Embracing slot diversity

Embracing slot diversity

Various tools and techniques can maximize productivity when slot milling.n

Regardless of whether an end user plows a cutting tool into a workpiece material or takes small, light and fast cuts, slot milling can be hard, depending on the application.

"Taking a 3"-dia. (76.2 mm) cutter and burying it in titanium is pretty challenging," said Luke Pollock, product manager for Walter USA LLC in Waukesha, Wisconsin. "Anything that is difficult to machine, like stainless steel, or where chip control is a big concern is always going to be a challenge."

Effective chip evacuation is also a consideration when milling a deep slot or groove because re-cutting chips shortens tool life and chips can mar the surface finish, said Joseph DeRoss, Eastern U.S. milling specialist for Sandvik Coromant Co. in Fair Lawn, New Jersey. According to Dan Tucker, Western U.S. milling specialist, a slot is deep when a tool takes a cut at least two diameters deep. (Both men support the Central U.S.)

"As far as deep grooves," Tucker said, "where you are going to have chip evacuation issues, horizontal machines are the preferred method."

Because of how parts usually are positioned for slotting, Greg Bronson, sales director of the Americas for Saegertown, Pennsylvania-based Greenleaf Corp., said most large-diameter slotting is performed on horizontal machining centers while many T-slot cutters and undercut tools are applied vertically.

He added curved slot milling to the list of challenges. End users that serve the aerospace or power generation industries perform that operation when producing bladed disks, or blisks, where the shape of the airfoil is curved.

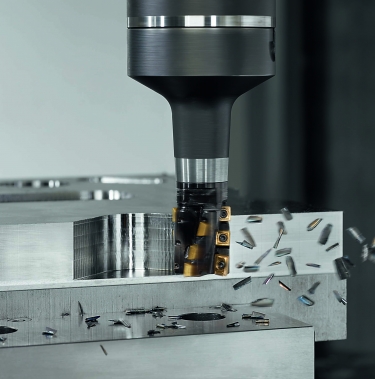

Walter USA offers a variety of tools for slot milling, including porcupine cutters. Image courtesy of Walter USA

Bronson said Greenleaf designs cutters that go into curved shapes, "which is a challenge because you don't have a straight line of sight through that slot like you would with traditional slotting. The tool is a little unusual. When you look at the side profile of a contact lens, it's dished; that's the shape of the cutter."

Unlike most cutting tool manufacturers, he said 60% to 70% of the tools Greenleaf sells for slot milling are specials because the standard line from the company is fairly narrow.

"We do a lot of custom work for customers based on what their specific part needs are," Bronson said.

For example, the toolmaker has produced slot mills with diameters as large as 660.4 mm (26").

When a blade is attached to a disk rather than being integral like a blisk, a connection that looks like a fir tree is needed, Bronson said. The feature frequently is rough- and finish-broached, but Greenleaf produces milling tools that can eliminate the need to rough-broach the slot, significantly reducing cycle time.

Tool Time

Because slots or grooves can be short or long, closed or open, straight or crooked, deep or shallow and wide or narrow, one type of tool does not suit all applications, according to Sandvik Coromant. Options include endmills, disc cutters, long-edge or helical cutters, and side mills and facemills.

When machining a slot that starts and ends open, for instance, Tucker recommends an indexable-insert disc cutter.

"You are not stopping in the part," he said, "and 99% of the time a wheel cutter is more productive because you have more inserts in the cut than an indexable or solid-carbide endmill."

Pollock said the DOC determines the type of tool to apply, with a facemill limited to the DOC capability based on insert size.

"If you need something more than that," he said, "you need to use a helical mill that has multiple inserts than can make up the cutting edge depth. A helical tool has a long cutting edge; some call it a porcupine cutter."

Greenleaf designs cutters that go into curved shapes, such as the airfoil of a blisk. Image courtesy of Greenleaf

In addition, a workpiece material influences the geometric features of a tool. Bronson said stringier materials, such as some high-temperature superalloys, require a tool with a positive geometry to more effectively shear the materials. He said a positive geometry also is recommended for cutting titanium and aluminum alloys.

On the flip side, he said a negative geometry is more appropriate for abrasive materials like cast iron.

"It gives you a little bit stronger edge and reduces edge breakdown," Bronson said.

To help minimize edge chipping on positive tools, they typically have a small hone on the edge that measures from 0.0127 to 0.0254 mm (0.0005" to 0.001"), depending on the workpiece material and application, he said.

For severe slotting operations where trouble with vibration or edge chipping might occur, DeRoss suggests a heavy edge preparation.

"It might be positive," he said, "but at the edge, there might be a little flat to help give it more strength."

DeRoss said a highly positive edge usually reduces vibration while creating curled, manageable chips, but the more positive the edge, the weaker it becomes.

"You always want to push that limit but not to where you give up the edge strength," he said.

Pollock concurred that an edge that's too positive poses pitfalls.

"Particularly in soft materials," he said, "it might have a tendency for the material to try and pull the cutter into it and pull it off its line of center. That can induce a lot of chatter."

In addition to an edge preparation, DeRoss said applying a chemical vapor deposition coating strengthens the cutting edge of an insert, though the edge won't be as sharp as one with a physical vapor deposition coating.

Indexable-insert wheel cutters with internal coolant, such as the CoroMill QD tool, are effective for groove milling. Image courtesy Sandvik Coromant

Tucker said that about a year ago Sandvik Coromant introduced Inveio coating technology, which further improves the ability to prevent cracks from forming on the edge line.

"It has a columnar structure," he said. "The better those columnar structures are aligned, the better the ability to stop crack propagation in the milling process."

Cool Cutting

To help with chip control for solid-carbide slotting tools, Pollock recommends using a chip splitter on the cutting edge.

"So instead of taking a deep depth of cut and long chips in the axial direction," he said, "with chip splitters along the cutting edge, you get short chips in the axial direction."

Rather than coolant, Pollock said he prefers chip splitters to aid chip evacuation, if possible. In addition, he discourages using high-pressure coolant, which generally requires a pressure of 69 bar (1,000 psi) or higher.

"I almost never want to use that type of coolant system with milling because it can induce so much vibration into the application," he said.

Although Tucker typically recommends high-pressure, through-tool coolant, he said too much coolant pressure in a cutter creates vibration, especially when slotting or grooving aluminum at high speeds and feeds.

"You can get a vortex situation inside a groove where the pressure is so great that the cutter starts vibrating," he said. "There is a fine line there, but it's usually a condition of how fast you are spinning that cutter."

Bronson said flood coolant is more beneficial than high-pressure coolant when slotting to control the temperature of a part and keeps its dimensional criteria stable.

"It's very unusual for us to see 1,000-to-1,500-psi applications in indexable slotting," he said.

Using an air blast or chilled air is another option for keeping a part and tool cool when slotting. Bronson said an air blast or chilled air is recommended for slotting with ceramic inserts, which Greenleaf has a long tradition of producing. Air cools a part and tool and helps remove chips from a toolpath, extending tool life. In addition to uncoated ceramic inserts, the toolmaker offers coated ones, which resist heat, can increase lubricity and add a thermal layer to prevent chemical erosion when machining.

As recently as five years ago, ceramics were considered a niche area limited to the types of materials they could cut effectively, such as silicon nitride for cast iron and whisker-reinforced ceramics for high-temperature superalloys and hardened materials. He said that changed with Greenleaf's introduction of its Xsytin-1 multipurpose ceramic grade, which is suitable for machining cast and ductile iron, high-temperature alloys, steel, stainless steel and other challenging-to-machine metals.

A Suitable Approach

There are three basic slot milling techniques: conventional, plunge and trochoidal, or dynamic.

With conventional slot milling, Pollock said the tool runs straight through in an x-to-y move and takes a full WOC.

An example of a slotting cutter is shown. Image courtesy of Greenleaf

"You are a little bit limited in the number of teeth you can use because you need more flute space," he said, "so the material that you are removing has to fit into that flute space and be evacuated."

Pollock said another limitation is the feed per tooth and cutting speed that the tool can run at based on the rigidity of the machine and how much force the tool can withstand before fracturing.

Plunge milling is a problem-solver in vibration-sensitive applications, such as those with long tool overhangs, when deep slotting and when a weak setup can't be overcome, Sandvik Coromant reports. However, plunging provides a low level of productivity under stable conditions and requires a rest milling or finishing operation, and the selection of suitable tools is limited.

Pollock said when dynamic slot milling, the cutter takes smaller, lighter and faster cuts than when conventional slotting and usually is performed on highly agile machines with smaller spindle connections than are found on the massive machines used for conventional approaches.

"We are definitely seeing a trend in that direction for increasing the metal removal rate," he said.

Tucker said older machines, however, may not be capable of taking a big length of cut with light step-overs that dynamic slotting requires.

"We are always going to recommend solutions based on productivity," he said. "In order to get that productivity, you have to use some of these light and fast approaches."

Of course, end users typically balk at investing in a new machine tool to boost the productivity of a cutting tool when the current machine isn't broken, but a cutter might enable a lower capital investment when one already is planned. Bronson recalled a customer that was taking at least 30 minutes to conventionally produce a slot and was expecting to purchase 100 machines over a two-to-three-year period because of the customer's high-volume requirements. After Greenleaf designed a cutter to increase the removal rate and complete the same operation in about four minutes, the customer then needed to purchase significantly fewer machines.

Pollock said although virtually every part manufacturer has at least someone at the shop who's familiar with dynamic milling, some people resist change and it can be challenging to convince everyone to go in that direction.

"If you have been at this for 20 years," he said, "it's kind of hard to get your head around it and that you can actually machine a material that fast."

For more information about slot milling, view a video presentation by Sandvik Coromant at www.ctemag.com by scanning the QR code on your smartphone or entering this URL on your web browser: cteplus.delivr.com/2an3a