).

This small-diameter, vibration-damping bar has several cutting heads.

Boring operations and tools require machinists to pay as strict attention to details as other processes and cutting tools. Although many factors influence whether a boring operation is successful or not, adhering to the following rules will help ensure the desired results:

- Keep the workpiece materials well supported.

- Minimize unsupported tool length.

- Use the largest-diameter tool possible.

- Fight chatter by adjusting tool pressure before investing in more-expensive technology.