Transforming horizontal machining centers into lean, mean, part-making machines.

CNC machine shops have it rough. Customers order smaller lot sizes and demand faster turnaround than ever before. More parts are made from nasty materials like Inconel and titanium, with tolerances and geometries so challenging they make even seasoned machinists quake in their steel-toed boots. To stay profitable, many embrace lean and Six-Sigma methodologies, but keeping foreign competitors or even the shop next door at bay takes a lot more than cutting some fat from business processes. Shops must become agile if they want to compete in this brave new world of low-volume, high-complexity machining.

Agile means having the equipment, tooling, software and know-how to respond quickly to changing customer needs while still making a buck. By their very nature, horizontal machining centers are one of an agile shop’s best friends. With built-in pallet changers standard on most machines, efficient chip flow and the ability to hit all sides of a part in a single setup, horizontals increase part throughput while reducing cost compared to their vertical cousins. Add a linear pallet system or pallet pool and a large-capacity tool magazine and shops can simply leave tools and fixtures in the machine indefinitely.

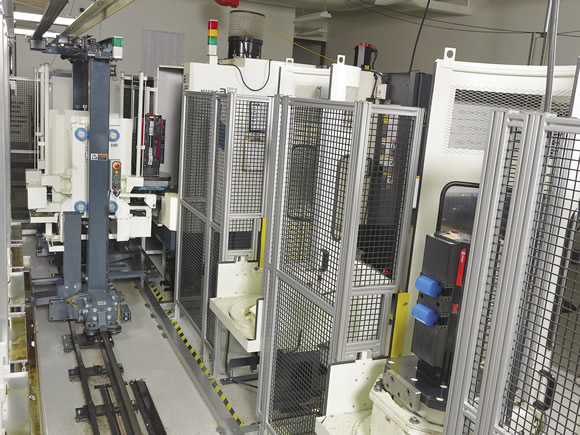

Courtesy of Makino

Precise Tool & Die, Cleveland, experienced reductions in cycle time of up to 60 percent by switching from a conventional vertical machining center to the Makino a61 horizontal machining center shown here.

This makes setup for many parts a set-it-and-forget-it affair. And, with options such as broken tool detection and automated parts handling, the transition to lights-out manufacturing becomes a reality for many shops, allowing for unattended production at night and process prove-out during the day.

A Mighty Big Spread

Of course, it takes more than equipment to become an agile shop. It takes a focused, well-managed plan and having robust processes in place to get there (see sidebar on page 43). Let’s pretend, however, that you’re already have the agility of an Olympic triathlete, having addressed the sales and quoting, purchasing, quality control and engineering processes—all key parts of being agile. It’s time to shop for a new HMC, one that will help you along the road to agile. Dave Ward, product manager for Makino Inc., Mason, Ohio, said HMCs give shops the ability to quickly respond to customer demands, while also making short runs profitable.

“There are a number of reasons for this,” Ward said. “For starters, consider the work envelope. The typical 20 "×40 " vertical is one of the most popular machining centers in the country. Those machines have roughly 800 sq. in. of space for setting up jobs. Horizontals, on the other hand, utilize a cylindrical work envelope—unwind that cylinder and you’re looking at twice the usable workspace as a typical VMC. Then consider there are two pallets on a horizontal and you have easily four times the available real estate as a comparably sized vertical.”

In addition to that large work envelope, the automatic pallet changer seen on virtually all HMCs means shops can load parts or change jobs on one pallet while the machine works on the other. This improves production efficiency and, properly leveraged, increases agility as well.

Courtesy of Methods Machine Tools

A four-station pallet pool services a pair of KIWA KH-45 horizontal machining centers.

Courtesy of Big River Engineering & Manufacturing

Big River Engineering’s linear pallet system in action.

“By taking advantage of the machining capability in a 4-axis horizontal, together with tombstone-style fixturing, shops can easily have eight jobs set up at any given time, one on each side of the tombstone,” Ward explained. “With a little planning, you can either leave those jobs in place between runs or load a new faceplate and quickly get a different job into operation. This aspect of HMCs delivers flexibility unavailable from a traditional vertical.”

Granted, VMCs can be outfitted with rotary tables and pallet changers, accomplishing much the same thing. Yet this “bolt-on” approach can’t compete against a horizontal in terms of rigidity and accuracy, two attributes necessary for agile manufacturing.

Despite the obvious advantages, Ward said shops must be careful when choosing a horizontal. “You can have the best CAM system, the best machinists, all of your tools and raw material ready to rock and roll, but if you don’t have the right machine tool, you’re very limited.”

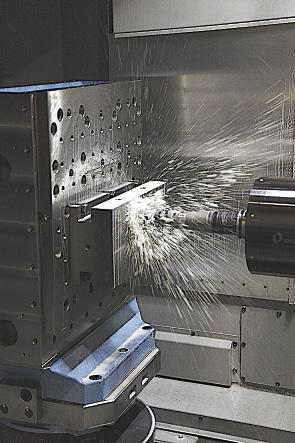

There’s a lot to consider. Ward said many machine tools stay in place for 15 years or so on average. But unless they own a crystal ball, most shops can’t predict what they’ll be doing next year or even the next day, let alone a decade from now. “Let’s say you’re running aluminum die castings today, so you select a machine with the latest 20,000-rpm spindle,” Ward said. “What happens 3 months from now when that job runs out and the next one is for cast iron parts?” For this reason, Ward said, shops should look for the best spindle technology available, preferably one with direct-drive motors, high torque and wide-ranging rpm capability. “If you’re looking to be agile and ready to handle whatever comes in the door, you really need to think ahead—prepare for the future with a horizontal machining center that is designed and built for versatility.”

Sharpest Tools in the Shed

Machine shops that operate versatile HMCs are usually in cycle 90 percent of the time, 7 days a week, which boosts their return on investment, according to David Lucius, vice president of sales for Methods Machine Tools Inc., Sudbury, Mass. There are plenty of shops adept at agile machining, but it’s a high bar to reach. “There are a couple of things working against you with high-mix, low-volume production,” Lucius said. “For one, your operators need to be very skilled.”

With lot sizes of five to 30 pieces and perhaps several dozen jobs available to run at any given time, an operator is responsible for managing multiple and, possibly, completely different parts throughout any given day. This means programming, inspection, tool offsets … the list goes on, all of it controlled by a few shop-floor Jedi knights. “The biggest challenge you have in this environment is the organization of your shop and your people,” Lucius said. “The actual machining is the easy part.”

Courtesy of Makino

Each side of the aluminum parts on this tombstone can be machined in a single cycle.

Courtesy of Choice Precision

Choice Precision uses a double-level, 12-pallet stocker station Palletech manufacturing system paired with a Mazak Variaxis 730-5X II 5-axis vertical machining center.

He suggested material flow and workholding as excellent places to begin this organization. “It’s critical for shops to develop a standardized strategy on how to fixture their parts. The ones that are best at this put a lot of thought up front into workholding flexibility and how they feed raw material.”

Another key component is pallet layout. Most shops begin their horizontal journey with a single machine, adding on a pallet pool or linear pallet system as the business grows. Lucius said: “Not every shop can write a $2 million check for a multimachine flexible machining system. But they can, perhaps, get into a nice twin-pallet horizontal with 120 tools to start. Within a year or two, they can secure an eight-pallet system or add another machine. This lets you start with a much smaller investment.”

One company that started with a multipallet solution right away is Kenlee Precision Corp., Baltimore. Kenlee selected a 6-pallet, 120 tool KIWA KH-45 HMC from Methods, giving them the ability to accommodate high-mix, low-volume manufacturing demand. Alternately, another common strategy employed by Bass Machine, also located in Baltimore, was to purchase a pair of KIWA KH-45 HMCs—one with 60 tools and the other expandable to 120 tools.

The caveat is to make certain that adding capability doesn’t throw production into the tank. “Integrating multiple machines after the fact can easily cost several weeks of downtime,” Lucius said. “Buying modular equipment, with in-the-field expandable tool and pallet technology, helps alleviate this disruption.”

In Bass Machine’s case, this means they can have more tools or pallets on their KIWAs within 1 week, minimizing any negative impact on production.

One and Done

Another company that’s done just that is Choice Precision Inc., Whitehall, Pa. With a shop full of modern CNC equipment, including Mazak Palletech Manufacturing Systems equipped with pallet stackers and large-capacity tool magazines, Choice is one of the shops helping to define agile manufacturing. President Beth Rothwell agreed that winning at this game takes far more than high-tech equipment. “You can’t just buy a few horizontals and expect to be successful. Achieving this level of flexibility requires a cultural change: shop organization, employee education, tooling and fixturing—all of the elements have to be considered.”

Courtesy of Choice Precision

The Mazak Integrex i-200S multitask machine at Choice Precision flexibly and efficiently processes parts.

Rothwell pointed out that Choice is presented with thousands of different parts each year, each with unique requirements. “Our team works together to determine the right work center for the part to be machined on, the correct sequence of operations, how the part’s going to be held and what tools will cut it.”

She added there’s no general recipe for managing the process because it is part specific. But by developing the right work environment and the best employees and providing them with flexible equipment and tools, the shop is able to respond quickly to customer needs.

“The Palletech systems are a central part of the equation,” Rothwell said. Choice has two Palletechs on HMCs and one on a 5-axis VMC. “I will say, however, that our 5-axis machining centers and multitasking CNC turning centers are equally important. As our customers continue to design more complexity into their products, we can provide better quality and quicker turnaround if we’re not transferring parts from machine to machine. We try to grip it once and get everything done in as few operations as possible. High-tech machines such as these lend themselves very well to that approach.”

Go Big or Go Home

Tom Roehm, CEO of Big River Engineering & Manufacturing LLC, Memphis, Tenn., said HMCs make good sense. Starting with a single Makino machine 3 years ago, the shop has since added a six-pallet linear Makino Machining Complex (MMC) pallet system. “We machine a lot of medical instruments and components, in 20- to 50-piece quantities. Most of our parts are clamped with quick-change snap jaws, and we use touch probes for positioning. That’s one of the ways we reduce setup time. It also lets us run completely lights-out.”

Big River has also written proprietary macro programs. Between in-process probing, redundant tools and high- density workholding, some pallets run 14 hours or more unattended. “When we first started thinking about lights- out, it was always talked about with respect to Swiss machines,” Roehm said. “But we’ve made lights-out on our horizontal a reality. By writing special programs, we can do a whole lot of probing at night. We check every part, after every operation. If a tool wears, we’ll go get a replacement or just grab a different pallet if there was a pileup. You might spend a little more time probing this way, but at the end of the day you’re winning the race.”

By merging lean concepts with flexible, high-performance machining centers, shops can respond quickly and profitably to customer demands, while reducing production quantities and profit margins to levels once considered ridiculous. Single-piece flow, the holy grail of agile, is within the reach of many shops. All it takes is the right investment in people, tools and machines, a long, hard look at your business processes and a lot of hard work. CTE

Shops be nimble, shops be quick …

While having the right equipment is essential for machine shops to implement agile manufacturing, so is having the right administrative and management systems. “Being agile is the ability to quickly meet the changing demands of your clients, and do so with competitive pricing and high quality,” said Larry Coté, founder of Lean Advisors Inc., Ottawa, Ontario. “Before making a huge investment in capital equipment, however, people definitely need to understand that the machine is only one point in the flow of servicing your client.”

To illustrate his point, Coté described a scenario where a company just bought the biggest, fastest piece of equipment available. “What do you think the sales guy is going to do once he has the purchase order in hand? He’s going to sell the same machine to the competition. To be a leader in today’s market requires much more than technology; it requires an analysis of the entire end-to-end manufacturing process.”

Say Joe’s Machine Emporium just bought a shiny new HMC. It’s a beautiful piece of equipment and cranks out parts much faster than the machines at Joe’s nearest competitor, Hank’s Precision Machining. Yet Joe takes a couple of weeks to quote a job, while Hank returns quotes in a day or two. Hank’s shop is ISO-certified and has a Web site where customers can view job status and track design changes, whereas Joe doesn’t even have a Web site and couldn’t spell ISO if his life depended on it.

Hank’s has offline toolsetting, quick-change tooling and a crib stocked with high-quality cutters and holders. His employees are motivated by decent wages, profit sharing and continuous improvement bonuses, not to mention the pride of working for a company that “does it right.” On the tail end, Hank has electronic billing and shipment notifications to speed up the payables and receivables process. Joe, on the other hand, has none of these, relying instead on better machines to compete. Granted, Hank takes longer to machine parts. He’s not the cheapest either. Yet Hank’s customer service, internal processes and employee morale blow Joe out of the water. Who do you think will win more business?

By streamlining their business activities before purchasing new equipment, Coté said shops can realize significantly better return on investment. The alternative is potential financial disaster. “One way or another, the bank has to be paid,” he said. “Without working on the downstream and upstream processes that surround any machine tool, there is no competitive advantage to be gained by investing in one. Ultimately, those companies that try to keep up through equipment alone end up in bankruptcy.”

This begins with the client’s initial contact and concludes with delivery and invoicing. “This combination of systematic thinking and technical advantage can’t be bought or easily duplicated by the competition,” Coté said. “Shops must pay attention to the entire process, assessing every activity and optimizing wherever possible to ensure that everything they do provides value to their customers.”

—K. Hanson

Contributors

Big River Engineering & Manufacturing LLC

(901) 382-0609

www.bigrivermemphis.com

Choice Precision Inc.

(610) 502-1111

www.choiceprecision.com

Lean Advisors Inc.

(877) 778-6413

www.leanadvisors.com

Makino Inc.

(888) 625-4664

www.makino.com

Methods Machine Tools Inc.

(877) MMT-4CNC

www.methodsmachine.com

Related Glossary Terms

- centers

centers

Cone-shaped pins that support a workpiece by one or two ends during machining. The centers fit into holes drilled in the workpiece ends. Centers that turn with the workpiece are called “live” centers; those that do not are called “dead” centers.

- computer numerical control ( CNC)

computer numerical control ( CNC)

Microprocessor-based controller dedicated to a machine tool that permits the creation or modification of parts. Programmed numerical control activates the machine’s servos and spindle drives and controls the various machining operations. See DNC, direct numerical control; NC, numerical control.

- computer-aided manufacturing ( CAM)

computer-aided manufacturing ( CAM)

Use of computers to control machining and manufacturing processes.

- feed

feed

Rate of change of position of the tool as a whole, relative to the workpiece while cutting.

- fixture

fixture

Device, often made in-house, that holds a specific workpiece. See jig; modular fixturing.

- machining center

machining center

CNC machine tool capable of drilling, reaming, tapping, milling and boring. Normally comes with an automatic toolchanger. See automatic toolchanger.

- precision machining ( precision measurement)

precision machining ( precision measurement)

Machining and measuring to exacting standards. Four basic considerations are: dimensions, or geometrical characteristics such as lengths, angles and diameters of which the sizes are numerically specified; limits, or the maximum and minimum sizes permissible for a specified dimension; tolerances, or the total permissible variations in size; and allowances, or the prescribed differences in dimensions between mating parts.

- quality assurance ( quality control)

quality assurance ( quality control)

Terms denoting a formal program for monitoring product quality. The denotations are the same, but QC typically connotes a more traditional postmachining inspection system, while QA implies a more comprehensive approach, with emphasis on “total quality,” broad quality principles, statistical process control and other statistical methods.

- turning

turning

Workpiece is held in a chuck, mounted on a face plate or secured between centers and rotated while a cutting tool, normally a single-point tool, is fed into it along its periphery or across its end or face. Takes the form of straight turning (cutting along the periphery of the workpiece); taper turning (creating a taper); step turning (turning different-size diameters on the same work); chamfering (beveling an edge or shoulder); facing (cutting on an end); turning threads (usually external but can be internal); roughing (high-volume metal removal); and finishing (final light cuts). Performed on lathes, turning centers, chucking machines, automatic screw machines and similar machines.

- web

web

On a rotating tool, the portion of the tool body that joins the lands. Web is thicker at the shank end, relative to the point end, providing maximum torsional strength.

- work envelope

work envelope

Cube, sphere, cylinder or other physical space within which the cutting tool is capable of reaching.