Dry Out

Dry Out

As the government publishes ever-stricter regulations for metalworking fluids, more shops try dry machining. The author examines the cost benefits of machining dry and looks at the various types of tool materials designed to enhance dry-machining applications.

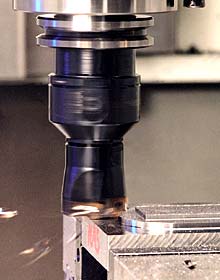

Machining dry eliminates the costs and hassles of using fluids.

Machining dry should be "standard operating procedure" for many metalcutting jobs. It's not only possible to turn hardened materials dry, it's profitable.

Just two decades ago, cutting fluids accounted for less than 3 percent of the cost of most machining processes. Fluids were so cheap that few machine shops gave them much thought. Times have changed, though.

Today, cutting fluids account for up to 15 percent of a shop's production costs, and machine shop owners constantly worry about fluids.

Cutting fluids, especially those containing oil, have become a huge liability. Not only does the Environmental Protection Agency regulate the disposal of such mixtures, but many states and localities also have classified them as hazardous wastes and impose even stricter controls if they contain oil and certain alloys.

Because many high-speed machining operations and fluid nozzles create airborne mists, governmental bodies also limit the amount of cutting fluid mist allowed in the air. Moreover, the EPA has proposed even stricter standards for controlling such airborne particulate. And the Occupational Safety and Health Administration is considering an advisory committee's recommendation to lower the permissible exposure limit to fluid mist.

The costs of maintenance, recordkeeping and compliance with current and proposed regulations is rapidly boosting the price of cutting fluids. Consequently, many machine shops are considering eliminating the costs and headaches associated with cutting fluids altogether by cutting dry.

Many shops that would like to cut dry, though, are unsure that they can. They believe that cutting fluids are necessary to reach higher speeds and to cut the harder materials that they must use to stay competitive. Many also believe that the cost of changing a wet operation to a dry one would be too high.

Neither is true. Machining dry should be "standard operating procedure" for many metalcutting jobs. It's not only possible to turn hardened materials dry and mill dry at high speeds, it's profitable. The trick is to know how to correctly integrate the tools, machines and cutting techniques.

'Convention' Behind Fluid Use

A major impediment to the growth of dry cutting is the conventional wisdom that metalworking fluids are necessary to attain acceptable finishes and long tool life. Although fluids are needed for many applications, research shows that this isn't always the case with today's cutting tool materials. Advanced grades of cemented carbide, especially those protected with a coating, cut more efficiently without cutting fluids when run at high speeds and temperatures. In fact, with interrupted cutting, the hotter the cutting zone, the more unsuitable a fluid is.

Consider a milling operation. Assuming that the fluid can overcome the centrifugal forces created by a milling cutter rotating at high speeds, the fluid vaporizes well before reaching the cutting zone, so it produces little or no cooling effect anyway. As a result, temperature fluctuations are greater when fluid is applied. A milling insert cools when it exits the cut. It heats up again when it re-enters the workpiece. Although the heating and cooling cycle occurs in dry machining, the temperature fluctuations are much greater when cutting fluid is present. The ensuing thermal shock can create stress in the insert and crack it prematurely.

A similar situation can arise during production turning. When cutting medium-carbon steel at speeds higher than 130 m/min., for example, uncoated carbide inserts engaged in the cut for less than 40 seconds can suffer pronounced thermal shock when exposed to coolant. This shock shortens tool life drastically by increasing crater wear slightly and flank wear significantly. Since the time in cut for most production turning is less than 40 seconds, cutting dry often extends tool life.

Drilling, however, is another matter. Cutting fluids are often necessary while drilling because they provide lubrication and flush chips from the hole. Without fluids, chips can bind in the hole, and the surface roughness average (Ra) can be twice as high as when drilling wet. Cutting fluids also can reduce the required machine torque by lubricating the point at which the drill margin touches the hole's wall.

Although coated drills can duplicate the lubricating effect of fluids somewhat, the coatings that reduce cutting forces the most tend to offer the least abrasion-resistance.

The decision to cut wet or dry must be made on a case-by-case basis. A lubricious fluid often will prove beneficial in low-speed jobs, hard-to-machine materials, difficult applications and when surface-finish requirements are demanding. A fluid with a high cooling capacity can enhance performance in high-speed jobs, easy-to-machine materials, simple operations, and jobs prone to edge-buildup problems or having tight dimensional tolerances.

Many times, though, the extra performance capabilities that a cutting fluid offers is not worth the extra expense incurred. And in a growing number of applications, cutting fluids are simply unnecessary or downright detrimental. Modern cutting tools can run hotter than their predecessors and, sometimes, compressed air can be used to carry hot chips away from the cutting zone.

Coatings Manage Heat

In milling, cutting-zone temperatures fluctuate more when cutting fluid is used than when the operation is run dry. Large temperature fluctuations can create stress in the tool and crack it prematurely.

Coatings are a big part of the reason that cutting fluids are often unnecessary today. They control temperature fluctuations by inhibiting heat transfer from the cutting zone to the insert or tool. The coating acts as a heat barrier, because it has a much lower thermal conductivity than the tool substrate and the workpiece material. Coated inserts and tools, therefore, absorb less heat and can tolerate higher cutting temperatures, permitting the use of more aggressive cutting parameters in both turning and milling without sacrificing tool life.

Coating thickness is between 2 and 18 microns and plays an important role in a tool's performance. Thinner coatings can better withstand the temperature fluctuations that arise during interrupted cuts than thicker coatings. The reason is because thinner coatings incur less stress, making them less likely to crack. During rapid cooling and heating, thick coatings experience what glass does when you heat or cool it too quickly. Running thinly coated inserts dry can extend tool life by up to 40 percent.

This is a big reason why the physical-vapor-deposition process typically is used to coat round tools and milling inserts. PVD coatings tend to be thinner than their chemical-vapor-deposition counterparts, and they adhere better to contours. In addition, PVD coatings can be deposited on carbide at much lower temperatures, so they find more use on the up-sharp edges and highly positive geometries of milling and turning tools.

Although titanium nitride is utilized for 80 percent of all coated tools, titanium aluminum nitride has emerged as the best PVD coating for cutting dry at high speeds. TiAlN can outperform TiN by as much as 4-to-1 in continuous, high-temperature cuts, such as those made during high-speed turning. TiAlN also excels in situations that involve high thermal stress, like dry milling and deep-hole drilling of small-diameter holes that cutting fluids have a difficult time penetrating.

TiAlN is harder than TiN at cutting temperatures and is the most thermally stable and chemically wear-resistant PVD coating available. Its hardness is as high as 3,500 Vickers, and its working temperature is as high as 1,470° F. Materials scientists suspect that these properties are attributable to an amorphous aluminum-oxide film that forms at the chip/tool interface when some of the aluminum at the coating surface oxidizes at high temperatures.

Research is under way to apply ultrathin, multilayer PVD coatings. Such deposition processes build a coating made of hundreds of layers that are only a few nanometers thick. In contrast, conventional PVD processes deposit several layers of micron-thick coatings.

Despite intense interest in PVD coatings, their CVD counterparts continue to be more popular for the machining of most ferrous materials. The higher deposition temperatures in CVD processes aid adhesion and allow higher cobalt concentrations in the substrate, which toughens the edges and helps the body resist deformation. Because CVD coatings tend to be thicker than PVD coatings, they require heavier hones on their cutting edge to prevent the coating from chipping—similar to how a thick layer of paint on the corner of a wall tends to chip. This design element also helps the tool resist abrasion wear and allows running at feeds up to 0.035 ipr.

CVD also is the only process that can deposit a usable layer of aluminum oxide, the most heat- and oxidation-resistant coating known. Aluminum oxide is a poor conductor that insulates the tool from the heat generated during chip formation. It forces heat to flow into the chip, making it an excellent CVD coating for most dry turning performed with carbide tools. It also protects the substrate at high cutting speeds and is the best coating for resisting both abrasive and crater wear.

Some Like It Dry

Developments in coating technology have spurred the growth of dry machining. Shown is Carboloy's TX 150 turning grade, which combines a substrate designed for cast irons and a coating applied by the medium-temperature CVD process.

Although coated grades have better tool life and are more reliable in dry milling operations than in wet ones, the demand for faster cutting speeds is pushing cutting temperatures beyond the economical limits of carbide tools. Dry machining cast iron at 14,000 rpm and 1,575 ipm, for example, can heat the cutting zone in front of the tool to temperatures between 600° and 700° C. Metal-removal rates are similar to those seen while milling aluminum with more conventional techniques, but the temperature generated in cast iron is too high for conventional cutting tools.

As a consequence, the higher cutting speeds will require more wear-resistant cutting tool materials, ones that possess higher hot hardness. Cermet, cubic boron nitride and two ceramics—aluminum oxide and silicon nitride—fit the bill nicely. (Today, the term "ceramics" includes both aluminum oxide and silicon nitride, not just aluminum oxide as it did in the past.) Although not recommended for ferrous materials, polycrystalline diamond is another tool material that performs well in dry conditions. In all these materials, however, the tradeoff for their greater hot hardness and abrasion resistance is brittleness.

The advantages of each material are presented below.

-

Cermet: an advanced carbide. Cermet can run hotter than conventional carbide, but it lacks carbide's shock resistance, toughness at medium-to-heavy loads, and strength at low cutting speeds and high feeds. Cermet has roughly the same edge strength as conventional carbide at small, constant loads; tends to withstand temperature and abrasion at high cutting speeds better; lasts longer; and imparts finer finishes. It also is better at resisting built-up edge and imparting good finishes when used on ductile and sticky materials.

The better hot hardness comes from the titanium compounds that make up the material. Cermet is a type of cemented carbide containing hard, titanium-based compounds (titanium carbide, titanium carbonitride and titanium nitride) in a nickel or nickel-molybdenum binder. Because of the metallic binder's temperature limitation, cermet grades typically do not have a high enough hot hardness to machine materials above Rc 40.

Cermet also is more sensitive to fracture and feed-induced stress than coated and uncoated carbides. Therefore, it performs best in jobs requiring high accuracy and a fine finish. Ideal machining operations are those that don't involve severe interruptions in the cut.

The feed limit for turning carbon steel is usually 0.025 ipr, and general-purpose milling can proceed at moderate feeds and high spindle speeds. If kept within these operating limits, cermet can retain a sharp cutting edge for a long time in high-volume jobs. Although cermet can pay for itself at conventional speeds and feeds simply by improving on the wear life and finish provided by a carbide tool, it also can boost productivity by cutting up to 20 percent faster in alloy steels and up to 50 percent faster in carbon steels, stainless steels and ductile irons.

- Ceramic: a family of materials. Ceramic cutting tools are similar to their cermet counterparts in that they are more chemically stable than carbide, last a long time and can machine at high cutting speeds. Pure aluminum oxide has extremely high thermal resistance but low strength and toughness, which means that it fractures easily if conditions are not optimal.

To make it less sensitive to cracking, cutting tool manufacturers add either zirconium oxide, to improve toughness, or a mixture of titanium carbide and titanium nitride, to boost shock resistance. Despite these additions, though, ceramic's toughness is still much less than that of cemented carbide.

Another method for enhancing the toughness of aluminum oxide is to implant crystalline veins, or whiskers, of silicon carbide into the material. Although these whiskers typically average only 1 micron in diameter by 20 microns long, they are very strong and increase toughness, strength and thermal-shock resistance considerably. Whiskers can constitute up to 30 percent of the material.

Like aluminum oxide, silicon nitride has a higher hot hardness than carbide. It also withstands thermal and mechanical shocks better. Its main drawback compared to aluminum oxide is that its chemical stability isn't as good when machining steel. However, silicon nitride machines gray cast iron at 1,450 sfm and higher.

Although the mrr can be high with a ceramic tool, the application must be right. For example, ceramic tools don't work well in aluminum, but they excel in gray and nodular cast iron, hardened and some unhardened steels, and heat-resistant alloys. Even in these materials, though, success depends on the edge preparation, presentation of the tool to the work, the stability of the machine and setup, and utilizing the optimal machining parameters.

- CBN: hardness second to diamond. CBN is an extremely hard cutting tool material. It usually works best in materials harder than Rc 48. It has excellent hot hardness—up to 2,000° C. Although more brittle than carbide and less thermally and chemically stable than ceramic, it has higher impact strength and fracture resistance than ceramic tools. It also requires a less rigid machine to cut hardened metal. Moreover, properly tailored CBN tools can withstand the chip loads of high-power roughing, the pounding of interrupted cuts, and the heat and abrasion of fine finishing.

Proper tailoring for demanding jobs involves making sure that the machine and setup are rigid, edge preparations are large enough to prevent microscopic chipping and the tool substrate has a high CBN content. This allows the tool to operate at high speeds, with heavy mechanical edge loading and in severely interrupted cuts. These properties make such grades the tool material of choice for roughing hardened steel and pearlitic gray cast iron.

A tool with a low CBN content is more brittle, but it is better for hardened ferrous alloys. With a lower thermal conductivity and a higher compressive strength, CBN withstands the heat generated from high cutting speeds and negative rakes. Higher temperatures in the cutting zone soften the work material and aid chip separation. The negative geometry strengthens the tool, stabilizes the cutting edge, improves tool life and allows DOCs shallower than 0.010".

Because CBN tools can leave surface finishes finer than 16µin. and hold ±0.0005" accuracies when ganged, dry turning hardened workpieces is often an attractive alternative to messy, coolant-intensive grinding operations. CBN is a favorite tool material for hard turning and high-speed milling, but the ranges of applications for ceramic and CBN overlap tremendously, so cost-benefit analyses are typically necessary to determine which will offer the best results.

- PCD: excels in nonferrous work. As the hardest cutting tool material available, polycrystalline diamond is the best at withstanding abrasive wear. Its hardness and wear-resistance comes from the random crystal orientation and diamond-to-diamond bonding that inhibit crack propagation. Attaching PCD tips to cemented carbide inserts adds strength and shock resistance and can lengthen carbide tool life by up to 100 times.

Other properties, however, preclude its use for most machining operations. One is the affinity that PCD has for the iron in ferrous metals. The resulting chemical reaction limits this tool material to nonferrous applications. Another limiting property is its inability to withstand cutting-zone temperatures exceeding 600° C. Consequently, PCD cannot cut tough, high-tensile materials.

Nevertheless, PCD works well on nonferrous materials, particularly abrasive, high-silicon-content aluminum. Sharp cutting edges and highly positive rakes are essential to shear such materials efficiently and minimize cutting pressure and BUE.

Strengthen the Edge

Despite recent physical improvements and application developments, tools made from cermet, ceramics, CBN and PCD are still more brittle than carbide and cannot withstand as much stress. As a result, tools made from these materials must incorporate design features that add support and relieve stress.

It's important, for example, to grind the cutting edge so that it redirects the cutting forces away from the insert's edge and into its body. Three such edge preparations are appropriate: T-land, hone and honed T-land.

The T-land, a chamfer-like flat at the edge, replaces a weaker sharp point. The tool designer's goal here is to find the minimum land width and angle that give the edge adequate strength and life; large widths and angles strengthen the insert but also increase cutting forces.

Hones are rounded-off sharp edges. Although they do not offer the same protection against chipping as T-lands, hones work well on advanced-material inserts used for finishing operations. These inserts must be run at shallow DOCs and low feed rates to keep cutting pressure to a minimum.

Hones also can strengthen T-lands when applied to the points at which the land intersects the rake and flank surfaces. When minute chipping occurs in applications such as the rough turning of steel with ceramics, hones can relieve stress at these points, strengthening the insert without having to make the land larger.

Besides specifying the best edge preparation for the job, the tool designer also must optimize the tool's cutting geometry and ability to eject chips. Reducing cutting forces by widening the clearance angle puts less stress on the tool and lowers the temperature in the cutting zone. Rake angles that are as positive as possible also reduce cutting forces by creating a better shearing action, and wide-flute gullets aid chip evacuation by providing a large exit path, especially in drilling and threading.

Another way to keep tangential cutting forces low is to cut at high speeds. A high feed rate at very high spindle speeds reduces, rather than increases, the thrust against the workpiece by as much as 75 to 90 percent, depending on the tool and machining parameters. Moreover, milling cutters are more accurate than they were five years ago, and milling and turning machines have become more mechanically stable and rigid, thereby eliminating undue vibration. All of these developments support the use of brittle—but harder and more wear-resistant—cutting tool materials.

One of the benefits of using a tool that can withstand high temperatures is that chip formation can be extremely efficient. In cast iron, for example, the heat plasticizes the material in the cutting zone and lowers its yield strength. The result is a threefold increase in metal-removal efficiency, compared to conventional roughing. Because the feed rate is high, the tool shears the material so fast that most of the heat stays in the chip and does not have time to flow into the workpiece and distort it. Despite the higher cutting temperatures, the workpiece has more thermal stability and is more accurate than if it were cut at conventional removal rates.

Low-thrust finishing also minimizes static deformation of the workpiece, fixture and machine. Such an operation calls for utilizing low-density cutters with fewer inserts run at a low feed and high surface footage. Because less clamping forces are needed to hold the workpiece, fixtures can be simple. This gives the cutting tool greater access to a prismatic part.

Machine Considerations

When machining dry, it's important to specify the right machine and outfit it correctly. Because speeds are typically faster, materials are often harder and cutting temperatures are much higher when machining dry, the machines must be rigid and powerful.

Before cutting dry on machining centers, users should strive to keep their tools short, make sure that their spindles are inherently rigid, and consider the machine's speed and power ratings.

With respect to lathes cutting near-net shapes and hardened parts, tool turrets can work against the machines' rigidity by creating a long path for resolving the cutting forces. A well-designed machine will resolve those forces along short, direct paths and will contain as few machine elements as possible to move and support the tool. After weighing accuracy against flexibility, you might consider bolting gang tools directly to the cross-slide to eliminate the rotary indexing mechanism.

Thermal stability is critical for accuracy, too. Some builders enhance the mechanics of their machining centers with software that compensates for thermal growth. Controlling temperature variation, however, should start with evacuating hot chips efficiently, thereby eliminating an important heat source inside the work envelope.

A well-designed machine doesn't have pockets or plateaus where chips can accumulate. A good design incorporates augers and chip conveyors that move dry chips out of the machine without assistance from a cutting fluid. If chips become a problem, try using air instead of a fluid.

Telescoping covers, enclosures, seals and dust collectors are also required to protect the ballscrews, ways and operator from any dust that might become airborne. Although converting a machine designed for wet operations into a dry-cutting machine is possible, it's usually cheaper and less problematic to buy one tailored for dry cutting. Its dust collector and compressed-air-delivery system are generally less expensive than the mist collector and coolant pump on a corresponding wet operation.

Operating costs are also lower with dry machining because it eliminates coolant management and disposal costs and because air compressors consume less electricity than coolant pumps.

All of these factors—along with relief from the myriad of existing cutting fluid regulations—heighten the appeal of "drying out" for those in the metalcutting industry.

About the Author

Don Graham is the manager of turning programs at Carboloy Inc., Warren, Mich.