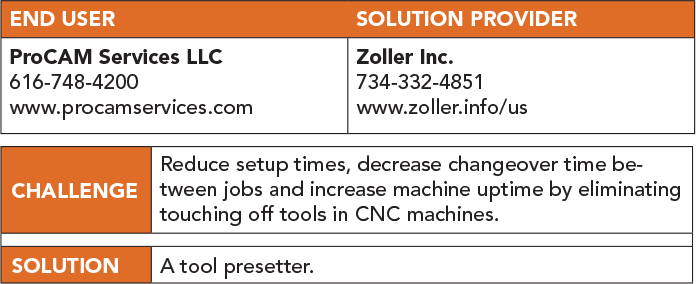

Poll any group of machine shop owners and chances are every one of them wants to reduce setup times, decrease changeover time between jobs and increase machine tool uptime. But ask them about the technology they use to be more efficient, and their responses will likely reveal a range of approaches.

Even so, as the manufacturing industry’s persistent skilled worker shortage drives interest in productivity-boosting solutions, smalland medium-sized job shops are increasingly recognizing the time and money they can save with tool presetters. These offline machines measure various dimensions of cutting tools, including length, diameter and offsets, before the tools are installed in a machine tool.

Alex Bassett (left), day shift foreman, and Tom Bassett II, owner, with ProCAM Services’ Zoller »smile 420« tool presetter. Zoller

Alex Bassett (left), day shift foreman, and Tom Bassett II, owner, with ProCAM Services’ Zoller »smile 420« tool presetter. Zoller

Job shop owners frequently have the misconception that presetters are not for them, according to Dietmar Moll, director of sales at Zoller Inc., an Ann Arbor, Michigan-based company that provides manufacturing hardware and software, including presetters. "But often when we get the presetter into their shop and they see the results, their only complaint is they wish they had purchased one sooner."

That’s what happened at Pro-CAM Services LLC, a family-owned CNC machine shop that Tom Bassett II established nearly 30 years ago. Initially skeptical of tool presetters, Bassett’s reservations vanished after he purchased the Zoller »smile 420« about five years ago and incorporated the presetter into the workflow of his busy shop in Zeeland, Michigan.

Zoller reports that its internal tests show measuring with a tool presetter is at least 45% faster than with the machine tool’s internal control. Setting up jobs on the presetter also freed up time Pro- CAM machinists previously spent touching off tools in the shop’s CNC machines. This streamlined approach where a machinist measured tools for one job while the machine cycled through another job allowed ProCAM to accept more orders.

In the company’s first year using the tool presetter in 2019, sales increased by $300,000, and then grew by another $700,000 the next year. Bassett said he attributes the bulk of that $1 million increase to more efficient processes that improved the productivity of all the shop’s machine tools. "I don’t think I’ve ever had a piece of equipment that I’ve gotten in the shop that changed things so much."

Bassett said he believed presetters didn’t belong in shops like Pro- CAM with its high mix and low volume of orders and frequent job changes. ProCAM positions itself as an agile job shop that beats its competitors on lead time without sacrificing quality. Each of the company’s machinists often cycle through 20 to 30 tools a day to fulfill orders.

The 3,530-sq.-m (38,000-sq.-ft.) shop includes eight milling machines — vertical and horizontal mills and three-, four- and five-axis mills — three lathes, including one six-axis unit, and two CNC routers.

"We’ve had customers call in the morning and say, ‘Hey, we’re broken down. We need this,’ and then we’ve delivered the part to them in the afternoon," Bassett said. "It doesn’t always go that way, but most of the time, our backlog is about two weeks because we cycle through things so fast."

Bassett said he was intrigued by a demo of the »smile 420« at a trade show and then calculated how much time his machinists spent touching off tools and checking runout in a machine tool before production. He realized they spent from 30 minutes to an hour per job on setup. When multiplied by the number of jobs per machine tool each day — and then extended over weeks, months and years — the numbers were alarming. Applying the shop’s hourly machining rate to those numbers brought the lost opportunity cost into focus.

The dimensions of a drill are measured in the »smile 420« tool presetter at ProCAM Services. Zoller

The dimensions of a drill are measured in the »smile 420« tool presetter at ProCAM Services. Zoller

After running the numbers, Bas-sett said, "There’s just no way this is right. I’m going from, ‘This thing isn’t something for our shop,’ to ‘Oh my God, I got to have this thing.’"

Today, presetting tools on the »smile 420« is the first step of Pro-CAM’s machining processes once an order reaches the shop floor, he noted. Outside of the considerable time savings, the presetter introduced a level of repeatability that human operators simply cannot replicate. The machine’s high-precision SK-50 spindle, optics and image processing camera reportedly provide accurate data each time for a consistent operation.

"Before the Zoller equipment, with the touch offs, you had a wide range of variables from one person to the next," Bassett said. "Day shift starts the project, night shift comes in, and now you’ve got two different touch-off techniques, and they’re off a little bit here and there. Then you can end up with quality issues with the parts or have to rerun programs again to get the blends right. With the Zoller equipment, that doesn’t happen anymore because everybody’s touch offs are exactly the same."

The presetter can output data automatically to the machine, eliminating the possibility of data entry errors. Bassett took this further by internally developing a program that outputs the data to multiple machine tools so machinists can pull up the values on any machine.

While Bassett was sold on the math behind a tool presetter’s value, he knew a major hurdle was convincing his machinists. Previously, ProCAM machinists measured tools in the machine tool prior to production through a variety of methods.

"Each machinist has their own little technique where they come down on the surface, and they’re using shim stock or some use 1-2-3 blocks and they’re sitting there, working the thing in," he said. "If they’re checking runout on that tool, it can take them anywhere from a minute to five minutes to do one tool. It would be no problem for a job to have 15 tools in it, so there goes anywhere from 15 minutes to 45 minutes just loading tools in the machine. With Zoller, you’re done in less than five minutes."

Seeing is believing, so when one ProCAM machinist doubled down that his technique was superior, Bassett said he posed a challenge: Touch off your tools the old way and compare the results to the tool presetter. "And in less than a week, he was no longer touching off his own tools."

Alex Bassett, the day shift foreman and Tom’s youngest son, said the machinists now trust the presetter completely. "It just gives us less to worry about. When you’re setting up complicated stuff, there are times where your mind is melting because you’re like, I got to check this, check this, check this. But at the end of the day, I got the Zoller, I know this tool, that’s one less thing to worry about. It gives you peace of mind."

Contact Details

Related Glossary Terms

- arbor

arbor

Shaft used for rotary support in machining applications. In grinding, the spindle for mounting the wheel; in milling and other cutting operations, the shaft for mounting the cutter.

- computer numerical control ( CNC)

computer numerical control ( CNC)

Microprocessor-based controller dedicated to a machine tool that permits the creation or modification of parts. Programmed numerical control activates the machine’s servos and spindle drives and controls the various machining operations. See DNC, direct numerical control; NC, numerical control.

- computer-aided manufacturing ( CAM)

computer-aided manufacturing ( CAM)

Use of computers to control machining and manufacturing processes.

- gang cutting ( milling)

gang cutting ( milling)

Machining with several cutters mounted on a single arbor, generally for simultaneous cutting.

- milling

milling

Machining operation in which metal or other material is removed by applying power to a rotating cutter. In vertical milling, the cutting tool is mounted vertically on the spindle. In horizontal milling, the cutting tool is mounted horizontally, either directly on the spindle or on an arbor. Horizontal milling is further broken down into conventional milling, where the cutter rotates opposite the direction of feed, or “up” into the workpiece; and climb milling, where the cutter rotates in the direction of feed, or “down” into the workpiece. Milling operations include plane or surface milling, endmilling, facemilling, angle milling, form milling and profiling.