Maximizing with multispindles

Maximizing with multispindles

Before CNC lathes, most high-volume turned parts were made on multispindle, cam-driven screw machines. Setup times were long, and great skill was needed to design the cams and grind the cutting tools. However, by being able to perform a dozen or more operations simultaneously, they could produce hundreds—often thousands—of parts per hour. Whatever happened to those old mechanical monsters? According to Giovanni Principe, they're alive and well.

Before CNC lathes, most high-volume turned parts were made on multispindle, cam-driven screw machines. Setup times were long, and great skill was needed to design the cams and grind the cutting tools. However, by being able to perform a dozen or more operations simultaneously, they could produce hundreds—often thousands—of parts per hour.

Whatever happened to those old mechanical monsters? According to Giovanni Principe, they're alive and well.

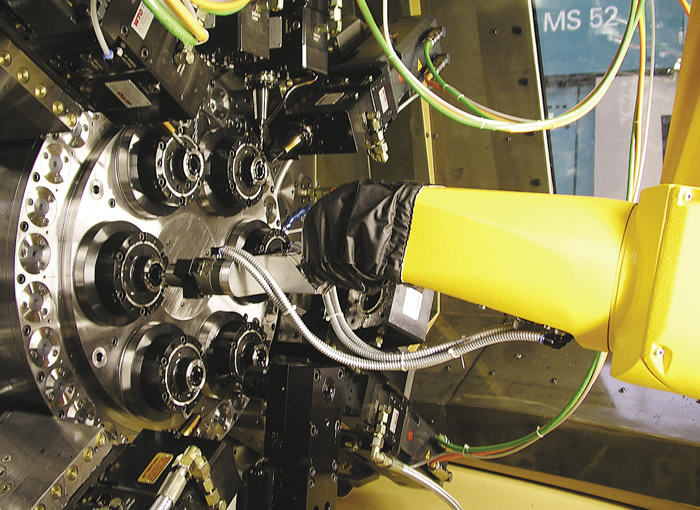

Robotic part handling increases spindle capacity and reduces floor space requirements. Image courtesy INDEX.

The multispindle national product manager for the Gildemeister line at DMG Mori USA, Hoffman Estates, Ill., Principe said he's seen renewed interest in multispindles over the past few years, especially CNC models. These machines offer fast setup times and simplified operation, and are far more flexible than their predecessors.

"Tough metals like 4140 and 52100 steel are becoming more common, while part volumes are shrinking, tolerances are getting tighter and workpieces are growing increasingly complex," Principe said. "All of these things lend themselves well to CNC multispindles."

Gildemeister still makes cam-driven multispindles, and, according to Principe, demand remains high. But where the rule of thumb for justifying a cam machine is an order of a million parts or more, CNC multispindles are often employed to cost-effectively produce a few hundred or fewer pieces.

"The longest part of setup on any multispindle machine is bar changeover, an activity that might take a few hours," he said. "If you can avoid this by standardizing on bar size or grouping jobs with like materials, setup time on a CNC machine is often a matter of changing a few tools and calling up a new program. I know a shop in Chicago that routinely does changeovers in 20 minutes or so, and most shops can do them in a couple hours or less."

All multispindles operate on a share-the-workload principle. Each spindle typically has two (or more) slides: one for end-working operations, such as drilling and boring, and the other for turning, grooving and cutoff. On a 6-spindle machine, for example, the first spindle/slide station might turn and drill, the second station might counterbore and groove and so on until the part is completed. The part cycle time is determined by the longest of the six operations, which is why it's important to level the machining load across all stations.

Counter-rotating end-working spindles increase operational spindle speeds. Image courtesy Tornos Technologies.

All those moving parts might sound scary, but Principe said programming is actually quite simple. "Anyone who knows CNC can set up one of these machines. It's a matter of programming each operation individually—face and turn on slide one, drill on slide two, tap on slide three—and the control takes care of the synchronization and makes sure that the longest operation is complete before indexing the spindles. There's no way to mess it up."

Philip Miller, managing director for North America at Tornos Technologies Corp., Lombard, Ill., agreed that multispindle setup isn't the onerous task it once was. "When I started on screw machines, I spent months just learning how to grind tools," he said. "Today, you're just buying off-the-shelf inserts and letting the CNC take care of the rest."

Tornos also makes cam-driven machines, which Miller said are ideally suited for producing "a hundred million or so" fairly simple parts. Unlike their purely mechanical predecessors, however, feed rates on these machines are controlled via a programmable logic controller, providing greater flexibility. For more complex work, there's full CNC, with AC digital servodrives and a C-axis on each of the machine's spindles.

"Chip control is key on multispindles," Miller said. "I have a customer in Wisconsin that was stopping its 8-spindle machines every few dozen parts to pull long stringers off the tools. By upgrading to a CNC machine with high-pressure coolant, they're able to machine 316 stainless around the clock with no problems."

Many shops have built successful businesses on cam-driven multispindles, Miller noted, but today's customers are typically those going after specific kinds of parts, such as aerospace components, where challenging materials and complex geometries are the norm. In this arena, only CNC will do.

Parts like these typically benefit from live-tool and Y-axis capabilities as well. Tyler Economan, applications engineering manager at INDEX Corp., Noblesville, Ind., said parts that were once dismissed as multispindle candidates are routinely machined there today. "Some CNC multispindles allow shops to mill flats and slots, drill cross-holes and perform other operations that previously required secondary operations. It's a real game changer."

Another game changer is spindle speed. Where old mechanical machines topped out at a few thousand rpm, some of today's machines boast speeds of 8,000 rpm and higher. And, by using a counter-rotating drill on an end-working station, effective spindle speeds of 15,000 rpm or more are possible.

Anyone who's stood in the middle of a screw machine shop filled with the sound of hundreds of old-fashioned "rattle tubes" might wonder at the deafening potential of these increased spindle speeds. But Economan pointed out that bar feed technology has kept up with the multispindle world. "We offer bar feeds with automatic bar-loading capabilities," he said. "These bar loaders use hydrodynamic dampening technology and, in some cases, ID pusher collets. Therefore, it is possible to utilize an ideal spindle liner closer to the actual material size, so noise and bar whip is less of an issue."